Por Stefania Milan y Emiliano Treré

Traducido del inglés por Miren Gutiérrez y revisado por Emiliano Treré y Alejandro Barranquero. ¡Mil gracias a Miren y Alejandro por su preciosa ayuda!

El 15 de julio de 2017, en Cartagena, Colombia, unos cincuenta académicos, académicas y activistas se reunieron para imaginar cómo serían los “Big Data desde el Sur”. Organizado con pocos recursos aunque con mucho entusiasmo por los dos* -justo antes de la Conferencia anual de la IAMCR en Cartagena-, el evento fue diseñado con el objeto de plantear un cambio “de los medios a las mediaciones, de la dataficación al activismo de datos”, como sugiere el título de la conferencia. Pensamos que esta hermosa joya del Caribe, en los márgenes geográficos de un país que acaba de comenzar a inventar un futuro pacífico, sería el lugar más apropiado para iniciar una conversación muy necesaria sobre una serie de preguntas que nos han mantenido a ambos ocupados en los últimos años: ¿Cómo se vería la dataficación “al revés”? ¿Qué preguntas haríamos? ¿Qué conceptos, teorías y métodos adoptaríamos o tendríamos que idear? ¿Qué nos perdemos si acogemos las perspectivas convencionales occidentales? En esta publicación, reanudamos la conversación que iniciamos en Cartagena, mirando hacia adelante.

La dataficación y sus descontentos: ¿Más allá de Occidente?

La dataficación ha alterado dramáticamente la forma en que entendemos el mundo que nos rodea. Comprender los llamados “big data” significa explorar las profundas consecuencias del giro computacional, sus consecuencias en la epistemología, la ontología y la ética, así como las limitaciones, errores y sesgos que afectan la recopilación, la interpretación y el acceso a los datos. Aunque estudiosos y estudiosas de varias disciplinas han comenzado a explorar críticamente las implicaciones de la dataficación en lo que respecta a distintos aspectos sociales, culturales y políticos, gran parte de la crítica académica ha surgido desde una perspectiva occidental que conecta con Silicon Valley, Cambridge, MA y el norte de Europa. Creemos que algo falta en esta conversación.

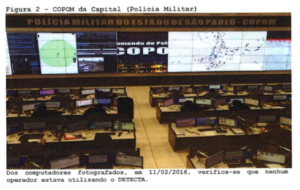

Sin embargo, ya sabemos mucho. El campo emergente de los estudios críticos de datos, en la intersección de las ciencias sociales y las humanidades, nos interpela sobre la desigualdad, la discriminación y la exclusión que alberga la infraestructura “big data” (Gangadharan 2012; Dalton, Taylor y Thatcher 2016). Nos recuerda que los “big data” no son meramente un tema tecnológico o un instrumento del conocimiento, innovación o cambio, sino una “mitología” que debe ser interrogada y abordada críticamente (i.e. boyd & Crawford 2012; Mosco 2014; Tufekci 2014; Van Dijck, 2014). Nos recuerda que, a pesar de ser retratados con las narrativas del positivismo y la modernización, y ser ampliamente elogiados por sus posibilidades revolucionarias en términos de, por ejemplo, participación ciudadana, los “big data” no están exentos de riesgos y amenazas, al tiempo que regímenes opacos de control y manipulación adoptan un papel central en su gestión (ver Andrejevic 2012; Turow 2012; Beer & Burrows 2013; Gillespie 2014; Elmer, Langlois y Redden 2015). La expansión de las prácticas de minería de datos tanto por parte de las empresas como de los estados genera preguntas críticas sobre la vigilancia sistemática y la invasión de la privacidad (Lyon, 2014; Zuboff 2016; Dencik, Hintz y Cable 2016). Preguntas críticas surgen también de las formas en que la academia y las empresas se relacionan con los “big data” y la dataficación: la “grandeza” de los enfoques contemporáneos sobre los datos ha sido cuestionada (Kitchin y Laurialt 2014), y ello nos ha alentado a prestar atención a las prácticas ciudadanas (Couldry & Powell 2014) y a las formas de compromiso crítico diario con los datos (Kennedy y Hill 2017).

¿Pero cómo se desarrolla la dataficación en países con democracias frágiles, economías endebles y pobreza? ¿Es nuestra caja de herramientas teórica y metodológica capaz de captar y comprender tanto los sombríos desarrollos como la sorprendente creatividad que emergen en la periferia del imperio? Hacemos un llamamiento a los descontentos y descontentas de la dataficación para que unan sus fuerzas y aborden conjuntamente estas preocupaciones a fin de abordar preguntas más críticas.

