By Duncan Kinuthia, Ford/Media Democracy Fund Tech Exchange Fellow at Research ICT Africa

>>> if your Swahili is not good enough, check out the English translation! <<<

Watumizi wa mtandao Afrika wanazidi kuongezeka katika kusaka ughaibu kwenye mtandao. Hii imehamasishwa na ripoti za hivi majuzi za ukiukaji wa uaminifu na faragha wa data katika mitandao ya kijamii. Hii pamoja na kuvuka mpaka katika usalama na udhibiti wa serikali imesababisha kuongezeka kwa vifaa vya ughaibu wa data. Ama kweli, watumizi wanafanya hima ili kuweza kupata habari safi, usalama na faragha mtandaoni. Kwa vile muundo wa mtandao hauruhusu ughaibu kamili, waeza kupata ughaibu huu kwa kutoa majina ama habari itakayokubainisha na kwa kutumia teknolojia fiche katika habari za watumizi wa wavuti. Utumizi wa VPN (Virtual Private Network) imeongezeka kwa watumizi wa wavuti duniani pamoja na makampuni kwa ajili ya ongezeko la teknolojia fiche zipatikanazo kwenye VPN katika usambazaji wa data kwenye mtandao ulio na upungufu wa usalama. Hii imesababisha ukuaji wa maonyesho wa soko la VPN muongo uliopita na pia MarketWatch kuripoti asilimia kumi na nane katika kiwango cha ukuaji kila mwaka. Miunganisho ya VPN imeimarishwa kwa kutumia njia ya teknolojia fiche ikifuatiliwa na uthibitisho ya lazima kwa mtumiaji ili aweze kupata kuunganishwa kwa hiyo VPN.

Afrika imekabiliwa na mlipuko wa matumizi wa simu zilizo na upatikanaji wa mkondoni muongo uliopita ambao umesababisha kuongezeka kwa watumiaji wa mtandao barani Afrika. Mlipuko huu umeleta mageuzi bora ya kiuchumi, kisiasa na kijamii. Mojawapo ikiwa watumiaji zaidi wakiingia katika mitandao ya kijamii ili kuweza kuendelea kuwasiliana na familia na marafiki na hata kueneza shughuli za kiuchumi. Biashara ya wavuti pia imeenea Afrika ikichochewa na ukuaji wa matumizi ya huduma za fedha za simu kote barani. Ilhali utumizi wa mtandao umeleta faida kikandani kuna udhibiti, kuzimisha na kodi ya mitandao ya kijamii pia imezidi. Matendo haya ya kiukaji yaweza kupunguza faida za digitization.

Kwa watumizi wa mtandao wengi Afrika mitandao ya kijamii ndiyo mtandao halisi kwao na gharama kubwa ya bandwidth ndiyo kikwazo kikuu cha utumizi wake. Mfano ni watumizi wa Uganda ambao walihangaishwa na ushuru liyofanywa rasmi kuanzia tarehe moja Julai mwaka wa 2018. Sheria, iliyopitishwa na bunge la Uganda inatia kodi ya shilingi mia mbili za Uganda ($ 0.05) kwa matumizi ya mitandao ya kijamii kila siku. Hii ni sawa na dola 19 ($19) kwa kila mwaka na pamoja na gharama kubwa za bandwidth inazuia sana matumuzi ya mitandao ya kijamii, kutokana na kwamba jumla ya bidhaa za nyumbani kwa kila mtu ilikuwa dola mia sita na nne ($ 604) tu mwaka 2017. Ili kuepuka ushuru wa matumizi ya mitandao ya kijamii, watu wanatafuta njia za kuihepa. Utafiti uliofanywa juu ya kodi ya mitandao ya kijamii nchini Uganda umebaini kwamba asilimia hamsini na saba ya watumiaji waligeuka kwa huduma za VPN ili kuepuka kodi iliyolazimishiwa kwao.

