Rolien Hoyng and Sherry Shek discuss the multiple relations between open data and data sovereignty, interrogating their compatibility.

by Rolien Hoyng and Sherry Shek

Open Data and Data Sovereignty both seem desirable principles in data politics. But are they compatible? For different reasons, these principles might be mutually exclusive in so-called open societies with free markets of information as well as in restrictive contexts such as China. Hong Kong, which combines traits of both societies, shows the promises and dangers of both principles and the need for a new vision beyond current laws and protocols.

What are Open Data and Data Sovereignty

Open Data refers to free and unrestrained access to data, to be used by anyone for whatever purpose. Open Data initiatives are usually adopted and led by governments who open up data they collect or generate related to census, economy, government budget and operation, among others.

Open Data initiatives have been touted to democratize information and enhance citizen participation. Individuals, communities, and intermediaries such as journalists, data activists, and civic hackers can produce critical insights on the basis of Open Data, to hold governments accountable, or self-organize to undertake community projects for their own betterment. This approach to Open Data reflects a democratic ideal. Individuals and communities possess political rights, which include control over their own data, as well as access to data about their communities, their government, and society at large. This is also how Data Sovereignty can be realized.

Open Data’s irreverence

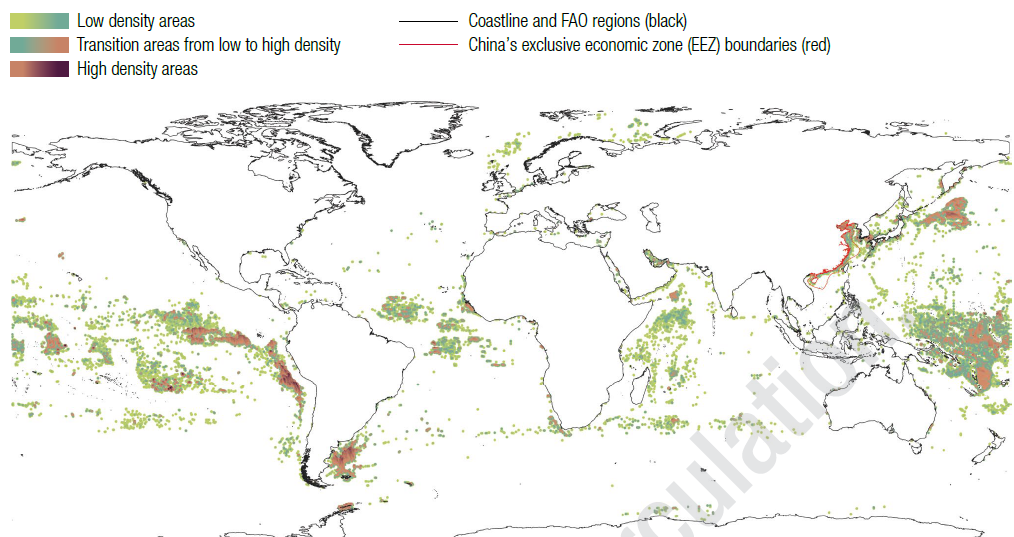

But a more critical look shows that Open Data can also violate Data Sovereignty. The democratic ideal of Open Data does not easily realize itself. In actuality, Open Data initiatives often primarily serve economic strategies to stimulate innovation and data-driven industries, which becomes clear in the kinds of datasets that are released. The practice of Open Data also seems more problematic when placed in the context of indigenous peoples’ struggles. In Australia and elsewhere, colonial struggles have historically involved control over knowledge and information from and about tribes. Such struggles continue today in the age of data-driven innovation, which produces new forms of data extraction and discrimination especially at the social margins of current societies. Given that Open Data may aid or intensify such processes, it is not always, or only, innocent.

To observe the principle of Data Sovereignty, it is important that data is managed in a way that aligns with the laws, ethical sensibilities, and customs of a nation state, group, or tribe. Though the concern around data sharing, sales, and (re)use is commonly framed in terms of privacy, the principle of Data Sovereignty demands a more expansive view. Societies that do not question data usage in light of the rights of the people whom the data is about may be considered free markets for information, but they don’t offer Data Sovereignty.

Data politics in China

For China, Open Data is vital to its pursuit of global leadership in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and developing commercial and government platforms that function as the infrastructures of everyday life. But the country also has recently made global news with path-breaking laws constraining the unlimited use of data and development of AI, which seem in some respects to exceed the EU’s privacy-oriented GDPR and enhance Data Sovereignty. So far, however, Data Sovereignty in China has been interpreted foremost in a statist way: the state rather than the individual or the community controls usage of data.