Desde el Sur/los Sures, yendo más allá del “universalismo de datos”… y del universalismo de la teoría social

Creemos que necesitamos sistematizar y entablar un diálogo sistemático con tradiciones, epistemologías y experiencias que deconstruyen el dominio de los enfoques occidentales aplicados a la dataficación, y que no reconocen la pluralidad, la diversidad y la riqueza cultural del Sur/de los Sures (ver Herrera, Sierra y del Valle 2016). Al igual que Anita Say Chan (2013), nosotros y nosotras sentimos que demasiados enfoques críticos siguen dependiendo de una especie de “universalismo digital” que tiende a asimilar la heterogeneidad de los diversos contextos así como a pasar por alto las diferencias y las especificidades culturales. En este sentido, queremos contribuir a la conversación en curso sobre la urgencia de una “teoría del sur” que “cuestione el universalismo en el campo de la teoría social”. Nos unimos a Payal Arora al afirmar que “necesitamos un estudio concertado y sostenido sobre el papel y el impacto de los ‘big data’ en el Sur Global” (2016: 1693), y damos un paso más allá, ampliando el espectro para incluir a todos los Sures, en plural, que habitan en nuestro universo cada vez más complejo.

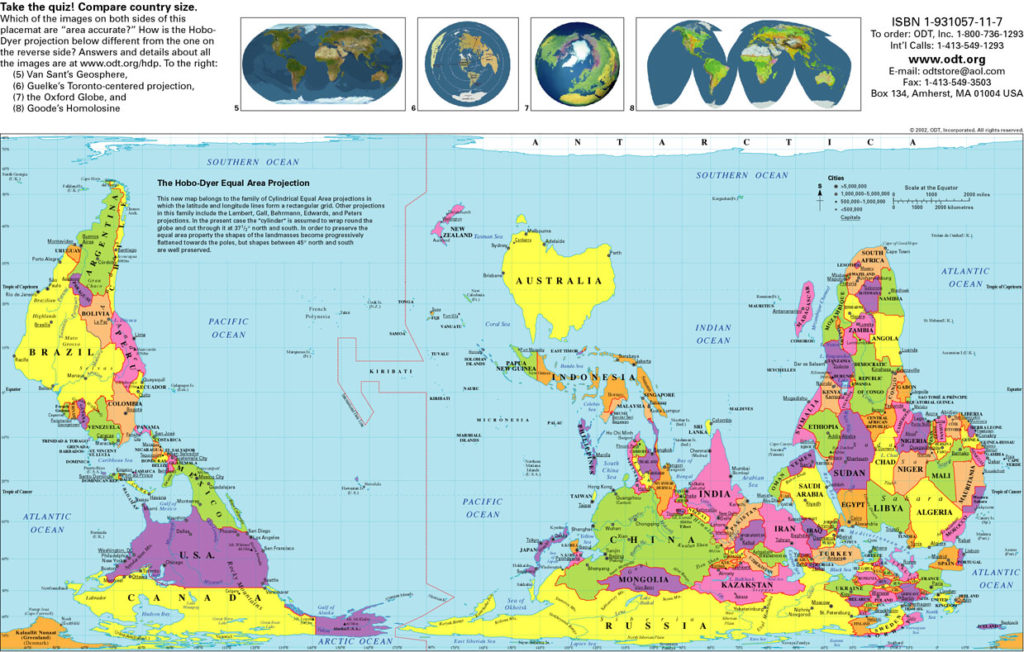

Como nos recordaron Arora (2016) y Udupa (2015), mientras que la mayoría de la población mundial reside fuera de Occidente, seguimos encuadrando debates clave sobre la vigilancia de la democracia –así como las demandas planteadas por modelos y prácticas alternativos— a través de los programas, preocupaciones, contextos, comportamientos y teorías occidentales. Y aunque reconocemos las contribuciones de muchos/as de nuestros/as colegas (y pedimos disculpas si por razones de brevedad no hemos podido incluiros a todos/todas), sentimos que falta algo en la conversación y que solo un esfuerzo colectivo, a través de disciplinas, lenguas y áreas de investigación, puede ayudarnos a considerar los “big data” desde el Sur. Nuestra definición del Sur es flexible y expansiva, inspirada en los escritos del sociólogo Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2007 y 2014), uno de los autores que con más urgencia han subrayado la necesidad de las epistemologías del Sur frente al “epistemicidio” del neoliberalismo. En primer lugar, está el Sur geográfico, es decir, las personas, las actividades, las políticas y las tecnologías que surgen literalmente en los márgenes del mundo, tal como se presentan en el mapa de Mercator. En segundo lugar, y más importante, nuestro Sur es un lugar de resistencia, subversión y creatividad. Podemos encontrar innumerables Sures también en el “norte global”, siempre que haya resistencia a la injusticia y luchas por mejorar las condiciones de vida frente al “capitalismo de datos”.

