What does it mean, in everyday life, to experience the first pandemic in a datafied society? This article takes a data perspective to discuss the specificities of the Italian experience of the COVID-19 crisis.

by Tiziano Bonini

Forms of datafication of society during the COVID-19 pandemic have varied from country to country. The biggest concerns relating to datafication of citizens were the spread of contact tracing and notification apps and the risks these would bring to citizens’ privacy. Some suggest that people have become passively accustomed to surveillance by private multinational companies (surveillance capitalism, Zuboff 2019) but are reluctant to agree to be monitored by their country’s Ministry of Health.

In Italy, as in many other countries, many controversies have arisen around health tracking apps. In the end, the Italian app – Immuni – was released on June 2 and in 8 days it was downloaded by two million Italian citizens. While this might seem a success story, things are more complicated than that. Experts pointed out that it will need at least 30 million downloads to make the app useful for contact tracing and there are many doubts about the possibility of reaching these numbers, also because many smartphone models do not support it (as for example all iPhone models before 6s).

Debate on the Immuni app has revealed the existence of two opposing fronts: we can refer to them as the techno-solutionists on the one hand, and the techno-apocalyptics on the other. The former believe they can slow down the diffusion of contagion simply by having an app installed on their mobile phones; the latter instead reject any form of surveillance, except that coming from Facebook or Google. Yet, the importance of data during the pandemic did not emerge only during the debate on Immuni – public narrative of the lockdown period was in many ways crossed by the rhetoric of dataism, meant as a blind and unconditional trust in data.

Every evening, at 6.30 p.m., for two months, the head of the Italian Civil Protection went on television to “give numbers” about the pandemic: new healed, new contagions, new hospitalized, new deaths compared to the previous day. Despite the dubious reliability of those data (the dead, it was later discovered, were many more; the contagions were ten times as many, and Italian regions did not provide data in a homogeneous way), this press conference immediately turned into a collective ritual, an appointment not to be missed, like President Roosevelt’s fireside chats on the radio, a real “media event” (Dayan & Katz 1992): the (macabre) Pandemic Ceremony. This national ceremony was flanked, in scattered order, by other media micro-cerimonies on a local or municipal basis: this refers to the live-shows on Facebook, You Tube and Instagram of dozens of Italian mayors, who, inspired by the macabre national ceremony, every night “entertained” their fellow citizens telling about the state of the virus spread in their municipality through use of data. In this case data were employed as objective and neutral facts to convince citizens to stay at home and “flatten the curve”.

But if we stopped here, we would end up seeing only a part of the story, the one in which data were used to build a public narrative passively accepted by citizens. That’s not the case, or at least it wasn’t for everyone. Since the early days of the pandemic and lockdown, organized groups of citizens have confronted available data trying to analyze them together, drawing different conclusions from the official narrative or even producing new data. Many have opened Excel spreadsheets where they could download Civil Protection data (made available as Open Data) to try to interpret them independently.

Many others have created Facebook groups to discuss such data and their meaning. Some turned to their math friend, some dusted off their old statistical knowledge, others simply followed the home made analysis of their Facebook friends. From this point of view, we could say that lockdown represented a period of collective learning about the role of data in society and accelerated the emergence or spread of data activism, data journalism and open science practices.

On the side of data journalism, the local newspaper L’Eco di Bergamo made an important investigative work. By collecting data independently and examining those already available, it showed that the number of deaths in the province of Bergamo, one of the most affected cities in Italy by Covid-19, was almost double the official number.

On the side of data journalism, the local newspaper L’Eco di Bergamo made an important investigative work. By collecting data independently and examining those already available, it showed that the number of deaths in the province of Bergamo, one of the most affected cities in Italy by Covid-19, was almost double the official number.

On the open science and citizen science side, one of the most active groups on the examination, interpretation and sharing of data on the evolution of the pandemic in Italy was the Facebook group Dataninja, a community of journalists, citizens and researchers created in 2012 by a group of Italian journalists interested in the use of data in creating information. This community, which counts more than 3,000 members, for two months produced a large amount of data, “home made” graphs and tables, representing a collective effort to try to make sense of what was happening.

Still on the open science side, within the community of medical doctors other interesting projects related to data have emerged, such as the Giotto Movement in Modena, created by an association of young Italian family doctors with the aim of building together an electronic register (a shared excel sheet) where to collect in one place all those COVID-19 suspect patients that didn’t match the official criteria to be eligible for a COVID-19 test and taken care of by the Public Health and Hygiene Service. This need was felt by several family doctors, who, simultaneously and without consulting each other, created very similar “low technology” tools (Excel or Word sheets) to keep the situation under control. These were the first weeks of emergency and the situation on the ground was very chaotic. The project was developed in three main phases:

- Consultation among young doctors from various Italian regions (thanks to the network of the Giotto Movement, an association of young doctors) to define a first version of the register,

- A group of about 20 couples of doctors in training in General Medicine tested the instrument for a week and at the end of this week, after a mutual comparison on strengths and weaknesses, they built the final version of the register,

- Diffusion of the register to all family doctors, thanks to the collaboration of the Primary Care Managers of Modena, and to colleagues from all over Italy thanks to the network of doctors of the Giotto Movement who contributed to its realization.

