This article addresses the role of data in efforts to contain the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa. Drawing on multiple state examples, it discusses the ethical questions posed by datafied public health surveillance and the importance of harmonising national data protection systems.

By Oarabile Mudongo

COVID-19 presents a dynamic overtone of an African society encountering digital data transition in almost every aspect of human activity, from digital contact tracing to surveillance, all initiated by governments to help control the spread of COVID-19.

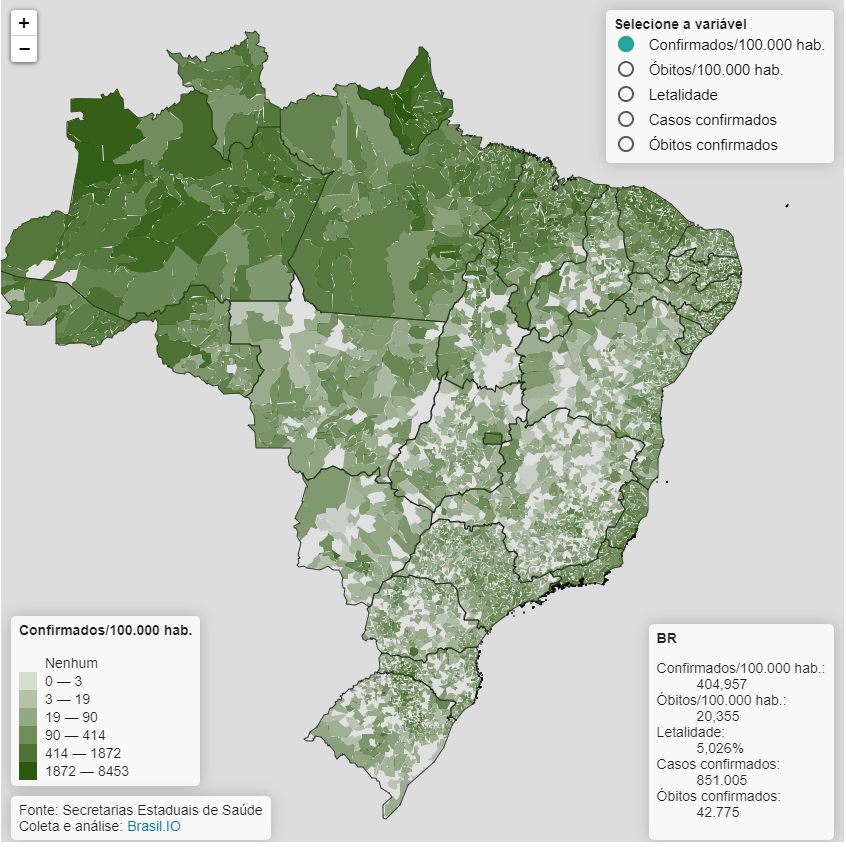

The number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 in Africa remains comparatively low, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) there are over 200,000 confirmed cases as of 1st June. However, these numbers are growing. A newly published report by the Partnership for Evidence Based Response to COVID-19 (PERC) exposes some of the alarming findings of the devastations of COVID-19 across Africa, with the head of WHO cautioning African states to prepare for the worst.

