COVID-19, an epidemic that emerged in Wuhan city, has been always entangled with information censorship since the very beginning of it being detected in China. The Internet has witnessed a battle between censorship towards criticism and investigative reports, as well as supported various forms of resistance such as organizing group-documentation on GitHub and creating alternative new media projects. In this crisis, we see how citizens, journalists, and activists are brought together by digital networked communication to fight for the rights to be informed with accurate information.

by Anonymous Contributor

COVID-19, an epidemic that emerged in Wuhan city, has been always entangled with information censorship since the very beginning of it being detected. During the last week of December 2019, doctors in Wuhan, including Dr Li Wenliang who became known as the virus whistleblower, used their personal social media accounts to sound the alarm about the rapid spread of the unknown disease. Their attempt was stigmatised by local authorities as “spreading rumours and misinformation”. This is why even at the times of COVID-19 the Chinese internet witnesses a battle between censorship and various forms of resistance whereby Chinese citizens and journalists deal with the censored content and fight for the rights to be informed with accurate information by using digital networked communication. This creates a temporal “us” against the authorities state.

Nick Couldry offers a critical reflection on the ways in which digital networked communication forms solidarity——what he termed as “the myth of us” (2014). He argues that timescale matters as one of the social conditions of political changes, because networked action has provided effective means for disrupting government surveillance and the accessibility accounts for quick and massive mobilization. Yet, the long-term contexts that guarantee sustainable individual action in and through networks are missing. The author also says that it is too early to conclude that digital networks function as a process of autonomous communication. Nonetheless, Couldry does not deny the potential of political change that the use of digital networks in recent social movements might give rise. We can think of how COVID-19 outlined and amplified the problems of internet censorship in China, which triggers various ways of resistance that could become legacies for activists and citizens even after the crisis.

GitHub: A new frontier of data activism

The individual and collective documentation of COVID-19 reports on the software repository GitHub reveal a form of data activism as a novel frontier of media activism, as Milan argues (2017). It is a re-active action enacted by technological experts who used web crawling or other data collection processes to transfer the related reports and published articles published to the repositories, racing against the speed of the censorship.

“Terminus2049”, an online crowd-sourcing project relying on GitHub, was set up in 2018 to archive articles that were censored from mainstream media outlets and social media such as WeChat and Weibo. As stated in its GitHub page, the project’s slogan is “no more 404”, where 404 is the error code indicating that a server could not find the requested page. It functions as a site of resistance towards the state censorship on media content. During the outbreak of COVID-19 in China, Terminus2049 also archived and documented various reports and articles that had been censored or removed, including a serious of in-depth reports questioning Wuhan local government’s early-stage reaction to the coronavirus published by Caixin Media. On the 19th of April, three volunteers from Terminus2049 went missing in Beijing and were presumed to be detained by the authority. However, Terminus2049 is not the only project on GitHub that is involved in crowdsourcing documentation of coronavirus memories. Similar projects such as “2019ncovmemory” (which has already set their archive to private to avoid risks),“womenincov” (which features recordings of female medical staff and issues related to domestic violence), and “workerundervirus” can be also found on GitHub.

How does GitHub become a platform for Chinese citizens and activists to preserve counter-narratives and to make sense of the accountability and legitimation of the government? To begin with, the software development website GitHub is accessible in China for its function of code-sharing. The platform gained its visibility outside the developer communities because of the Anti-996 Movement in 2019, initiated by Chinese programmers to protest again the excessive working conditions in tech companies. As part of the movement, the “996.ICU” project was devoted to complying a list of companies that follows a 996-working schedule (from 9 am to 9 pm, 6 days a week) and its repository has quickly become one of GitHub’s fastest-growing repositories. After mainstream media’s reporting and the wide-spread discussion about 996-working culture in China, the movement has brought people’s attention to GitHub itself as a suitable site for civic participation and a tactical choice for organizing contemporary activism in China, given its capacity to be operated both within and beyond “the Great Firewall”.

The explosion of creativities on social media

Yet, I am not arguing that GitHub is the only online space to contain Chinese citizens’ memories of coronavirus and their strong demand for transparency and accountability. In fact, social media accelerates cycles of action and protest and have the ability to produce new forms of collectivity.

