Author: Miren Gutierrez

In spite of what we know about how big data are employed to spy on us, manipulate us, lie to us and control us, there are still people who get excited by hype-generating narratives around social media influence, machine learning and business insights. At the other end of the spectrum, there is apocalyptic talk that preaches that we must become digital anchorites in small, secluded and secret cyber-cloisters.

Don’t get me wrong; I am a big fan of encryption and virtual private networks. And yes, the CEOs of the technology corporations have more resources than governments to understand social and individual realities. The consequence of this unevenness is evident because companies do not share their information unless forced or in exchange for something else. Thus, public representatives and citizens lose their capacity for action vis-à-vis private powers.

But precisely because of the severe imbalances in practices of dataveillance (van Dijck 2014) it is vital to consider alternative forms of data that enable the less powerful to act with agency (Poell, Kennedy, and van Dijck 2015) in the era of the so-called “data power”. While the debate on big data is hijacked by techno-utopians and techno-pessimists and the big data progress stories come from the private sector, little is being said about what ordinary people and non-governmental organisations do with data; namely, how data are created, amassed and used by alternative actors to come up with their own diagnoses and solutions.

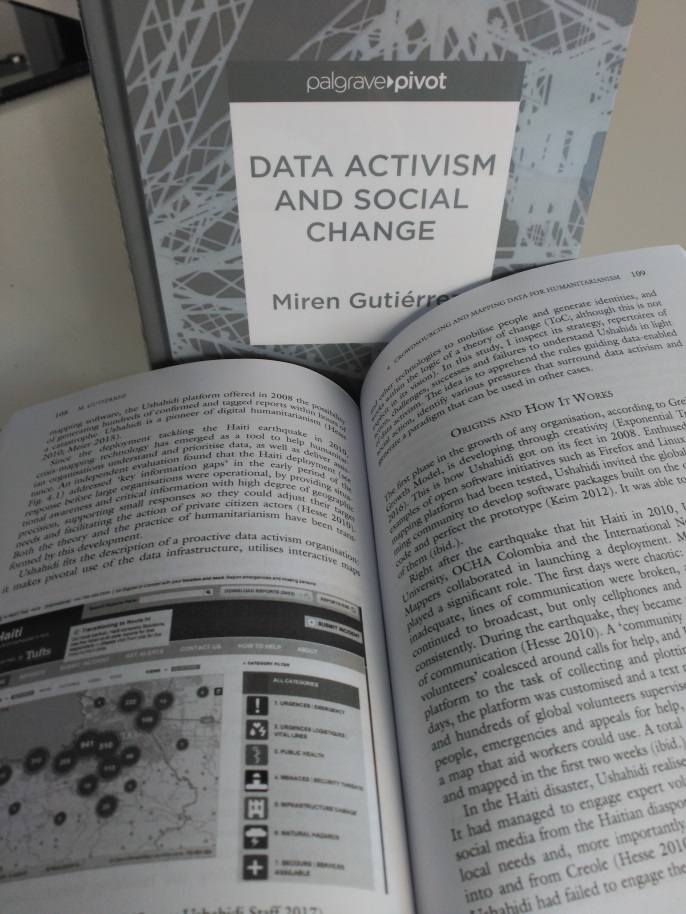

My new book Data activism and social change talks about how people and organised society are using the data infrastructure as a critical instrument in their quests. These people include fellow action-oriented researchers and number-churning practitioners and citizens generating new maps, platforms and alliances for a better world. And they are showing a high degree of ingenuity, against the odds.

The starting point of this book is an article in which Stefania Milan and I set the scene, link data activism to the tradition of citizens’ media and lay out the fundamental questions surrounding this new phenomenon (Milan and Gutierrez 2015).

Most of the thirty activists, practitioners and researchers I interviewed and forty plus organisations I observed for the book practice data activism in one way or another. In my analysis, I classify them in four not-so-neat boxes: These include skills transferrers, or organisations, such as DataKind, that transfer skills by deploying data scientists into non-governmental organisations so they can work together on projects. Other skills transferrers, for example, Medialab-Prado and Civio, create platforms and tools or generate the matchmaking opportunities for actors to meet and collaborate in data projects with social goals.