Nuestras reflexiones sobre los “big data desde el Sur” encajan –y esperan alimentar— el proceso más amplio de reposicionamiento epistemológico de las ciencias sociales. Creemos que no podemos evitar medir las dinámicas sociotécnicas de la dataficación frente a “los procesos históricos de despojo, esclavización, apropiación y extracción […] centrales para la aparición del mundo moderno” (Bhambra y de Sousa Santos 2017: 9), con el riesgo de volver a cometer los mismos errores, y lo mismo se puede decir de nuestra caja de herramientas disciplinarias. Como nos recuerdan Bhambra y de Sousa Santos, “si las injusticias del pasado continúan en el presente y necesitan reparación, ese trabajo reparativo también debe extenderse a la estructura disciplinaria que oscurece tanto como ilumina el camino adelante” (ibid.).

¿Qué implicaría entonces una teoría sureña de los “big data”?

Aceptamos el desafío de Say Chan (2013), que nos recordó que hay formas diferentes de las convencionales para imaginar la relación entre la tecnología y las personas. Aquí compartimos nuestra creciente lista de las condiciones sine-qua-non para pensar la dataficación del Sur. El listado es un trabajo en progreso y viene con una invitación explícita a unirse a nosotros y nosotras en este ejercicio.

- Llevar a la agencia en el centro de la observación de los mecanismos y prácticas de abajo hacia arriba y de arriba hacia abajo. Inspirándonos en Barbero (1987), debemos centrarnos en la resistencia y la heterogeneidad de las prácticas en lo que se refiere a la dataficación: no solo en los datos en sí, sino también en su infraestructura y dinámicas.

- Descolonizar nuestro pensamiento y situar la dinámica post-Snowden del capitalismo de datos en las especificidades del Sur. Si bien muchos elementos serán los mismos, las implementaciones, los entendimientos y las consecuencias pueden ser diferentes. Lo que sabemos no debe darse por sentado, sino que hay que descifrarlo críticamente.

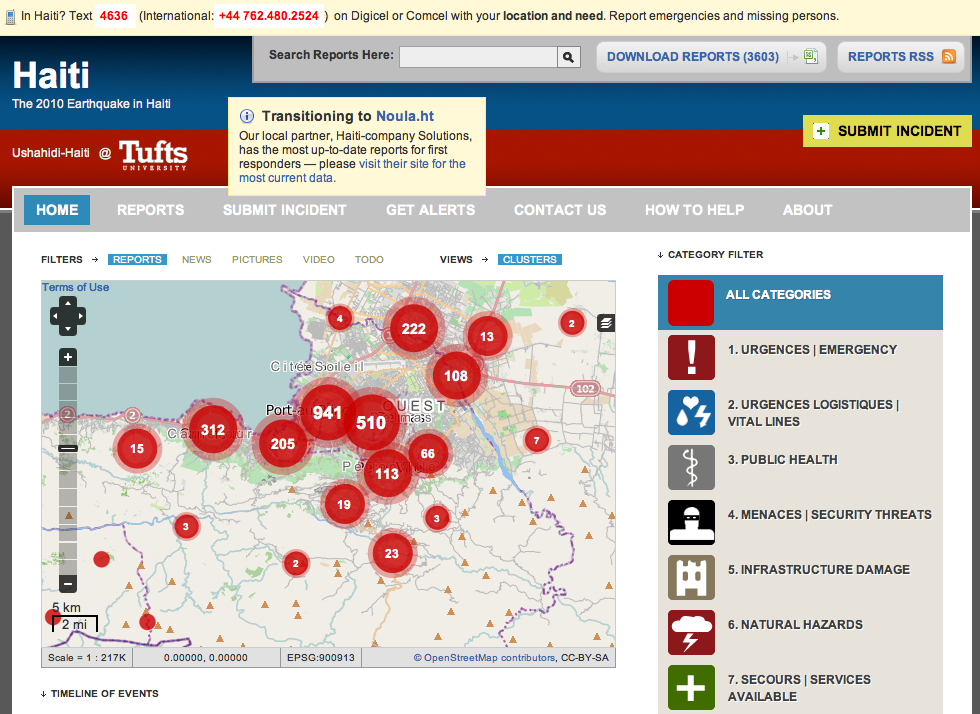

- Prestar atención a las “alternativas”: prácticas alternativas, imaginarios alternativos, epistemologías alternativas, metodologías alternativas en relación con la adopción, uso y apropiación de los big data. Hay que abrirse a lo inesperado y lo inexplorado. Y para aclarar las cosas cabe señalar que las alternativas no son necesariamente subalternas sino simplemente distintas.