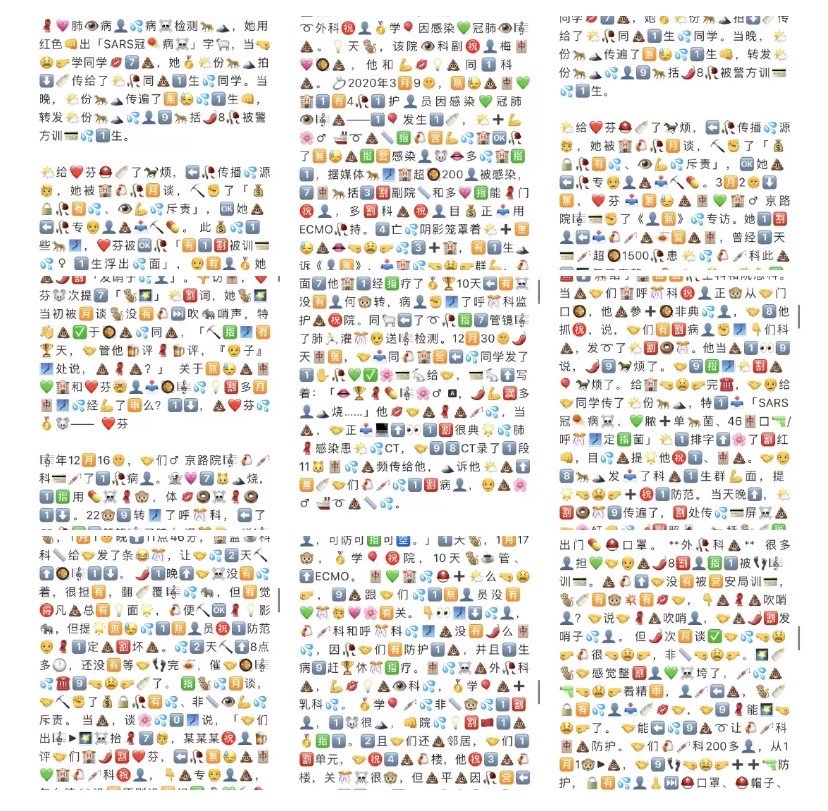

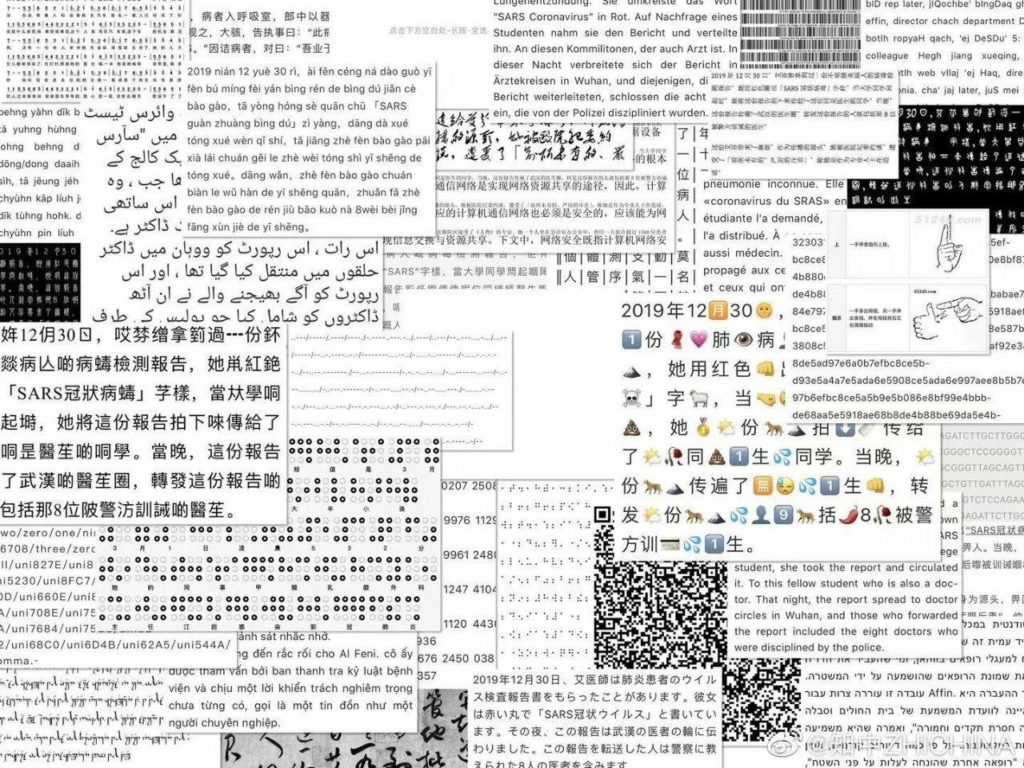

What amazed me the most is how citizens creatively and collectively express their anger, discontentment, and solidary in spreading an interview of Dr Ai Fen on social media platforms. On 10th March, Renwu Magazine published an article titled “The one who gave out the whistle (发哨子的人)”—an interview with the head of Emergency Department in Wuhan Central Hospital, Dr Ai Fen, featuring her allegations that she had been reprimanded by superior officials after attempting to warn her colleagues on the novel virus and her experiences in the emergency department for the past two months. The article was quickly removed. However, censorship failed to silence the public. Citizens have started their own ways of preserving and spreading the article: from screenshots, replacing words with emojis, and formatting the article vertically instead of horizontally, to more creatively using a serious of QR codes, using fictional languages such as Klingon and Sindarin, using Morse code and computer science encoding system Base 64. Chinese social media platforms were turned into battlefields against the censorship. As communication scholar Kecheng Fang commented to BBC, it was a ceremonial event that connected individual citizens who share similar values and led to the formation of solidarity.

Alternative/Artistic new media projects

The creativities in this event bring forth the possibilities of adapting alternative or artistic activism, which is often recognized by its ability to slip under the radar and not be identified as “politics” to authorities, while still being able to communicate a social message. As Leah Lievrouw points out, besides citizens’ active engagement in spreading censored content regarding coronavirus on social media platforms, activists have incorporated the concept of memories into creating alternative and activist new media projects.

“Unfinished Farewell” is a new media project that offers a pace for people to release their grief and for the public to mourn, directed by visual designer Jiabao Li and Laobai Wu. By collecting help-seeking posts and heartbreaking stories of losing the loved ones from accounts on different social media platforms, the project addresses individual stories to form counter-hegemonic narratives. It invites the visitors to reflect on a question: “after this