COVID-19 from the Margins was launched at the beginning of May 2020 as a multilingual blog platform, with the aim to give voice to narratives on the pandemic from social groups and individuals invisibilized by mainstream coverage and policies.. Two months down the line, we reflect on the core threads emerged so far, with a look to the future of South-based narrations of the first pandemic of the datafied society.

by Silvia Masiero, Stefania Milan and Emiliano Treré

Since the World Health Organisation declared the outbreak of COVID-19 a pandemic on 11 March 2020, narratives of the virus outbreak centred on counting and measuring have became dominant in public discourse. Enumerating and comparing cases and locations, victims or the progressive occupancy of intensive care units, policymakers and experts alike have turned data into the condition of existence of the first pandemic of the datafied society. However, many communities at the margins—from workers in the informal economy to low-income countries to victims of domestic violence—were left in the dark.

This is why our attention of researchers of datafication across the many Souths inhabiting the globe turned into the untold stories of the pandemic. We decided to make space for narratives from those individuals, communities, countries and regions that have thus far remained at the margins of global news reports and relief efforts. The multilingual blog COVID-19 from the Margins, launched on 4 May 2020, hosts stories of invisibility, including from migrants and communities living in countries and regions with limited statistical capacity or in cities and slums where pre-existing inequality and vulnerability have been augmented by the pandemic. In entering the third month of this initiative, a reflection on the main threads emerged from the 28 articles published so far is in order to devise our look to the future. In what follows, we identify four threads that have informed discussions on this blog so far, namely data visualisation, perpetuated vulnerabilities and inequalities, datafied social policies, and digital activism at the time of the pandemic.