A second group –including catalysts such as the Open Knowledge Foundation— sponsor some of these endeavours. Journalism producers can include journalistic organisations such as the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, or civil society organisations, such as Civio, providing analysis that can support campaigns and advocacy efforts.

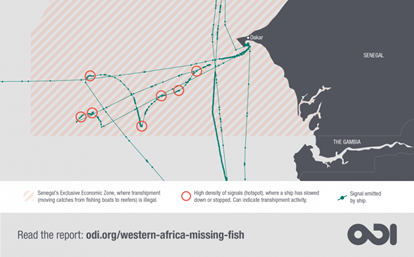

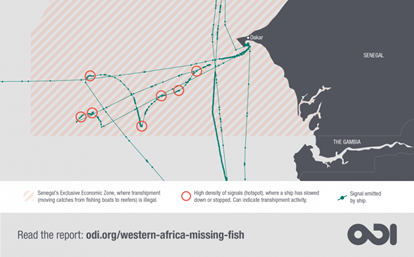

This is a moment in the Western Africa’s Missing Fish map where irregular fish transshipments are being conducted in Senegal waters. See interactive map here.

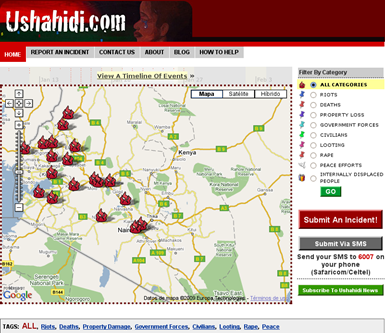

Proper data activists take it further, securing in sheltered archives vital information and evidence of human rights abuses (i.e. The Syrian Archive); recreating stories of human suffering and abuse (i.e. Forensic Architecture’s “Liquid Traces”); tracking illegal fishing and linking it to development issues (i.e. “Western Africa’s Missing Fish”, co-led by me at the Overseas Development Institute); visualising evictions and mobilising crowds to stop them (i.e. in San Francisco and Spain); and mapping citizen data to produce verified and actionable information during humanitarian crises and emergencies (i.e. the “Ayuda Ecuador” application of the Ushahidi platform), to mention just a few.

This classification is offered as a heuristic tool to think more methodically about real cases of data activism, and also to guide efforts to generate more projects.

We know datasets and algorithms do not speak for themselves and are not neutral. Data cannot be raw (Gitelman 2013); data and metadata are “made” in processes that are “made” as well (Boellstorff 2013). That is, data are not to be treated as natural resources, inevitable and spontaneous, but as cultural resources that to be curated and stored. And the fact that the data infrastructure is employed in good causes does not abolish the prejudices and asymmetries present in datasets, algorithms, hardware and data processes. But the exciting thing is that even using flawed technology, these activists gets results.

But where do these activists get data from? Because data can be difficult to find…

How do activists get their hands on data?

Corporations do not usually give their data away, and the level of government openness is not fantastic. “Data is hard (or even impossible) to find online, 2) data is often not readily usable, 3) open licensing is rare practice and jeopardised by a lack of standards” (Global Open Data Index 2017). This lack of open access to public data is shocking when considering this is mostly information about how governments administer everyone’s resources and taxes.

So when governments and corporations do not open their data vaults, people get organised and generate their own data. This is the case of “Rede InfoAmazonia”, a project that maps water quality and quantity based on a network of sensors deployed by communities of the Brazilian Amazon. The map issues alarms to the community when water levels or quality surpass or fall behind a range of standard indicators.

In my book, I discuss five ways in which data activists and practitioners can get their hands on data: from the simplest to the most complex, 1) someone else (i.e. a whistle-blower) can offer them the data; 2) data activists can also resort to public data that can be acquired (i.e. automatic identification system signals captured by satellites from vessels) or are simply open; 3) they can generate communities to crowdsource citizen data; 4) they can appropriate data or resort to data scraping; and 5) they deploy drones and sensors to gather images or obtain data via primary research (i.e. surveys). Again, this taxonomy is offered as a tool to examine real cases.