pandemic, who can remember the pain of someone like my mother who had nowhere to seek medical treatment, being refused by the hospital, and died at home?” There is a need to document similar tragedies as evidence in terms of seeking accountability after the crisis, and this project set the urgency for such a need in an emotionally powerful way of presenting the visualization of information of the lost lives.

“Qingming, A Sculpture of Resilience” has appeared online. Qingming Festival, which is also known as Tomb-sweeping Day, is a day to mourn and commemorate ancestors and the lost loved ones. Because of the pandemic measurements, people in China were unable to visit graves in this year’s Qingming Festival and online tomb-sweeping applications were used as an alternative. However, the project is not created for tomb-sweeping. It invites you to virtually join a counter-clockwise walk in front of the Hongshan Auditorium in Wuhan. It aims to transform the trajectories left by visitors into an online monument, which represents a collective will of remembering how the officials were trying to silence the alarms on the existence of coronavirus in Wuhan, presumably related to making sure the success of holding the “Hubei Two Sessions” at Hongshan Auditorium. As strongly stated in the website, “We shall never forget our pain and tear. Neither should we stop examining the systematic problems exposed during the crisis, the strive for a better future”. Despite that the state’s regulations and the pandemic measurements prohibit citizens to gather physically in front of Hongshan Auditorium in Wuhan, the project records an artistic form of protest online.

The political environment and the strict monitor and censorship voluntarily conducted by corporated social media platforms in contemporary China hamper the possibilities for organizing physical protests or forming grassroots collectives. The COVID-19 crisis has triggered an intensity that lasts for months in everyday life, but it also nurtured creative and alternative ways of resistances that could go beyond the restriction of holding protests physically. Despite that fact that one should be cautious about not mistakenly assume that the forms of collectivity in the crisis can represent the whole social picture, I would like to believe the diverse forms of resistance towards censorship will be able to maintain and evolve into the future.