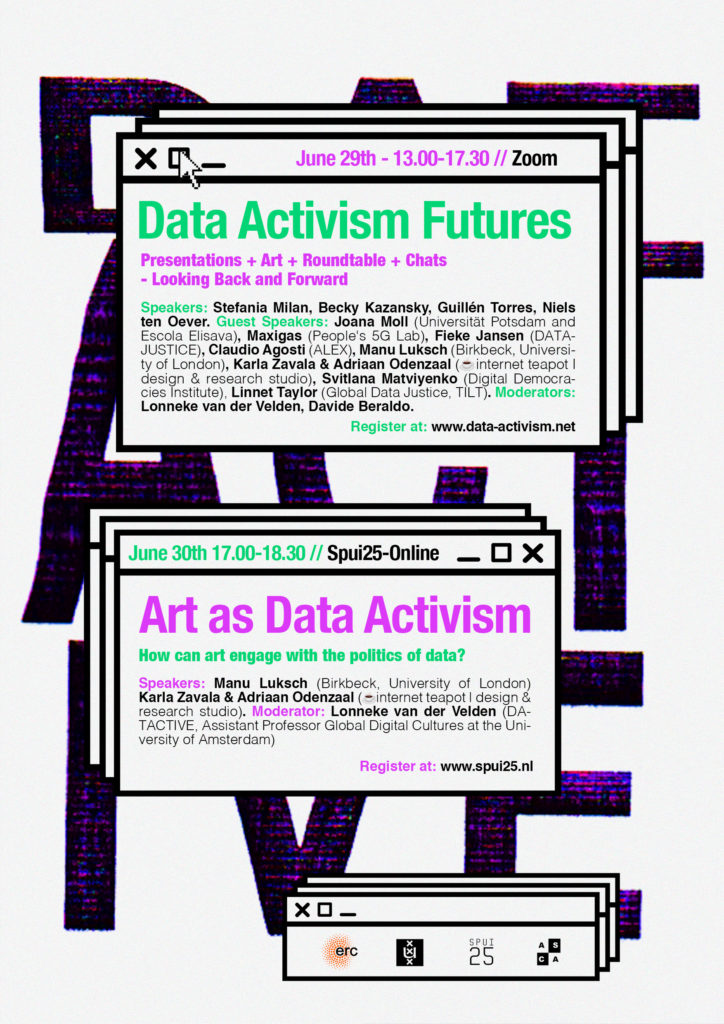

The second day of the DATACTIVE closing workshop, hosted online by SPUI25, focused on artistic responses to datafication and mass data collection. The DATACTIVE team has interviewed many civil society actors from the field of digital rights, privacy, and technology activism. Artists take part in this field, but often they don’t figure as the core actors in what is being highlighted as data activism. In this event, we wanted to stage artistic interventions in particular, in order to tease out what artists do and can do, and what insights and further questions do they generate. In this event we spoke with Karla Zavala and Adriaan Odendaal from The Internet Teapot Design Studio, Manu Luksch, and Viola van Alphen, about their work and ideas:

The Internet Teapot Design Studio is a Rotterdam-based collaboration that focuses on speculative and critical design projects and research. Karla and Adriaan explained how their work is based on the idea that ephemeral data processes have material effects in the world, and that it is needed to focus on the conditions of their production. In order to bring in this focus with their audiences, Karla and Adriaan organize co-creation workshops. In these workshops they aim to create counter-discourses, critical practices, and algorithmic literacy. Part of their approach is working with so called ‘political action cards’, a way to design pathways through the datafied society. In this way, they stimulate creative responses and make people aware of processes of datafication and, for instance, machine learning. One example of such a creative response is participants writing a diary entree from the perspective of a biased machine vision system. By taking the position of the machine, they would imagining processes such as inputs, black boxes, and outputs. Through their workshop, their audience engages with major conceptual themes such as Digital Citizenry, Surveillance Capitalism, Digital Feminism.

Manu Luksch is an intermedia artist and filmmaker who interrogates conceptions of progress and scrutinises the effects of network technologies on social relations, urban space, and political structures. She talked about her work on predictive analysis and how through her work she tries to involve publics in matters of algorithmic decision making. She showed us a part ‘Algo-Rhythm’, a film that “scrutinizes the limitations, errors and abuses of algorithmic representations” . The film, which was shot in Dakar in collaboration with leading Sengalese hip-hop performers, addresses practices of political microtargeting. As she explained, the film is an example of how she frames her findings in a speculative narrative on the basis of observations and analyses. The film got translated in eight languages and has been included in curricula across schools in Germany, which shows how her work finds a place outside of the more classic art settings and operates as a societal intervention.