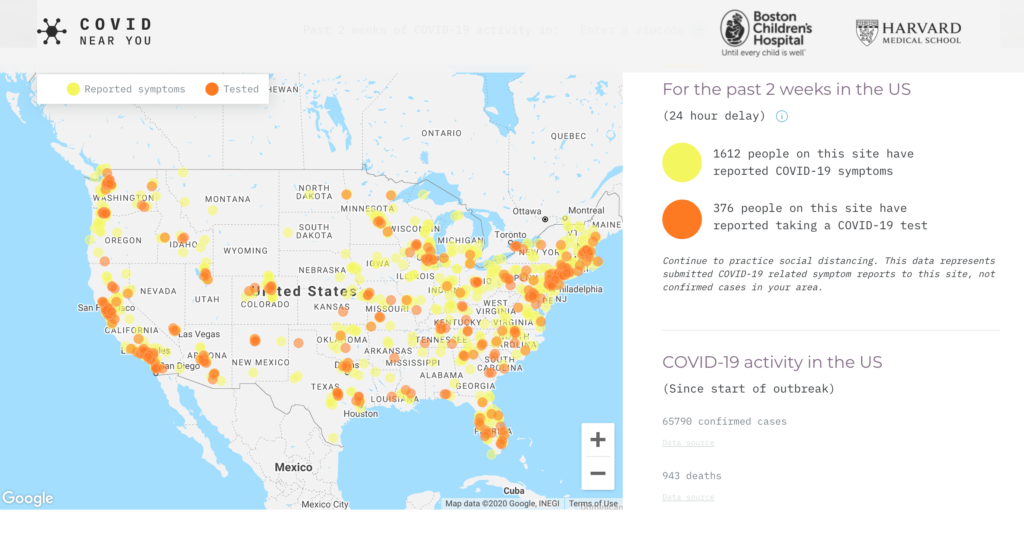

As African governments continue with their efforts to track people exposed to coronavirus and combat its spread, several countries in the continent have adopted various techniques such as digital contact tracing technologies (mobile apps using Bluetooth), data mining and sharing of aggregated geolocation data from mobile operators. In South Africa, for example, researchers at the University of Cape Town are developing a COVID-19 app to assist the government track COVID-19 positive cases, and also mobile operators are sharing phone location data about movements of people. While on the other hand, the government through a partnership with Telkom and Samsung alongside the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD) and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) are developing a novel track and trace system that identifies infected people.

Furthermore, the Botswana government has also announced a contact tracing app that centralizes people’s data in the government-owned database whereas in Kenya the state is surveilling mobile phones of individuals who are on self-quarantine and detaining those who contravene the restrictions imposed on movements. In general, it is still unclear which countries in Africa are utilizing technology-driven disease surveillance tools except for a few countries mentioned above. If ignored and remain unchallenged, this adopted measures and tools being used have the potential to fundamentally violate personal privacy and other human rights.

In addition, these measures are likely to exacerbate unlawful discrimination and may disproportionately cause harm to minority groups. For instance, Telkom and Samsung are reportedly in talks with SA authorities to track those with COVID-19. The South Korean technology company Samsung, which recently faced some questionable ethics problemson its AI surveillance technology is now proposing to develop a big data analysis tool for the government which claims to track the spread of COVID-19 by tracing people’s movements. The problem with some of these tools deployed is that they use obscure algorithms, which may influence biased decision-making and contribute to discrimination.

At the helm of a datafied society is the amount of digital footprints people leave behind while accessing the internet, from monitoring movements of people and state output to targeted advertising online and the digital contact tracing apps developed to track COVID-19. Though many people may not remember every place they’ve visited, governments have the capacity to use digital trails to fill in the missing information on COVID-19 infected patients’ activities. For instance, in South Africa the government is working with mobile operators that are sharing cellphone data to trace people’s movements in response to COVID-19 pandemic.

Although these may be well-intentioned efforts by African governments, some COVID-19 surveillance and data mining interventions have been implemented with limited oversight structures. In addition, this has sparked debates around the ethics and legality of disease surveillance, and WHO has developed guidelines on ethical issues in public health surveillance. These guidelines must be considered to assist policymakers and health practitioners navigate the ethical issues presented by public health surveillance.

While Africa’s data protection landscape is somewhat evolving, on a regional level, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) adopted a Supplementary Act on Personal Data Protection and in 2013, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) published a Model Data Protection Act. Additionally, in 2014, the African Union adopted the Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection (the Malabo Convention). These measures demonstrate and support the adoption of data protection laws in the continent. Despite the regional organizations’ efforts, the overall legislative framework is not fully harmonized.

Nevertheless, COVID-19 has continually revealed the existing lack of collaboration and communication amongst states, intergovernmental organisations and mobile operators about the role technology plays in shaping public policy during COVID-19 pandemic. This is a complex issue that has proven a disconnect between society and governments exacerbated with suspicions and mistrust. Going forward, African governments need to scrutinize these concerns while acknowledging extraordinary circumstances that require stakeholder engagement.

Surveillance or monitoring measures should adhere to national laws and be limited in their scope to fulfil the aim of public health protection. These measures should be established as temporary and be limited as required to meet the needs of the public health emergency, with safeguards to protect human rights and any misuse of technologies by either private corporations or governments who may use the data for unlawful purposes.

Human rights principles reinforce the effectiveness of global efforts to combat COVID-19, creating a balance between the right to health and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms is the best approach to fighting the pandemic. These principles are in fact intertwined. If human rights are protected and well respected by authorities, user confidence is also gained and the ability to contact tracing tools to provide support for public health authorities achieves the intended goals.

About the author

Oarabile Mudongo is a technologist and a Ford Foundation / Media Democracy Fund Technology Exchange (Tx) fellow. He works with Research ICT Africa as a Research fellow on the Africa AI Policy Project (AIAPP) mapping Artificial Intelligence (AI) usage in Africa and associated governance issues affecting the African continent.