Of them, crowdsourcing data can be a powerful process. The crowdsourced map set up using the Ushahidi platform in Haiti in 2010 tackled “key information gaps” in the early period of the response before large organisations were operative, providing geolocalised data to small non-governmental organisations that did not have a field presence, offering situational awareness and rapid information with high degree of accuracy, and enabling citizens’ decision-making, found an independent evaluation of the deployment (Morrow, Mock, and Papendieck 2011). The Haiti map marked a transformation in the way emergencies and crises are tackled, giving rise to digital humanitarianism.

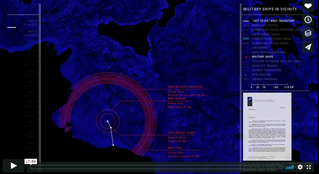

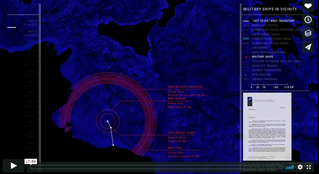

Forensic Architecture’s Liquid Traces.

Other forms of obtaining data are quite impressive too. Forensic Architecture’s “Liquid Traces” employed AIS signals, heat signatures of the ships, radar signals and other surveillance technologies to demonstrate that the failure to save a group of 72 people who had been forced by armed Libyan soldiers on-board of an inflatable craft on March 27, 2011, was due to callousness, not the inability to locate them. Only nine would survive. Another organisation, WeRobotics, helps communities in Nepal to analyse and map vulnerability to landslides in a changing climate.

Alliances, maps and hybridisation

From the observation of how these organisations work, I have identified eleven traits that define data activists and organisations.

One interesting commonality is that data activists tend to work in alliances. This sounds quite commonsensical. Either the problems these activists are trying to analyse and solve are too big to tackle on their own (i.e. from a humanitarian crisis to climate change), or the datasets that they confront are too big (i.e. “Western Africa’s Missing Fish” and the ICIJ’s “Panama papers” processed terabytes of data). I cannot think of any data project that does not include some form of collaboration.

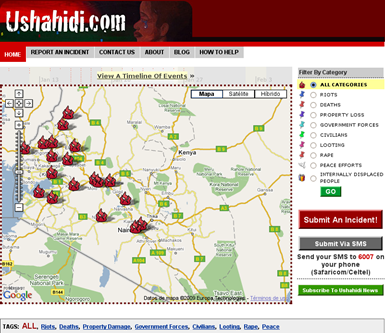

The first Ushahidi map: Kenyan violence.

Another quality is that data activists often rely on maps as tools for analysis, coordination and mobilisation. Maps are objects bestowed with knowledge, power and influence (Denil 2011; Harley 1989; Hohenthal, Minoia, and Pellikka 2017). The rise of digital cartography, mobile media, data crowdsourcing platforms and geographic information systems reinforces the maps’ muscle. This trend overlaps with a growing interest in crisis and activist mapping, a practice that blends the capabilities of the geoweb with humanitarian assistance and campaigning. In the hands of people and organisations, maps have been a form of political counter-power (Gutierrez 2018). One example is Ushahidi’s first map (see map), which was set up in 2008 to bypass an information shutdown during the bloodbath that arose after the presidential elections in Kenya a year earlier, and to give voice to the anonymous victims. The deployment allowed victims to disseminate alternative narratives about the post-electoral violence.

The employment of maps is so usual in data activism that I have called this variety of data activism geoactivism –defined precisely by the way activists use digital cartography and often crowdsourced data to provide alternative narratives and spaces for communication and action. InfoAmazonia, an organisation dedicated to environmental issues and human rights in the Amazon region, is an example of another organisation specialised in visualising geolocalised data, in this case for journalism and advocacy. I defend the idea that this use of maps almost by default has generated a change in paradigm, standardising maps for humanitarianism and activism.