On the side of data activism, the NGO Action Aid, since March 12, has activated a national mapping of spontaneous and institutional solidarity initiatives (such as volunteers to do shopping for the elderly in various cities), those of psychological support, fundraising, debunking fake news and dissemination of scientific data. The project is named Covid19Italia Help and consists of an interactive map in which anyone can report and insert solidarity initiatives going on the Italian territory. The creators of the project described it as a civic hacking initiative and the idea (and also a good part of the project) came from the same team that had developed the EarthQuakeCentroItalia project, a very similar civic hacking initiative that consisted of a collective effort of managing the emergence caused by the Eartquake that struck Central Italy in 2016 through the use of open data and citizen generated data.

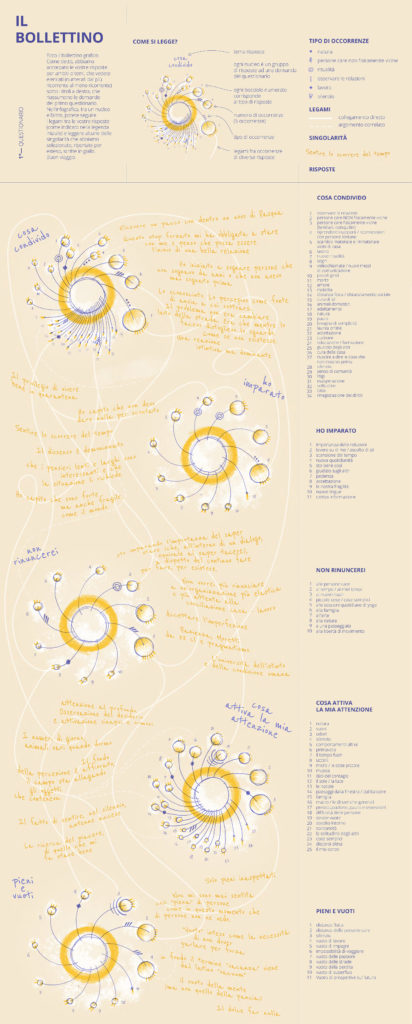

In Bologna, Kilowatt – a working cooperative made up of different souls working in the fields of social innovation, circular economy, communication and urban regeneration, has launched the project “Passa il tempo, passa la bufera” an experiment in domestic ethnography “at a distance”, to stimulate a ritual of collective self-observation. Kilowatt collected qualitative data through online questionnaires with open-ended questions, renewed once a week for five weeks. Respondents (583 people) provided very detailed accounts of their lives during lockdown, changes in their moods and their new domestic occupations. Data collected were then translated into info-graphics and collective diaries, which gave a collective portrait of the domestic climate during the pandemic. Kilowatt’s aim was to try to keep the pulse of what was happening in our homes and in our lives, accompanying us to a new normality, going beyond the logic of statistics and using the tools of ethnography”.

I talked via email with two of the creators of the project, Anna Romani and Gaspare Caliri. They told me that the answers to the last questionnaire clearly confirmed, at the same time, both the need of others and the need for solitude, as two indivisible and both necessary feelings during the lockdown. They also noticed the fear of the respondents that nothing will change: “we often hear this, but especially in relation not only to macro issues, but also to the individual management of one’s own days, after having discovered the special texture of slow, freed time, time to lose, time for idleness, time for oneself, time for loved ones…”. According to Caliri, “the instrument of domestic ethnography worked as a detector of the so-called warm data, the Bateson Institute would say, i.e. those relational data that give meaning (intelligibility) to a complex system and the possibility of collective learning: those data where the important thing is the connection, not the point”. In other words, domestic ethnography has been employed has a “technology of the self” (Foucault 1988): the activity of taking care of oneself during lockdown went through individual generation and collective analysis of qualitative data (the diaries).

These examples are only the surface of a process of domestication of data within daily life during the pandemic and are significant because they show, at least by some social formations, the ability and willingness to exercise agency with respect to data produced by institutions and narrated by the media. These examples show the need to negotiate, appropriate, decode, rework data coming from above and produce, in some cases, new meanings of data.

The collective process of knowledge production around the virus has been largely based on the capacity of sharing and interpreting data, but what I wanted to show here is that many private and collective initiatives from civil society have taken away, at least in part, the monopoly of production, analysis and verification of data by institutions. Moreover, these examples also provide evidence that not all social formations have adhered to blind faith in data and technology as a solution to the COVID-19 crisis.

About the author

Tiziano Bonini is associate professor in Sociology of Media and Culture at the Department of Social, Political and Cognitive Sciences at the University of Siena, Italy. He teaches Sociology of Communication (MA), Mass Media, Digital Culture and Society (BA) and Big Data and Society (BA). His research interests include political economy of the media, platform studies, media production studies, and digital cultures.