Human invisibilities: Counting at the time of the pandemic

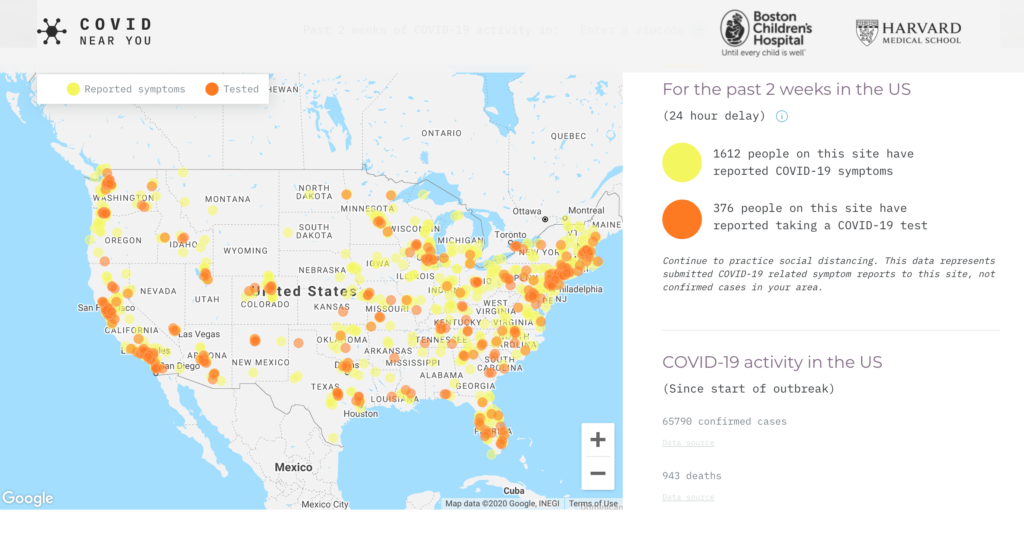

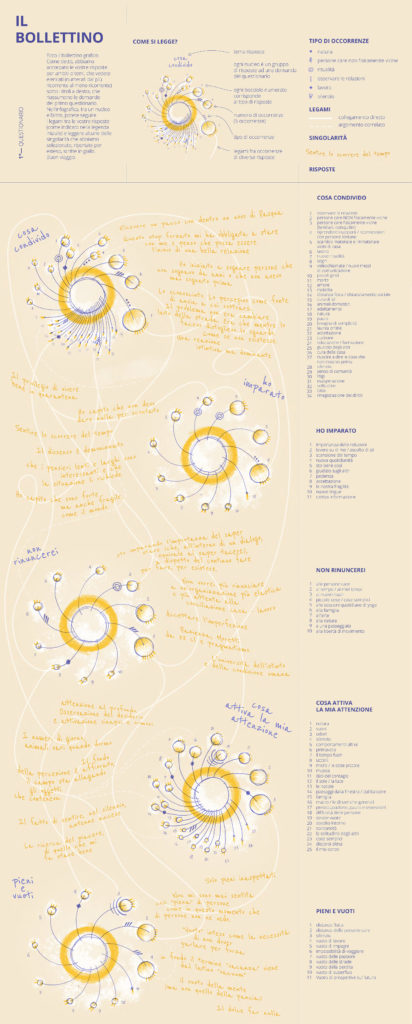

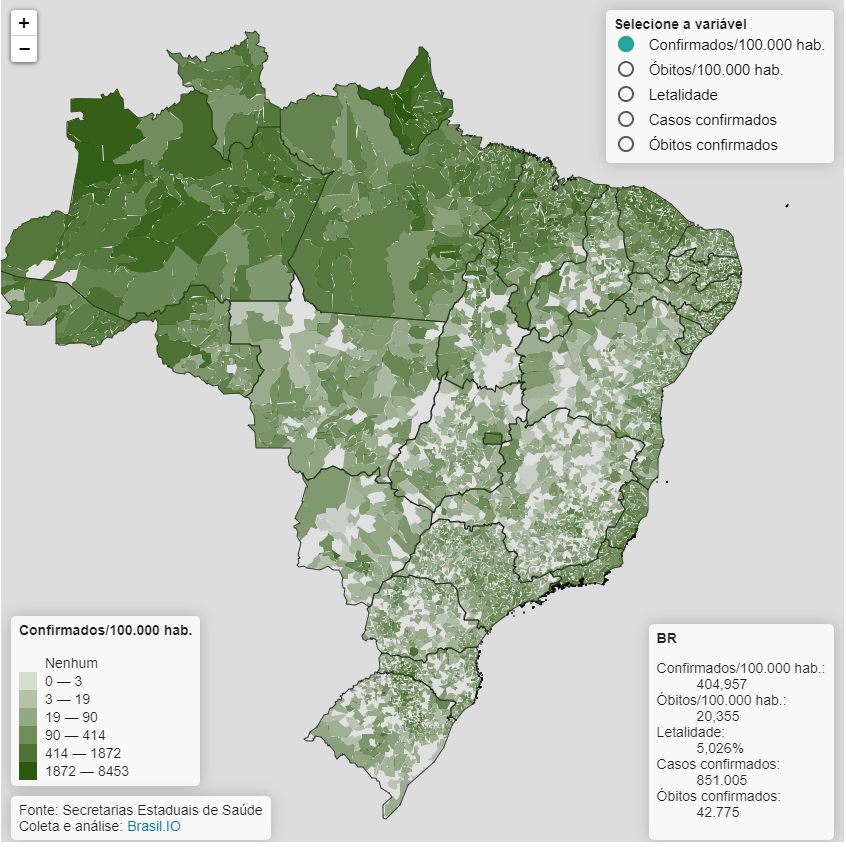

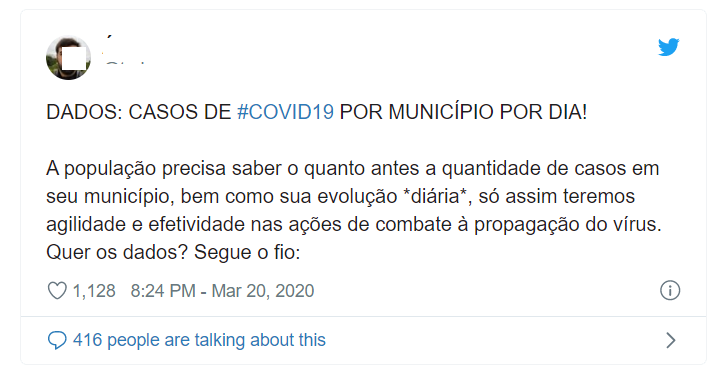

The inaugural piece of COVID-19 from the Margins pointed to the widening data divide that communities in the Souths are subjected to. In a strong exemplification of this problem, the blog hosted a contribution exploring conditions of (in)visibility affecting migrant communities during the pandemic, raising concerns about a just data management applied to populations on the move. As it became publicly noticeable in this global health crisis, data visualisation has important implications for data interpretation and management: a recent post from Italy narrates how local communities make sense of data, building collective learning experiences in the process. Consequently, the blog has turned to those communities whose vulnerability results in particular needs for visibility and visualisation.

Feminist data visualisations, giving visibility to statistics on impacts of COVID-19 on domestic violence and female education rates, offer a means to deal with one such vulnerability. Children from families affected from poverty and precariousness, as well as communities working in the informal sector of countries affected by the pandemic, need to make themselves visible to the state to become the recipients of social policy measures such as subsidies that are vital in situations of crisis. Through multiple narratives from the world, posts published on this blog have revealed the key role of (good) data visualisation in times of crises, and its consequences on governments’ ability to cater effectively to vulnerable groups.