Vagabundos de la chatarra, the book.

Besides, data activists usually do not have any qualms about mixing methods and tools from other trades. Not only many data organisations are hybrid –crossing the lines that separate journalism, advocacy, research and humanitarianism—, but they also combine repertoires of action from different areas. An example is “Los vagabundos de la chatarra”, a year-long project that includes comics journalism, a book, interactive maps, videos and a website to tell the stories of the people who gathered and sold scrap metal for a living on the edges of Barcelona during the economic crisis that started in 2007 (Gutierrez, Rodriguez, and Díaz de Guereñu 2018).

Civio, mentioned before, produces journalism, hosts data projects, advocates around issues such as transparency, corruption, health and forest fires. “España en llamas” is a project hatched at Civio that, for the first time in Spain, paints a comprehensive picture of fires. Civio also opens the data behind these projects.

The values that motivate these data activists include sharing knowledge, collaborating and inspiring processes of social change and justice, uncovering and providing undisputable evidence for them, and deploying collective action powered by indignation and also by hope. These data activists deserve more attention.

*A version of this blog has been published at Medium.

References

Boellstorff, Tom. 2013. ‘Making Big Data, in Theory’. First Monday 18 (10). http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4869/3750.

Denil, Mark. 2011. ‘The Search for a Radical Cartography’. Cartographic Perspectives 68. http://cartographicperspectives.org/index.php/journal/article/view/cp68-denil/14.

Gitelman, Lisa, ed. 2013. Raw Data Is an Oxymoron. Cambridge and London: The MIT Press.

Global Open Data Index. 2017. ‘The GODI 2016/17 Report: The State Of Open Government Data In 2017’. https://index.okfn.org/insights/.

Gutiérrez, Miren. 2018. ‘Maputopias: Cartographies of Knowledge, Communication and Action in the Big Data Society – The Cases of Ushahidi and InfoAmazonia’. GeoJournal 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-018-9853-8.

Gutiérrez, Miren, Pilar Rodríguez, and Juan Manuel Díaz de Guereñu. 2018. ‘Journalism in the Age of Hybridization: Barcelona. Los Vagabundos de La Chatarra – Comics Journalism, Data, Maps and Advocacy’. Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies 10 (1): 43-62. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjcs.10.1.43_1

Harley, John Brian. 1989. ‘Deconstructing the Map’. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization 26 (2): 1–20.

Hohenthal, Johanna, Paola Minoia, and Petri Pellikka. 2017. ‘Mapping Meaning: Critical Cartographies for Participatory Water Management in Taita Hills, Kenya’. The Professional Geographer 69 (3): 383–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2016.1237294.

Milan, Stefania, and Miren Gutiérrez. 2015. ‘Citizens´ Media Meets Big Data: The Emergence of Data Activism’. Mediaciones 14. http://biblioteca.uniminuto.edu/ojs/index.php/med/article/view/1086/1027.

Morrow, Nathan, Nancy Mock, and Adam Papendieck. 2011. ‘Independent Evaluation of the Ushahidi Haiti Project’. Port-au-Prince: ALNAP. http://www.alnap.org/resource/6000.

Poell, Thomas, Helen Kennedy, and Jose van Dijck. 2015. ‘Special Theme: Data & Agency’. Big Data & Society. http://bigdatasoc.blogspot.com.es/2015/12/special-theme-data-agency.html.

van Dijck, Jose. 2014. ‘Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology’. Surveillance & Society 12 (2): 197–208.

About Miren

Miren is a Research Associate at DATACTIVE. She is also a professor of Communication, director of the postgraduate programme “Data analysis, research and communication”, and member of the research team of the Communication Department at the University of Deusto, Spain. Miren’s main interest is proactive data activism, or how the data infrastructure can be utilized for social change in areas such as development, climate change and the environment. She is a Research Associate at the Overseas Development Institute of London, where she leads and participates in data-based projects exploring the intersection between biodiversity loss, environmental crime and development.