by Marie Petersmann and Anna Berti Suman

Read Part I, published on June 30th

Citizen Sensing: From Sensing Radiations to COVID-19

In the immediate aftermath of the disastrous earthquake and tsunami that struck eastern Japan on 11 March 2011 and the subsequent meltdown of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, accurate and trustworthy radiation information was publicly unavailable.

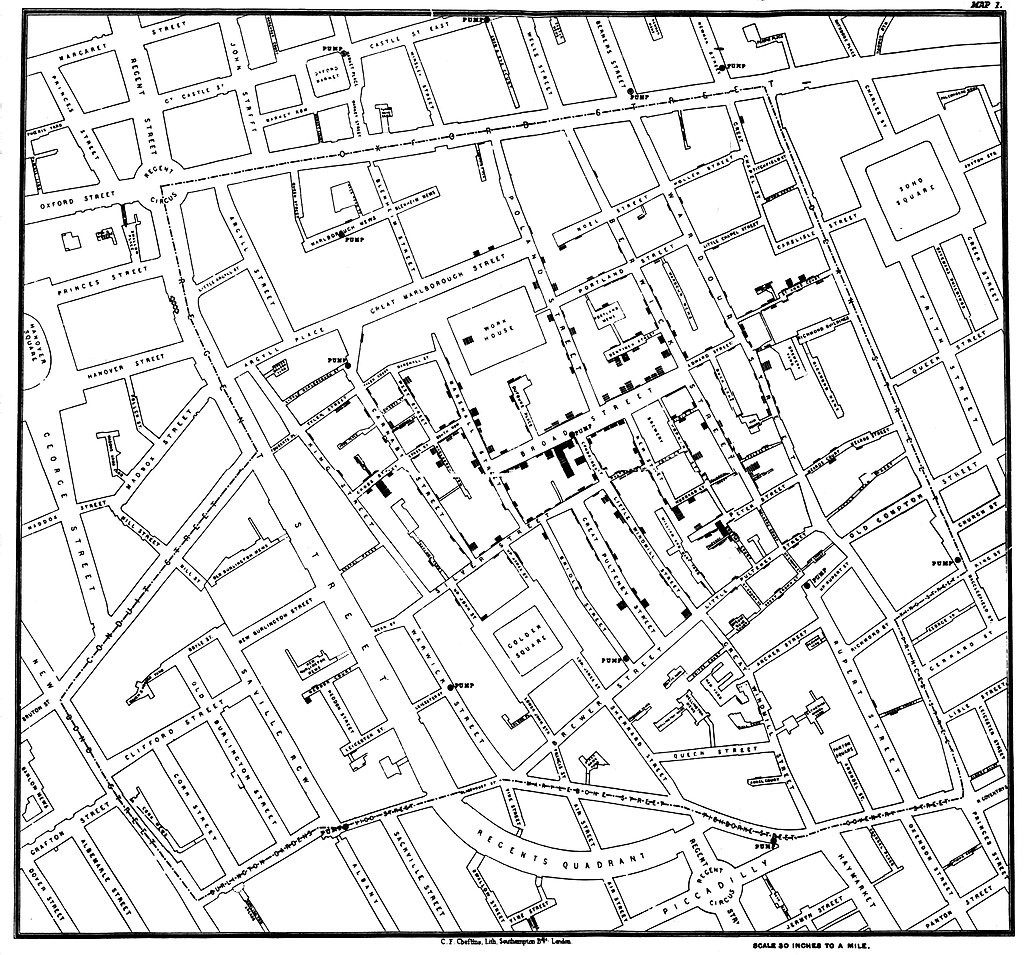

Against this backdrop, a volunteer-driven non-profit organization called Safecast was formed to enable individuals ‘to monitor, collect and openly share radiation measurements’ and other data on radiation levels. The initiative ‘mobilized individuals and collectives’ in response to risks that were perceived as extremely urgent to monitor, namely the post-Fukushima radiations burdens. Safecast can thus be regarded as a ‘shock-driven’ initiative that constitutes a ‘successful [example of] citizen [sensing] for radiation measurement and communication after Fukushima’. As this initiative grew quickly in size, scope and geographical reach, Safecast’s mission soon expanded to provide citizens worldwide with the necessary tools they need to inform themselves by gathering and sharing accurate environmental data in an open and participatory fashion. Through a form of ‘auto-empowerment’, Safecast participants were able to monitor their own homes and environments, thereby ‘free[ing] themselves of dependence on government and other institutions for this kind of essential information’. As described on Safecast’s website, this process gave rise to ‘technically competent citizen science efforts worldwide’.