Viola van Alphen is an activist, writer, and the creative director and curator of Manifestations, an annual Art & Tech festival in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. Viola showed us trailers of Manifestations, and explained how ‘fun’ is an important element for passing the message on an art and technology festival. She provided many examples of how artists try to materialize datafication and concerns around the digital economy. Some of these examples included a baby outfit with an integrated smartphone, data poker games, and candy machines that give candies in return for personal data. She also told us about her experiences of hosting the exhibition online in virtual worlds, and how artists typically managed to push the boundaries of the platform and be kicked off the platform. This, in turn, exhibits ‘the rule of platforms’, but how artists found counter measures via alternative self-hosted and decentralized servers. Other examples included 3D printed face masks that would confuse the Instagram facial recognition system, and a film that disclosed how corporations, including ones that sponsored the exhibition, take part in the weapon industry. For her, artists are important in making complex issues about datafication simple. They can boil them down to a key problem and make that sensible.

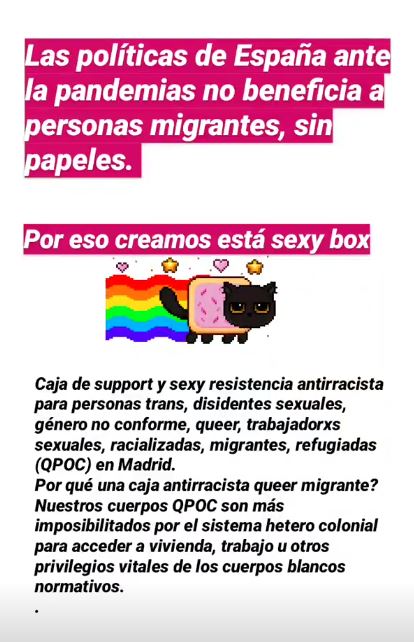

In the discussion, we touched upon a variety of issues. In our DATACTIVE workshop, we have talked about the question whether the context of datafication has changed over the last 5-6 years. This question is important to us, because the project started in the wake of the Snowden disclosures and questions about mass data collection and security were relatively new to the larger audience. The Internet Teapot Design Studio addressed how the practices of data tracing and identification are seemingly much more present in the public domain now. Adriaan mentioned how tactics of ‘gaming the system’ are present on social media, and not only amongst the typical tech activists. According to him, algorithmic awareness has become more part of public discourse, as shown by Instagram influencers talking about gaming the algorithms. Karla added how, during social protests in Colombia, tips were being shared about how beauty filters can be repurposed to prevent online facial recognition software to recognize people. They find it interesting to see user generated content emerging that is critical about algorithms.

In response the question about societal change, Manu pointed to the fact that datafication existed also before the digital, and that for years, fears to be outpaced by technological competition hindered data regulation. She stated that it is an urgent task to remind ourselves that data is not immaterial, and that it is not some substrate that we sweat out. She commented that, when looking back, the notion of the ‘data shadow’, a concept that has been used to explain our ‘data profiles’, was maybe an attractive but an ‘unlucky choice’. Data is rather an extension, that opens and closes doors. In other words, data has much more agency than being just a trace that we leave behind.

We also talked about the question whether the artists follow up with their audiences. All participants work on awareness raising. But are people really empowered on the longer term? According Viola, who regularly ‘tests out’ ideas for her exhibition with neighbors and friends, it is important to break out of one’s bubble. Art can touch individual people in their hart, and they might remember single art projects for years, but one needs to invest in speaking a variety of languages. Amongst her visitors are professionals, kids, refugees, and corporate stakeholders. Sustaining awareness is both a continuous and customized process.

The Teapot Design Studio does see communities emerging that keep in touch via social media after workshops. The studio can function as a stepping stone for people to get familiar with the topic, after which they might hopefully become interested in bigger events such as Ars Electronica or Mozilla Fest.

We concluded the event with the following question: If you were looking forward to the future, what methods are needed? What approaches would you teach art students? The Teapot studio stated that one shouldn’t be intimidated by tech in a material way. And also: Digital media is not new: people need to work on understanding what is the post-digital and what are its aesthetics. Manu advises people to take their time to become data literate, develop their sense for values (including values and skills associated to the analogue space and time), and never stop dreaming. Viola states that art projects need to be easy and digestible with only one headline. If people don’t understand it in one minute, they are off again.

There is much more to know. Watch the video of our event to hear Karla and Adriaan about what ‘teapots’ have to do with the internet, to understand how Manu has investigated the way legal regimes co-shape what is returned as ‘an image’ after doing FOIA requests in the context of CCTV surveillance, and to hear Viola reflect upon how robots can provide multi-sensory experiences and raise questions about war. The DATACTIVE team is looking forward to follow the work of the speakers in the coming years. Some of work discussed in the event is also accessible through our website.

The first day of DATACTIVE’s final event also featured a more condensed, albeit exciting panel dedicated to the intersections between data / art / activism. Next to the artists already mentioned above, we also had the opportunity to have a peek on the work of Joana Moll, a Barcelona/Berlin based artist and researcher whose work critically explores the way techno-capitalist narratives affect the alphabetization of machines, humans and ecosystems. Stay tuned for more info on this event in an upcoming post!