Hata hivyo, hizi sio sababu za pekee ambazo watumiaji wa Afrika wanatumia VPN. Kwa mfano, Kenya, watumiaji wengi wa mtandao hutumia VPN na kuhadaa DNS kuepukana na vitengo vya Geo, ambapo maudhui mengi ya elimu na burudani haipatikani nchini kwa sababu ya leseni, hati miliki na ukosefu wa soko kubwa ili kuhakikisha kurudi kwa uwekezaji, kwa kuwa mtandao bado haujapenya vizuri barani. Huduma hizo zinajumuisha Spotify, vipindi na sinema nyingi kwenye Netflix, muziki wa YouTube, Google Music, Google Play Books, Pandora na huduma zinginezo. Watumiaji wa mtandao wameamua kutumia VPN na kuhadaa DNS ili waweze kupata huduma hizi.

Katika nchi nyingine, matumizi ya mtandao ya kijamii yanaonekana kuwa tishio kwa uanzishwaji, na serikali zimeweka masharti ya kisiasa ya mtandao. Vikwazo vya mtandao vinatumiwa kukabiliana na matumizi ya huduma za VPN ili kupata maudhui yaliyolengwa, kama vile matumizi ya uhusiano wa VPN juu ya mtandao inategemea uhusiano wa mtandao. Idadi kubwa ya vikwazo vya mtandao vilivyoripotiwa katika nchi za Afrika hufanyika wakati wa uchaguzi, juu ya madai ya kudhibiti uenezi wa habari bandia. Wananchi wa Jamhuri ya Kidemokrasia ya Kongo ni waathirika wa hivi karibuni kwa hili, baada ya kuzimwa kamili kwa mtandao wakati wa uchaguzi wa Desemba 30. Nchi nyingine za Kiafrika ambazo zimekuwa na vikwazo vya mtandao ni kama Ethiopia, Cameroon, Gambia na Gabon.

Ufahamu wa kikanda juu ya hatari za ufunuzi wa habari na ukiukaji kwenye wavuti ni duni, kwani wafrika wengi hawajajaliwa kutumia mtandao. Kwa kuongeza, wale wanaotumia mtandao hawajui vitisho vya wavuti. Ripoti ya Utoaji wa Usalama wa Afrika ya 2016 ilibainisha kuwa asilimia hamsini ya waliohojiwa hawakupewa mafunzo ya usalama wa cyber. Hii imechangia kuongezeka kwa gharama za makadirio ya uhalifu wa wavuti, Nigeria ikiwa na gharama kubwa zaidi ya $550 milioni. Hata hivyo, kama matumizi ya mtandao yanakua Afrika, haja ya kuhakikisha usalama wa habari kulinda utambulisho wa watu na matumizi ya bure ya mtandao, huja kama jambo muhimu. Kuelewa mbinu za sasa za ughaibu wa data, zana na mazoea kote kandani na jinsi hatua za usalama za habari zinazotumiwa na watumiaji wa Afrika ni muhimu kwa kuinua ufahamu, na hivyo kuleta ushahidi kwenye mjadala wa sasa wa sera juu ya faragha na usalama mtandaoni kutoka kwa mtazamo wa Afrika.

Mwaka mmoja ujao, nitafanya kazi chini ya Media Democracy Fund Tech Exchange Program, na Research ICT Africa, katika utafiti juu ya udhibiti wa habari katika Afrika Mashariki, ikiwa ni pamoja na matumizi ya mbinu za ughaibu wa data na ufanisi wa DNS, lengo muhimu likiwa kuhusu matumizi ya VPN. Research ICT Afrika ni kundi la wataalam wanaojadili sera ya kikanda ya ICT na wanafanya utafiti mbalimbali juu ya utawala digital, sera na kanuni zinazowezesha sera zilizoarifiwa kwa ajili ya upatikanaji bora, matumizi ya teknolojia ya digital kwa maendeleo ya kiuchumi na kijamii Afrika kwa kutumia ushahidi hakika.