- Llevar la infraestructura en serio, desvelando los complejos flujos (de relaciones, datos, poder, dinero y conteo/contabilidad) que ellas abrigan, generan, modelan y promueven (gracias a Anders Fagerjord por la inspiración para pensar en flujos). Situar nociones como la de plataforma en la experiencia vivida en distintas geografías.

- Conectar las epistemologías críticas de los mundos sociales emergentes con la política crítica del cambio social. Gracias a Nick Couldry por compartir sus pensamientos sobre este asunto en Cartagena. Su nuevo libro con Ulisses Mejias sobre “Datos, capitalismo y descolonización de Internet” habla precisamente de esto.

- Ser atento/a y crítico/a con los conceptos y métodos centrados en Occidente. Si bien ofrecen un punto de partida clave, no pueden tomarse por defecto como punto de llegada único para acercarse a los big data del Sur.

- Ser críticos/as con los razonamientos que llegan del Sur también, para evitar caer en el supuesto de que son formas de conocimiento intrínsecamente diferentes, alternativas o incluso mejores y más puras.

- Abrirse al diálogo en la dirección que nos lleve: Norte-Sur, Sur-Sur, Sur-Norte. Frente a mucha complejidad, solo podemos avanzar juntos/as, entrando en un diálogo con distintas epistemologías y enfoques.

Dicho esto, quisiéramos alentar a nuestros/as colegas para que adopten de manera más explícita una perspectiva de economía política, lo que puede ayudarnos a examinar críticamente las múltiples formas de dominación que reproducen y perpetúan la desigualdad, la discriminación y la injusticia a todos los niveles. También abogamos por enfoques históricos capaces de rastrear el despliegue actual de la dataficación a sus raíces en las prácticas coloniales (ver Arora 2016). Proponemos involucrarse con las críticas y las ideas feministas en torno a la descolonización de la tecnología. Finalmente, nos gusta pensar que este tipo de investigación es intrínsecamente “comprometida”: al adoptar los estándares de una sólida investigación científica, la “investigación comprometida” puede tomar partido y, lo más importante, está diseñada para cambiar las cosas en las comunidades con las que nos ponemos en contacto (Milán 2010). Este enfoque va de la mano de la promoción de la alfabetización y la educomunicación crítica, mediante las cuales los académicos buscan que la información sea accesible mediante su traducción a un material comprensible y procesable, con el objetivo de atraer a más personas para luchar por los derechos digitales.

Un ejemplo de acercamiento a los “big data” del Sur

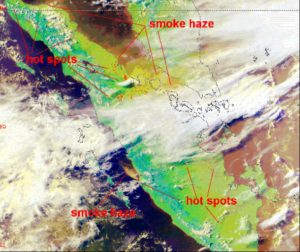

Para hacer que nuestro llamado sea más concreto, ofrecemos el ejemplo de nuestro propio trabajo como una de las muchas maneras posibles de voltear la dataficación boca abajo. Emiliano ha estado estudiando la fabricación algorítmica del consentimiento y la obstaculización de la disidencia en línea, y ha esbozado cómo se forjan formas creativas e innovadoras de resistencia algorítmica en América Latina y más allá (Treré 2016). Stefania y su equipo han estado analizando cómo el activismo de datos (Milán y Gutiérrez 2015; Milán 2017), las nuevas epistemologías de datos (Milán y van der Velden 2016) y las prácticas de resistencia a la recopilación masiva de datos, surgen al margen del “capitalismo de vigilancia”, incluido, por ejemplo, en la región amazónica (Gutiérrez y Milán 2017). Pero necesitamos colectivamente, contigo, dar un paso adelante y repensar también la teoría, más allá de los estudios de caso y los ejemplos. Somos muchos/as en este esfuerzo, ya que nos aupamos a hombros de gigantes. Por nombrar solo a uno de los que inspiró nuestro evento en Cartagena: Hace casi treinta años, el comunicólogo hispano-colombiano Jesús Martín-Barbero nos urgió a pasar “de los medios a las mediaciones”, es decir, de los análisis funcionalistas centrados en los medios a la exploración de las prácticas cotidianas de apropiación de los medios a través de las cuales se promulga resistencia a la dominación y la hegemonía (1987). La poderosa transición que activó fue inherentemente política: significó reorientar nuestra mirada desde las instituciones de los medios hacia las personas y sus culturas heterogéneas para ver cómo se generaba la comunicación en bares, gimnasios, mercados, plazas, familias, etc. Siguiendo a Barbero, nuestro trabajo ha estado orientado a pasar de la dataficación al activismo de datos, examinando las diversas formas en que la ciudadanía y la sociedad civil organizada en el Sur participan en prácticas relacionadas con los datos desde abajo para el cambio social y resisten una dataficación que aumenta la opresión y la desigualdad.