The tension between Open Data and Data Sovereignty is reconciled in China by formal procedures that create room for withholding data from the public in the name of protecting sensitive information and state secrets. For instance, according to the definition of Open Data by the Open Knowledge Foundation, all datasets should be provided under the same “open” license, allowing individuals to use the datasets with the least restrictions possible. But in the Chinese context, user registration is required for access to certain datasets. Providing differentiated access to data is seen by local experts as a preferable and advanced solution to the security concerns that Open Data brings to bear. For instance, Shanghai’s recently introduced Data Regulation categorizes certain public data to only be “conditionally open”, including those that require high data security and processing capabilities, are time-sensitive, or need continuous access. Worries remain though because seemingly “innocent” data such as average income levels can always be repurposed and rearticulated, and hence become a threat.

Data politics in Hong Kong

During the 2010s, rendering datasets openly available was key to the endeavor to transform Hong Kong into Asia’s “smart” world city, serving the goal of building “a world-famed Smart Hong Kong characterized by a strong economy and high quality of living”, as the Hong Kong government framed it. But the smart-city turn also gave new momentum to old struggles over data and information. Right before the 1997 Handover of Hong Kong from Britain to mainland China, the colonial regime resisted calls for a Freedom of Information Bill, and until today there is no law in Hong Kong to provide the public the legal right to access government-held information. With the government’s turn to Open Data, data advocacy flourished and the struggle for access to information found new means.

The momentum did not last in the face of new political struggles. In her election manifesto in 2017, Carrie Lam stated that she held a positive view of the Archives Law and would follow up upon taking office. She also promised “a new style of governance,” making government information and data more transparent for the sake of social policy research and public participation. In 2018, Lam’s Policy Address announced a review of the Code on Access to Information, which provides a non-legally binding framework for public access to government-held information. However, since the turbulent events of 2019-2020, there has been no mention of Open Data, Archives Law, or the Code on Access to Information in addresses by Lam. The Law Reform Commission Sub-committee still is to come forward with a follow-up on its 2018 consultation paper.

Neither open nor closed

Reconciling an Open Data regime that supports data-driven economic development and a Data Sovereignty regime that is increasingly statist, data in Hong Kong is neither truly “open” nor “restricted.” A systematic and codified approach to Data Sovereignty along the lines of mainland China’s is lacking. But some recent events suggest a more ad hocapproach to incidents in which otherwise mundane data suddenly turn out to be politically sensitive. For instance, the journalist Choy Yuk-ling was arrested in November 2020 and found guilty later of making false statements to obtain vehicle ownership records. She collected the data for an investigative journalism project related to the gang violence that unfolded in the district of Yuen Long on the night of July 21, 2019, and that targeted protesters and members of the public.

The application for access to vehicle records asks requesters to state their purpose of applying for a Certificate of Particulars of Motor Vehicle. It used to be the case that, next to legal proceedings and sale and purchase of vehicles, there was a third option, namely “other, please specify,” though the fine print already restricted usage to traffic and transportation matters. But since October 2019, this third option has changed, now explicitly excluding anything else other than traffic and transport related matters. Such checkbox politics indicate that seemingly mundane data can suddenly become the center of controversy.

Other seemingly minor, bureaucratic changes likewise seek to affix data and constrain their free use: the Company and Land Registry has started to request formal identification of data requesters, something that members of the press have expressed to put journalists at risk.

These changes suggest that while a full-fledged strategy serving statist Data Sovereignty remains absent in Hong Kong and the stated reason for new restrictions is personal privacy instead, the use of data is not entirely free and open either. Interestingly though, recent political and legal developments in Hong Kong have so far not prevented the city’s climb in the ranks of the Open Data Inventory, conducted by Open Data Watch. In the past year, Hong Kong moved from the 14th rank to the 12th, while mainland China fell to the 155th position. Yet some civic Open Data advocates have drawn their own conclusions after the implementation of the National Security Law in 2020. The organizer of a now disbanded civic data group argued that the law draws an invisible redline and practitioners can’t bear the risk that their use of data is found illegal.

Envisioning Open Data Sovereignty

As a place at the crossroads of diverse geopolitical and technological influences, Hong Kong offers a critical lens on the data politics of both so-called open societies and controlling ones. The unrestricted availability of data as customary in open societies that are pushing for smart cities and data-driven industries can undermine Data Sovereignty by ignoring the rights of individuals and communities to whom the data pertain. But restrictions or conditions regarding data usage enacted in the name of Data Sovereignty can hinder freedoms, too. While all too obvious in the case of regimes abiding by statist Data Sovereignty, the tension between the latter principle and Open Data runs deeper. After all, the potential of data to be repurposed, recontextualized, and rearticulated always implies both threat and possibility. Current Open Data rankings and Data Sovereignty laws alike are insufficient to guide us through this conundrum. More critical nuance and imagination is needed to conceive something as elusive as Open Data Sovereignty.

About the authors

Rolien Hoyng is an Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism and Communication at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her work is primarily situated in Hong Kong and Istanbul and addressed digital infrastructures, technological practices, and urban and ecological politics.

Sherry Shek, is a graduate student in the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Her research addresses global internet governance and China. She has previously worked for the Internet Society of Hong Kong and specialized in Open Data.