Author Monika Halkort

In this twofold blogpost (2/2), guest author Monika Halkort complicates the notion of ‘data colonialism’ as employed in The Cost of Connection by Nick Couldry & Ulises Mejias (2019a), drawing on a case study of early datafication practices in historical Palestine. This blogpost is the last out of two: the first contextualizes ‘the colonial’ in data colonialism, the second draws on the casestudy to argue for the need to reimagine data agency in times of data colonialism. Read the first post here.

In the previous blogpost I argued for historically situated study of data colonialism to highlight the intersectionality of its effects. In my work on data relations in the historical experience of Palestinians I draw on modern property, census practices and map making rationalities to achieve that. These examples demonstrate the profound ontological violence involved in projecting the bi-polar structure of European Cartesian thinking upon non-European people and places.

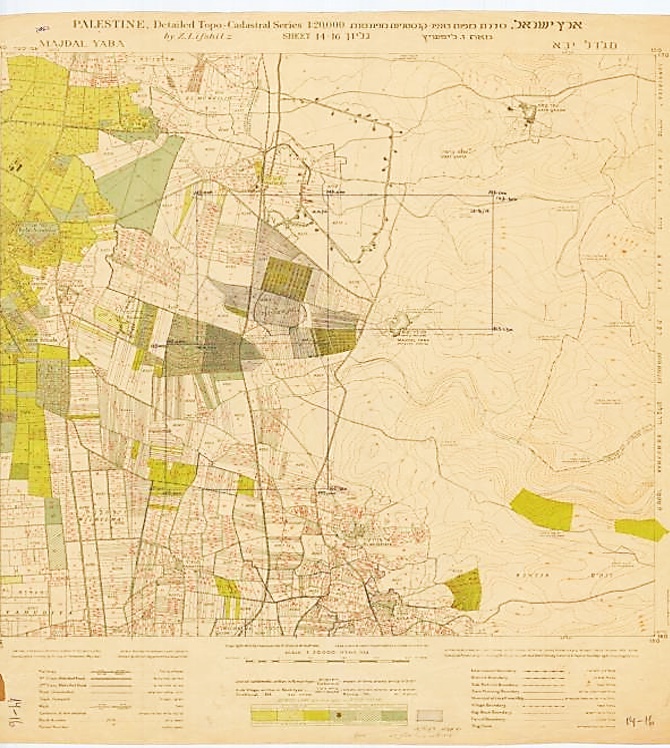

The Ottoman government had never conducted a comprehensive land survey up until the arrival of colonial explorers in the mid 19th century. The census, the cadaster and maps in this sense can be understood as the first wave of datafication in the history of Palestinians. Taken together they provided the key political technologies for dispossessing commonly held grazing grounds and agricultural resources, paving the way for the subsequent transfer of land to Zionist settlers long before the foundation of the state of Israel (Halkort, 2016; 2019). The combined impact of calculating, measuring and reclassifying social and spatial identities and relations systematically disaggregated shared ownership and use rights into exclusivist title deeds and data units, which facilitated the radical reterritorialization of spaces and bodies on the basis of abstract universals – race, class, colonial citizenship and religion – and rendered the lived and embodied topology of social contracts and obligations unintelligible and hence obsolete. As McRae (1993, p. 345) writes, the new techniques of surveying land reconstructed rights as something that could be clearly and objectively measured and determined, in a manner which precluded competing, loosely held customary claims.

The double movement of reterritorialization and enclosure conscripted the population into an ongoing process of self-measuring activity in which the political recognition of aspiring national subjects became ever more dependent on their social separability as property owners, on terms and conditions that were themselves racially marked. It’s in this sense, I conclude, that the accumulative impact of property, census and the map, enabled colonial data infrastructures to function as powerful ontological machines that fundamentally transformed the conditions for articulating and affirming the historical existence and claims of the Palestinian people – not through the use of force, but rather through the “self organizing” principles of the free market competition that brought race, class, religion, property and gender to fold into each other such that they provided a self-generating axes along which shared life unfolds.