Perpetuated vulnerabilities and inequalities

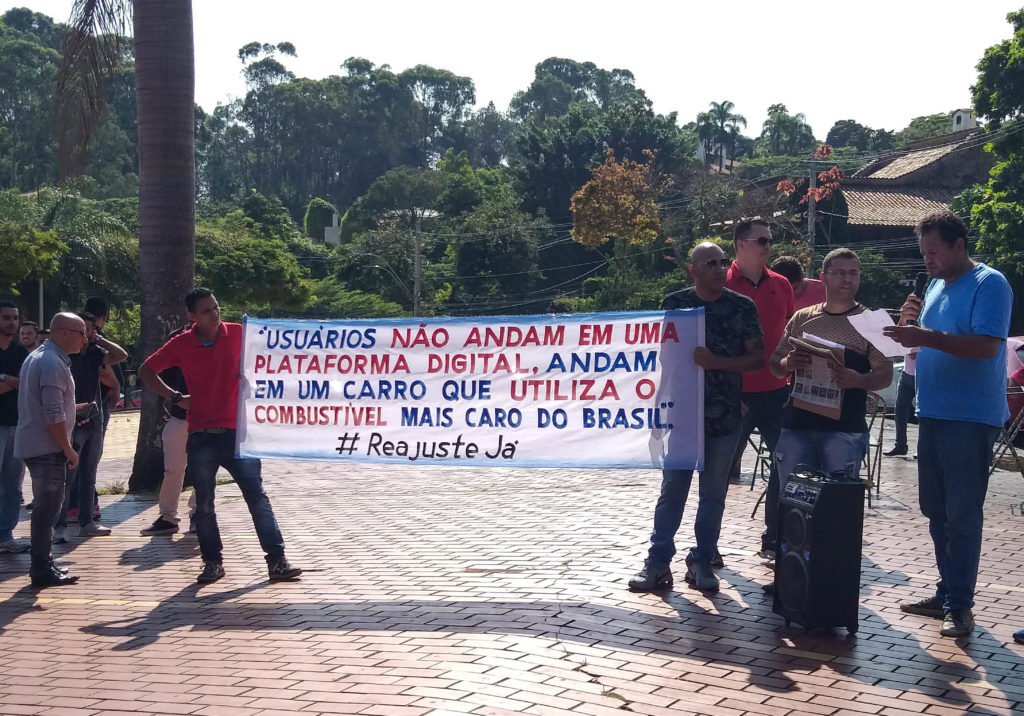

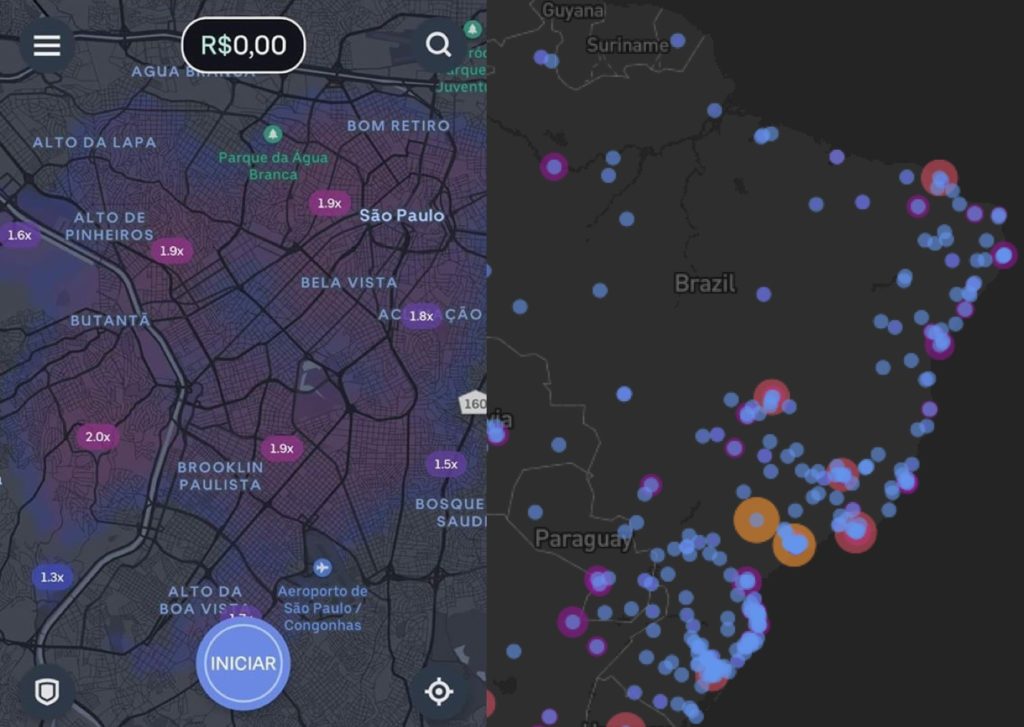

Authors writing for the blog have illuminated the situations of perpetuated vulnerability affecting a variety of communities during the COVID-19 emergency. In a post on the struggles experienced by the LGBTQ+ community it has been noted that, as “stay at home” becomes the new normal, ingrained societal prejudice may result in leaving LGBTQ+ community members without a home to stay in. An article on the struggles of digital economy workers, specifically ride-hailing workers in Brazil, has observed the perpetuation of uncertainty under COVID-19, leaving workers unable to hold public and private entities accountable for the health and economic risks suffered under the pandemic. A post on the emergency in São Paulo, Brazil, has illustrated the perpetuation of socio-economic inequalities under the pandemic, with historically poor and disadvantaged areas of the city suffering the most serious consequences of the health crisis.

Along these lines, one of our opening posts had already noted that, in times of global crisis and vulnerability, ordinary measures of social assistance acquire special importance for those affected. In this light, the narratives of perpetuated vulnerability and inequality unfolding under the pandemic become crucial, as they highlight critical situations that—crystallised under the context of the global crisis— require ad-hoc forms of intervention to limit the profound socioeconomic impacts of the health emergency.

Datafied social policies: A new importance under COVID-19

As national lockdowns, translating into different measures across the world, took hold of civil societies during COVID-19, vulnerable groups including below-poverty-line households, refugees, internally displaced persons, and workers from the informal sector whose income depends on the outputs of daily work, have been disproportionately affected by the crisis. Stories from Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, India, Peru and Spain have highlighted the importance of social policies in emergency, as well as the consequences of datafication on such policies in the current time. While portraying different country cases, these narratives find at least two common denominators. Firstly, they point to the importance of information in devising social protection policy, and primarily, information on who is entitled to emergency assistance and on the size of such entitlements. Datafication reifies existing determination of entitlements and, in the cases of narrow targeting narrated on this blog, it exposes the consequences of making social assistance conditional to strict entitlement criteria.