Reaction

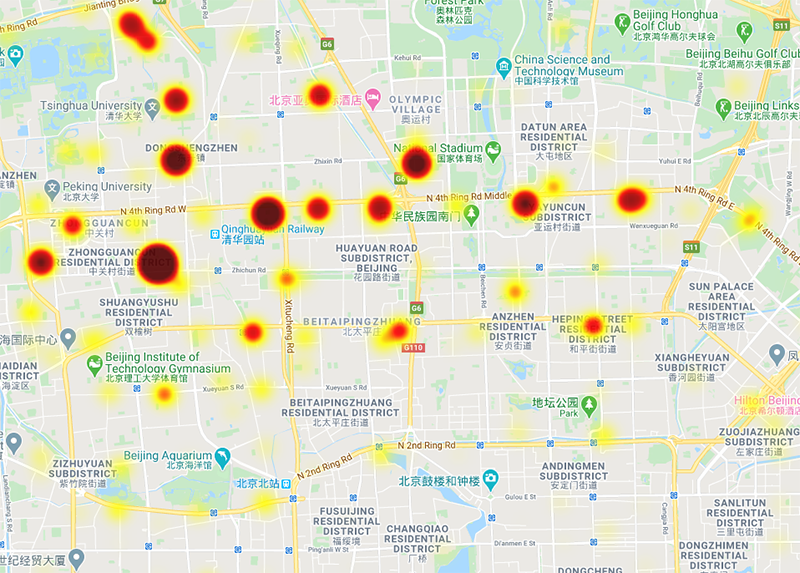

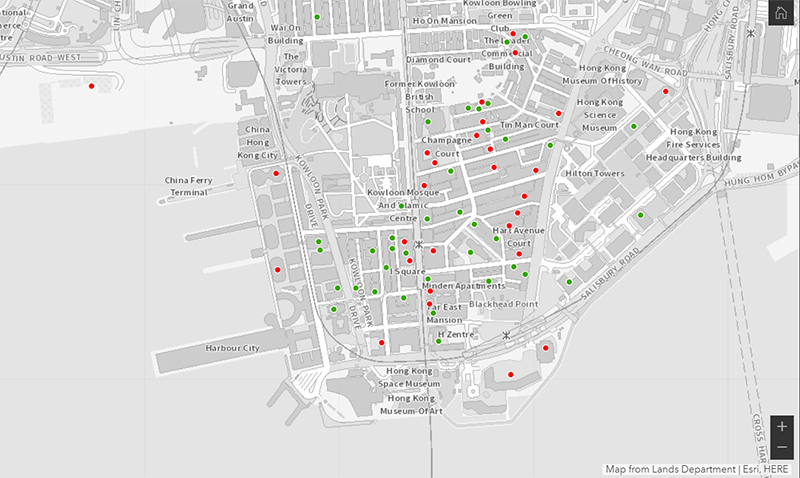

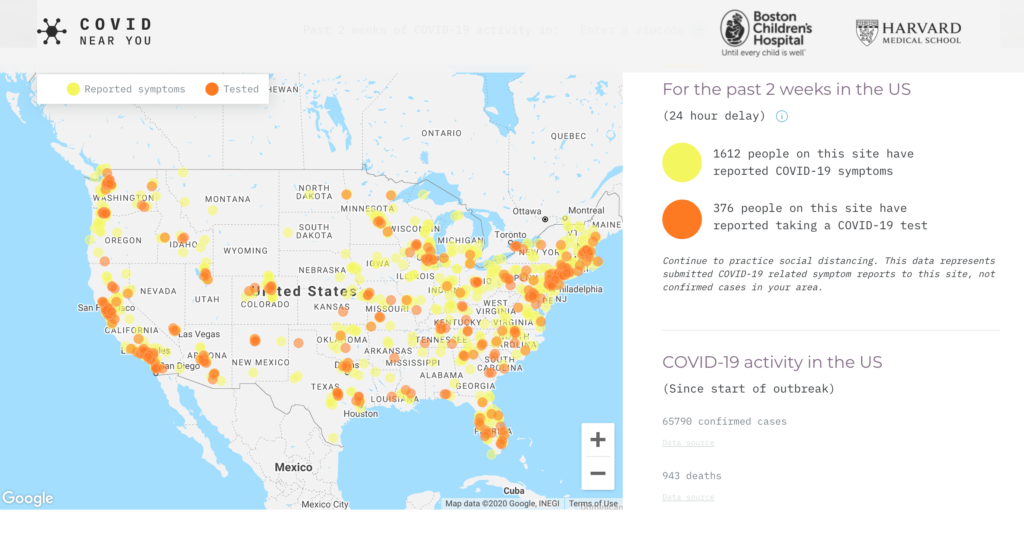

Following the outbreak of COVID-19, the Safecast collective engaged in a rapid response to the virus by setting up an information platform on the evolution of the crisis and a map of COVID-19 testing that provides a picture of where to obtain testing options in various locations (see covid19map.safecast.org). Over the years, Safecast had accumulated much experience and insights on ‘trust, crisis communication, public perception, and what happens when people feel threatened by a lack of reliable information’. Yet, the Safecast collective still struggles to be heard as ‘many scientists ignore their data’. Despite this scarce official recognition, Safecast took advantage of its experience and societal impact to rapidly respond to the current pandemic.