Against his backdrop, it becomes possible to see that the violence of dispossession of both modern-colonial and contemporary data regimes, is not reducible to the unfettered capitalization of life without limit, nor to the totalizing structure of social control and ubiquitous surveillance data extraction enrolls. It rather lies in the attempt to enclose the very ‘substance’ of life as central object of political strategy and commodification (Foucault), while successfully concealing how this “substance” is configured alongside binary distinctions – i.e. space and society, data and subjects, nature and politics as the central organizing principle of social and political subjectivities in liberal-capitalist democracies. In other words, what is dispossessed in data relations, are not pre-existing social entities and relations, but rather the very capacity of enacting and sustaining world-building relations that constitute collective life. The violence of data extraction, in this sense, never works on self-enclosed, autonomous bodies or acquired resources but rather through the flexible (re)assemblage of human and non-human entities into transversal arrangements that variously disposition people and things in relation to things of value that help stabilize Cartesian dualisms by foreclosing other ways of being and becoming in the world.

This capacity to affect life not only as it is already given, but its very becoming calls for an uncompromising revision of the techno-political heuristic that currently defines data policy and practice. Such a revision needs to start with a radical re-conception of data agency as the lived and embodied potentiality of materializing relations that implicate data into dynamics of struggle across platforms, operational divisions and scalar domains. Such an idea of data agency is not necessarily empowering, much less confined to human ambitions and concerns. What is gained, however, by rethinking data agency as such a transversal, multi-species arrangement, is that it successfully disrupts the seamless naturalization of data into an ownerless, self-enclosed, and ontologically distinct resource or mere by-product of social activity and relations to make room for acknowledging data as inextricably bound up with the lived and embodied infrastructure of collective life making, and, hence, as inseparable from the ethico-political substance it configures and performs.

About Monika Halkort

Monika Halkort is Assistant Professor of Digital Media and Social Communication at the Lebanese American University in Beirut. Her work traverses the fields of feminist STS, political ecology and post-humanist thinking to unpack the intersectional dynamics of racialization, de-humanisation and enclosure in contemporary data regimes. Her most recent project looks at the new patterns of bio-legitimacy that emerge from the ever denser convergence of social, biological and machine intelligence in environmental sensing and Earth Observation. Taking the Mediterranean sea as her prime example she unpacks how conflicting models of risk and premature death in data recalibrate ‘zones of being’ and ‘non-being’ (Fanon), opening up new platforms of oppression, alienation and ontological displacement that have been characteristic of modern coloniality.

References

Braidotti, Rosi. (2016). Posthuman Critical Theory. In D. Banerji, M. R. Paranjape (eds.), Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures (pp. 13–32). e-book: Springer India. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019a). The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019b). Data Colonialism: Rethinking Big Data’s Relation to the Contemporary Subject. Television and New Media, 1 -14.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019c). The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from Colonised by Data: https://colonizedbydata.com/

Halkort, M. (forthcoming) ‘Dying in the Technosphere. An intersectional analysis of Migration Crisis Maps’, in Specht, D. Mapping Crisis, London Consortium for Human Rights, University of London, London, UK

Halkort, M. (2019). Decolonizing Data Relations: On the moral economy of Data Sharing in a Palestinian Refugee Camp. Canadian Journal of Communication , 317-329.

Halkort, M. (2016) ‘Liquefying Social Capital. The Bio-politics of Digital Circulation in a Palestinian Refugee Camp’, in Tecnoscienza, Nr. 13, 7(2)

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 240-270.

Mbebe, A. (2017). Critique of Black Reason. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

McRae, Andrew. (1993). To know one’s own: Estate surveying and the representation of the land in early modern England. The Huntington Library Quarterly, 56(4), 333–57. doi: 10.2307/3817581

Mignolo, W. (2009). Coloniality: The darker side of modernity. In S. Breitwieser (Hrsg.), Modernologies. Contemporary artists researching modernity and modernism (S. 39 – 49). Barcelona: MACBA.

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 168-178.