A second theme exposed by the blog points to the problematic consequences of making social welfare conditional to digital identification, in a time at which vulnerability is heightened by the crisis. In India, where security concerns have emerged around the national contact-tracing app, a pre-existing ecosystem of digital identification centred on Aadhaar (the largest biometric database worldwide) has revealed the perils of perpetuating biometric access to social protection during lockdown. Such perils pertain to the use of biometrics as a means to combat inclusion errors rather than wrongful exclusions, contributing to ban access for the non-entitled but not to ensure access or data justice to the wrongfully excluded. The reshuffled priorities of the global emergency posed by COVID-19 powerfully illustrate such issues, effectively questioning the ethics of targeting and its impact on social assistance programs.

Digital and Data Activism during COVID-19

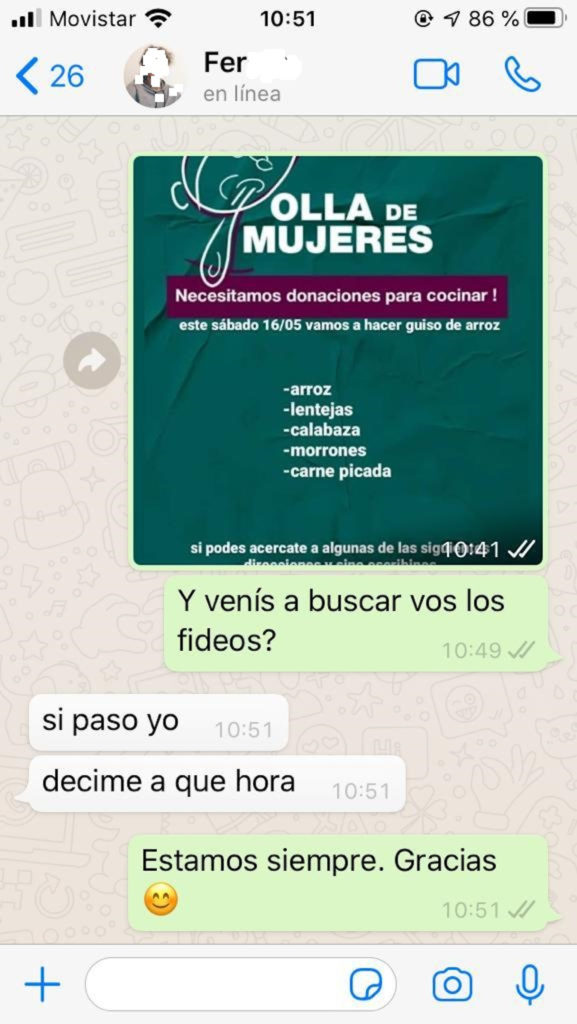

Narratives of digital power from multiple contexts, including China and Russia, have been explored in relation to COVID-19. These narratives have been key in formulating questions around digital activism during the pandemic, interrogating the affordances of extant platforms on providing information and support to vulnerable groups during the crisis. A post from Argentina explored the usage of the instant messaging service WhatsApp in coordinating solidarity groups catering to vulnerable people, while a post centred on Latin America provided context on the anatomy of biopolitics experienced during COVID-19. In continuity with such discourses, one of the most recent posts published on the blog discusses citizen sensing as an affordance of activism in the datafied society, exploring the implications of such a practice under COVID-19.

In appraising the perpetuation of socio-economic vulnerabilities under the pandemic, understanding the affordances of digital platforms in catering and giving voice to the excluded is crucial. It is also of primary importance to understand the risks posed by datafication in the current scenario, and to balance considerations of privacy and security with such affordances. In the present situation, the devising of novel means of digital activism respectful of social distancing measures—such as the digital march of Desaparecidos’ mothers in Mexico—exposes the new facets that activism may acquire under the predicaments of COVID-19.

Looking forward

As the blog enters its third month of activity, reflecting on the medium and long-term consequences of the pandemic—with lockdowns progressively being eased in many corners of the globe and yet more vulnerabilities unfolding for the communities narrated here—will be crucial. In this rapidly evolving scenario, we remain committed to giving voice to global, multilingual narratives about the effects of the pandemic on the Souths, in the hope of consolidating the blog as a space for the multiple, different untold stories of COVID-19 from the Margins to be narrated, amplified and circulated.