Mucho más queda por hacer y muchas conversaciones por celebrar. Junto con Anita Say Chan, estamos lanzando ‘Big Data from the South’, una red de académicos, académicas y profesionales interesados/as en llevar adelante este diálogo multidisciplinario y multilingüe. ¡Únete a nosotros y nosotras!

Únete a la lista de correo

Lee la convocatoria de “Big Data from the South” (Cartagena, 15 de julio de 2017)

Echa un vistazo al blog dedicado. Atención: ¡incluso hemos encargado un logotipo! Tenemos previsto comenzar pronto a publicar textos de invitados e invitadas sobre el tema. Estamos buscando tus ideas y provocaciones. Para contribuir, envía un correo electrónico a: TrereE@cardiff.ac.uk y s.milan@uva.nl.

Acerca del autor y la autora (y situando al privilegio blanco)

Un investigador y una investigadora que movilizan la interdisciplinariedad para moverse entre el estudio de la sociedad y sus imaginaciones y tácticas tecnológicas: el movimiento, el cambio y el contraste han estado en el centro de nuestras trayectorias académicas y nuestras identidades. Europeos del Sur emigrados al Norte debido al malestar eterno que aqueja el sistema de investigación italiano, nos gusta vernos como investigadores comprometidos que mezclan las aguas entre disciplinas y métodos.

Stefania es Profesora Asociada de Nuevos Medios y Culturas Digitales de la Universidad de Ámsterdam, y está afiliada también a la Universidad de Oslo. Es Investigadora Principal del proyecto DATACTIVE. Emiliano es Lecturer de la Escuela de Periodismo, Medios y Estudios Culturales de la Universidad de Cardiff, donde también es miembro del Data Justice Lab y Research Fellow del Centro de Estudios de Movimientos Sociales COSMOS (Italia). Anteriormente, fue Profesor Asociado en la Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, México.

Ambos hemos investigado y trabajado con varias responsabilidades en varios contextos del Sur. Somos conscientes de escribir desde un lugar privilegiado, pero varios Sures han cruzado nuestras vidas desde el punto de vista profesional y personal, inculcando curiosidad, imponiendo desafíos y sufrimiento ocasional, y obligándonos a realizar preguntas críticas. No tenemos muchas respuestas. Más bien, deseamos que este comentario sea el comienzo de una conversación y de una red abierta y colaborativa en la que diferentes Sures puedan dialogar, aprender y enriquecerse mutuamente.

* El evento fue posible gracias a la financiación del DATACTIVE/European Research Council y al generoso compromiso de Guillén Torres (DATACTIVE) y la Fundación Karisma (Bogotá). También agradecemos la hospitalidad del comité organizador local de IAMCR (y a Amparo Cadavid de UNIMINUTO en particular).

In November 20-30 Stefania will be in Santiago de Chile for a number of talks. She will keynote at the 5th International Symposium of the Red Latinoamericana de Etudios en Vigilancia, Technología y Sociedad, organised by Universidad de Chile with the non-governmental organization Datos Protegidos, whose theme this year is Vigilancia, Democracia y Privacidad en América Latina: vulnerabilidades y resistencias.

In November 20-30 Stefania will be in Santiago de Chile for a number of talks. She will keynote at the 5th International Symposium of the Red Latinoamericana de Etudios en Vigilancia, Technología y Sociedad, organised by Universidad de Chile with the non-governmental organization Datos Protegidos, whose theme this year is Vigilancia, Democracia y Privacidad en América Latina: vulnerabilidades y resistencias.