Lengo kuu la mradi wangu wa utafiti ni kuangazia mazoezi ya kutumia VPN kama chombo cha ughaibu wa data katika Afrika Mashariki, kwa watumiaji binafsi na mashirika yasiyo ya faida (NPO).

Miongozo itakayoongoza uchunguzi na utafiti wangu ni haya:

- Ni sababu gani kuu za kutumia VPN kama mbinu ya ughaibu wa data katika Afrika Mashariki?

- Ni nani watumiaji wakuu wa VPN katika Afrika Mashariki na ni nini mwenendo katika vikundi tofauti vya watumiaji kwa umri na jinsia?

- Kwa nini watumiaji wa mtandao na NPO hutumia VPN katika Afrika Mashariki?

- VPN imetumiwa wapi zaidi?

- Na VPN ilitumiwa lini katika Afrika Mashariki?

- VPN na zana zingine za ughaibu wa data zimetumiwaje ili kuhakikisha usalama na ufaragha wa habari Afrika Mashariki?

Utafiti juu ya matumizi ya zana za ughaibu wa data katika Afrika ya Mashariki utakuwa muhimu kwa kueneza ufahamu kwa wanaharakati wa data. Mkusanyiko wa data juu ya mbinu mbali mbali zinazotumiwa na watumiaji wa mtandao katika Afrika ya Mashariki kufikia kutokujulikana kwa mtandao zitatiweka dhahiri mbinu za ubunifu ambazo watu hutumia kuhepa vikwazo vilivyowekwa na mashirika makubwa na serikali.

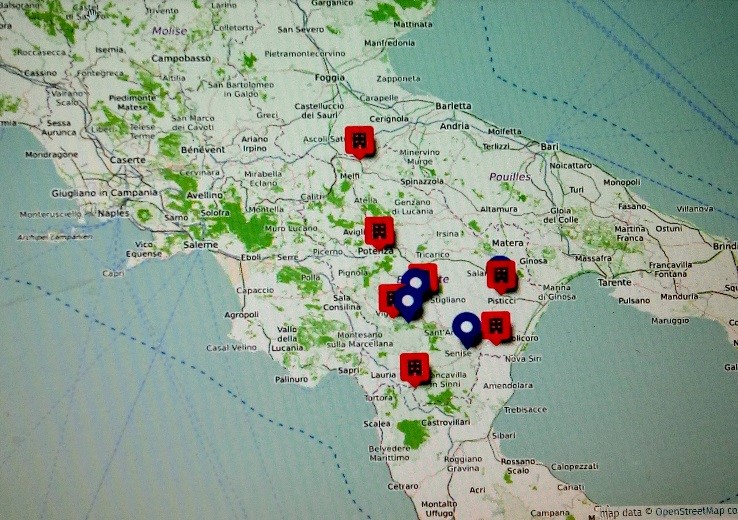

Baadhi ya matokeo ya uchunguzi yataonyesha mienendo ya matumizi ya zana za uonyesho wa data wakati wa vipindi vya uchaguzi wa nchi zilizoathiriwa na kuzimwa kwa mitandao ya kijamii. Utafiti huo utafafanua pia jinsi makundi mbalimbali ya watumiaji hutumia VPN ili kuwezesha upatikanaji wa burudani ya jiji iliyozuiwa pamoja na maudhui ya elimu au usalama wa data kutokana na vipengele vya teknolojia fiche.

Kwa suala la mapendekezo ya sera, utafiti huu utasaidia kuelewa wa dhana ya data kutoka kwa mtazamo wa Kiafrika na utajulisha mjadala wa sera za kikanda na kimataifa juu ya faragha, usalama na usalama mtandaoni katika Afrika. Utafiti huo pia utatoa mapendekezo kwa watumiaji wa internet wa Afrika juu ya jinsi ya kuwa salama mtandaoni kwa njia ya uhamisho wa data kote kanda.