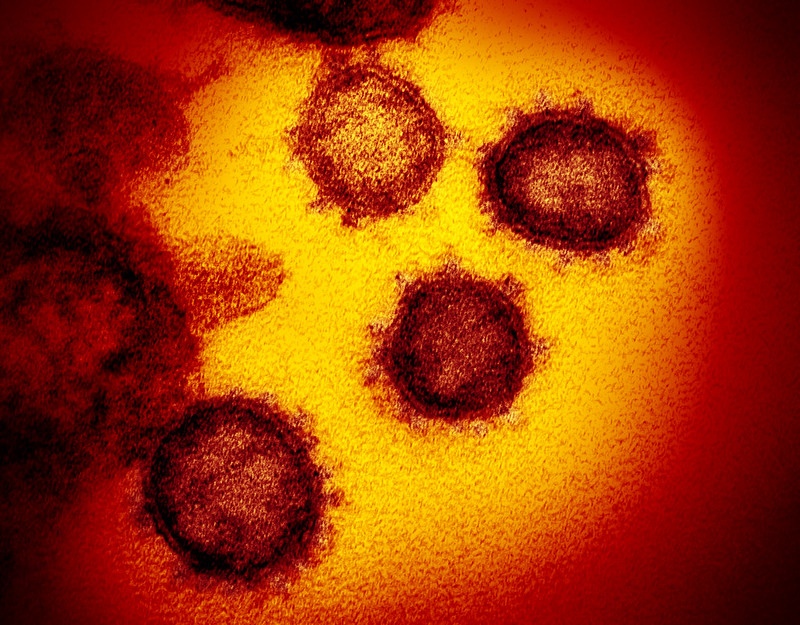

As observed by Safecast volunteers, ‘[w]e find ourselves again trying to better understand what is happening’. In a webinar on ‘Lessons we are learning from the COVID-19 pandemic for radiological risk communication’, Azby Brown (as volunteer at Safecast and director of the Kanazawa Institute of Technology’s Future Design Institute in Tokyo) drew several links between the nature of ionising radiations and the COVID-19. By alluding to the invisible presence and constant risks posed by such hyperobjects, the invitation to the webinar started by highlighting that ‘[y]ou can’t see, smell, or taste it, but it may be a problem’, which applies equally to radiations as well as viruses. Elsewhere, Brown observed that:

Fear of the unknown is normal, and radiation and viruses are both invisible threats that heighten anxiety. Most people have almost no way to determine for themselves whether they have come into contact with either of these threats, and they find themselves dependent on specialists, testing devices, and government and media reports. If the government and media do not provide clear, credible explanations and prompt communications, misinformation and mistrust can easily take root and spread.

For Brown, Safecast could provide a relevant risk communication perspective in the current COVID-19 context based on the experience gained after the Fukushima disaster. Despite major differences between ionising radiations and COVID-19, similarities in risks communications are worth exploring.

Analogous governmental failures on risk communication were observed regarding, for example, shortcomings in rapidly conveying clear messages to the public and communicate strategies based on non-conflicting expert and policy opinions. The ambiguous and incomplete information received from the authorities generated a sense of uncertainty and distrust for many citizens dependent on single sources of official information. Against this backdrop, initiatives such as Safecast that enable people to control and monitor the presence and degrees of certain risks provide an alternative source of credible crowdsourced information. Beyond the immediate informational benefit for sensing citizens, such tools can further enable holding governments and officials into account.

A global phenomenon

At the time of writing, citizen sensing initiatives tackling COVID-19 are multiplying around the world (as listed here and here or exemplified here). Such citizen sensing practices ‘constitute ways of expressing care about environments, communities and individual and public health’ (Gabrys, at 175). As argued by Gabrys, these practices ‘are not just ways of documenting the presence of [threats]’ but are also ‘techniques for tuning sensation and feeling environments through different experiential registers’ (Ibid, 177). Granular monitoring by sensing citizens is seen as particularly valuable in times of emergencies, when governments are faced with urgent, massive and systemic risks of spatial and temporal scales that defy immediate control – such as the current pandemic.

Civic ‘sentries’ can both offer relief to affected people through solidarity networks and provide resources to policy-makers and scientists through wider access to grassroots-driven and situated information ‘from below’. Citizen sensing initiatives also enable lay people, turned into ‘sensing citizens’, to retain a greater degree of agency over the production and use of the data assembled. Against the ever-increasing rise of ‘bio-surveillance states’ and the development of ‘symptoms-tracking’ and ‘contact-tracing’ apps, ‘bottom-up innovations’ might help to counter the acceleration of ‘digital surveillance’ that may be hard to scale back after the pandemic.

Open access citizens’ sensed data may be considered more transparent and trustworthy by the public and convey important information on widely shared everyday lived experiences. By rendering data about real but invisible threats (and how these are perceived and felt) available through the intermediary of sensing citizens, a redistribution of (access to) information and agency in knowledge production is enabled. Finally, the increased ‘(datafied) relational awareness’ and ‘forms of correlational sight’ (Chandler, at 130) that are produced can create new appreciations of inherent yet invisible connections between human and non-human coexisting lifeforms.

Concluding thoughts

As hyper-objects, both the COVID-19 and climate change defy not only our understanding but also our control. Their causes and effects are so massively dispersed across space and time that they evade unmediated appearance. The impacts of hyperobjects operate through forms of ‘slow violence’, which are ‘often attritional, disguised, and temporally latent, making the articulation of slow violence a representational challenge’ (Davies, at 2). Only partial, local and deferred manifestations can be captured through experience. Our way of relating and responding to such hyperobjects depends on temporal, spatial and emotional predicaments. The more temporally immediate, spatially proximate and emotionally tangible the threats of hyperobjects are, the greater and quicker our responses tend to be. Temporal, spatial and emotional scales are central to our ability to sense the presence of invisible threats such as viruses and changes in the climate.

While socio-ecological threats posed by climate change have been present for decades and increasingly materialized across the globe in recent years (for certain peoples more than others), responses remained relatively marginal in light of the risks at stake. Conversely, while the (health) threats posed by the COVID-19 are of a relatively shorter-term (leaving aside the longer-term consequences of the socio-economic crisis it engendered), those risks triggered immediate and radical responses. The fact that the COVID-19 is sensed as a ‘direct risk’ to individuals or vulnerable relatives prompts instant reactions. The sensed proximity (both temporal and spatial) of the invisible threat points to important questions.

The current pandemic brought to light what climate activists deplored for long, namely that we tend to care more for risks posed to our individual conditions. A sense of emotional distance is generated by spatial and temporal gaps. This self-centred sentiment is reinforced by an anthropocentric appraisal that limits our ethics of care to the sole concern for the human species, instead of striving to ‘support the flourishing of other animals and natural things’ with which we are intrinsically entangled. While pessimistic projections on climate change have often been framed as triggering a sense of denial, paralysis or aporia, the current pandemic shows how emotions such as fear, anxiety and dread can also lead to mobilization, collective concern and action.

Emotions are, ultimately, about social movement, stirring and agitation: the root of the word ‘emotion’ is the Latin emovere, which implies both movement and agitation. Despite serious risks of strategic exploitation of fear or despair by political actors instrumentalizing a ‘state of exception’, such emotions can also unleash an enhanced sense of solidarity and cohesion through increased awareness of our fragile state of coexistence and new forms of collective attachment. This is true at the human level – as we saw emerging a myriad of new forms of ‘social proximity’ – but also at a ‘more-than-human’ level, by inviting to be alert and attentive to ‘humans’ impact on and interdependence with the ‘natural’ world we are part of. Such sensibilities can give rise to a sense of cross-species shared vulnerability, where hope and grief enable to re-envision different forms of ‘collaborative survival’ (Tsing, at 4). In this short blogpost, we did not tackle any of these ethical questions in depth.

More modestly, we explored how citizen sensing initiatives can help bridging the temporal, spatial and emotional distance between human (re)actions and present, yet invisible, threats through self-production of independent knowledge and agency. As Gabrys reminds us:

These practices are not just ways to rework the data and evidence that might be brought to bear on environmental problems. They are also ways of creating sensing entities, relations, and politics, which come together through particular ways of making sense of environmental problems (Gabrys, at 732).

We argued that, by recasting the actants and subjectivities involved, the technological and data-based sensors used by ‘sensing citizens’ have a world-making effect by facilitating awareness and intelligibility of certain threats. While physical isolation is being implemented (almost) globally, this doesn’t mean that we need to feel isolated and powerless. Daily citizen science is all about re-imagining scales and the potential of working together to provide a sense of connection and purpose. In reconfiguring the ‘distribution of the sensible’ – as a ‘system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it’ (Rancière, at 12) – new avenues are opened up for citizens to foresee, understand and visualize threats, and ‘(ac)count’ the damages caused (Bettini et al., at 6 and 8).

Beyond the realm of immediate perception and individual or collective (re)actions, decentralized, grassroots-driven and cooperative sensing technologies may also redistribute agency to challenge more ‘official’ monitoring infrastructures and hold actors into account to galvanize appropriate political responses. Politics, ultimately, ‘revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time’ (Rancière, at 13). These configurations of the sensible, we argue, provide an important terrain for rethinking the politics of hyperobjects such as the COVID-19 and climate change.

About the authors

Marie Petersmann is postdoctoral Research Fellow (Swiss National Science Foundation) based at the Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development, Utrecht University. Anna Berti Suman is NWO Rubicon postdoctoral researcher at the Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society, seconded at the European Commission Joint Research Center (JRC) – Digital Economy Unit.