Author: Charlotte Ryan (University of Massachusetts, Lowell/Movement-Media

Research Action Project), member of the DATACTIVE ethics board.

This is a response post to the blog ‘Tech, data and social change: A plea for cross-disciplinary engagement, historical memory, and … Critical Community Studies‘ written by Kersti Wissenbach.

To maximize technologies’ value in social change efforts, Kersti Wissenbach urges researchers to join with communities facing power inequalities to draw lessons from practice. In short, the liberating potential of technologies for social change cannot be realized without holistically addressing broader inequalities. Her insights are many, in fact, communication activists and scholars could use her blog as a guide for ongoing conversations. Three points especially resonate with my experiences as a social movement scholar/activist working in collaboration with communities and other scholars:

- Who is at the table?

Wissenbach stresses the critical role of proactive communities in fostering technologies for social change as a corrective to the “dominant civic tech discourse [that] seems to keep departing from the ‘tech’ rather than the ‘civic’.” She stresses that an inclusive “we” emerges from intentional and sustained working relationships. - Power (and inequalities of power) matter!

Acknowledging that technologies’ possibilities are often shaped long before many constituencies are invited to participate, Wissenbach asks those advancing social change technologies to notice the creation and recreation of power structures:

“Only inclusive communities,” she cautions, “can really translate inclusive technology approaches, and consequently, inclusive governance.” - Tech for social change needs critical community studies

Wissenbach calls for the emergence of critical community studies that—as do critical development, communication, feminist, and subaltern studies–crosses disciplines, “taking the community as an entry point in the study of technology for social change.” Practitioners and scholars would reflect together to draw and disseminate shared lessons from experience. This would allow “communities, supposed to benefit from certain decisions, [to] have a seat on the table.”

Anyone interested in the potential of civic tech—activists, scholar-activists, engineers, designers, artists, or other social communication innovators—will warmly welcome Wissenbach’s vision of Critical Community Studies. She proposes not another sub-specialty with esoteric journals and self-referential jargon, but a research network of learning communities expanding conceptual dialogs across the usual divides. And, she recognizes the urgent need to preserve and broadly disseminate learning about technologies for social change.

I agree but cautiously. It is just what’s needed. But the academy tends to resist engaged scholarship. We need to think about where to locate transformative theory-building; sadly, calls to break with traditional research approaches may be more warmly received outside academic institutions than within. The academy itself, at least in the United States, is under duress. How would Critical Community Studies explain itself to academic institutions fascinated by brand, market niche, and revenue streams? Critical Community Studies is not likely to be a cash cow generating more profits faster, and with less investment. The U.S. trend to turn education into a profit-making industry may be extreme, but it raises the need to look before we leap.

Like Wissenbach, I entered the academy with deep roots in social movements and community activism. Like her, I want the academy to produce knowledge and technology for the social good. Like her, I want communities directly affected to be fully vested in all phases of learning. Like her, I am eager to move beyond vague calls for participation and inclusion. My experiences to date, however, give me pause for thought.

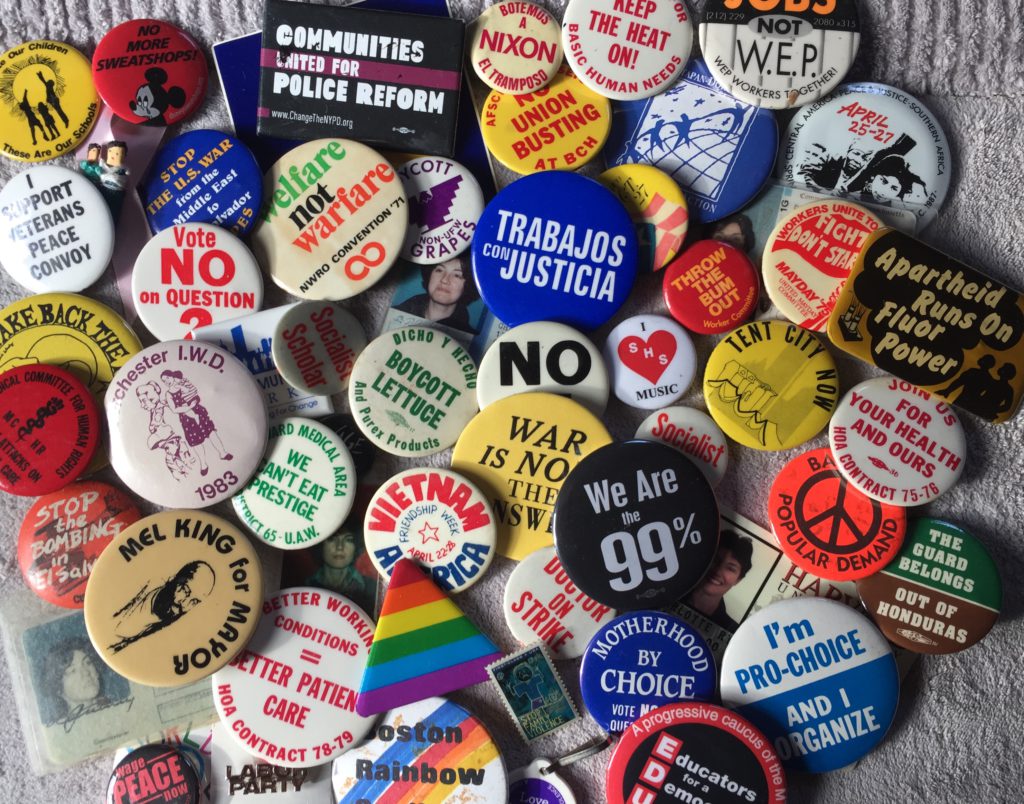

Caption: Thirty years in buttons

In the mid-1980’s, I was among a dozen established and emerging scholars who formed the university-based Media Research Action Project (MRAP). We were well-positioned to bridge the theorist-practitioner divide; many of us had begun as movement activists and we had ties to practitioners. This made it easier for MRAP to work with under-represented and misrepresented communities and constituencies to identify and challenge barriers to democratic communication and to build communication capacity.

U.S. based social movements face recurring challenges: our movements hemorrhage learning between generations; we still need to grapple with the legacies of slavery, colonialism and jingoism; our labor movement has withered. Living amidst relative plenty, U.S. residents may feel far removed from crises elsewhere. Competitive individualism, market pressures, and dismantled social welfare programs leave U.S. residents feeling precarious —even if we embrace liberatory ideals.

In light of these material conditions, MRAP wanted to broaden political dialogs about equality and justice. At first, we focused on transferring communication skills—one and two-day workshops. We soon realized that we needed ongoing working relationships to test strategies, build infrastructure and shared conceptual frameworks. But it took years to find the funds to run a more sustained program. Foundations—even when they liked our work—wanted us to ‘scale up’ fast (one national foundation asked us to take on 14 cities). In contrast, we saw building viable working relations as labor-intensive and slow. One U.S. federal agency offered hefty funding for proposals to “bridge the digital divide.” MRAP filed a book-length application with ten community partner organizations, eight in communities of color. The agency responded positively to MRAP’s plan, they urged us to resubmit but asked that we dump our partners and replace them with mainstream charities, preferably statewide.

And so the constraints tightened. Government and foundations’ preference for quick gains could marginalize (again) the very partners MRAP formed to support. To support ourselves, we could take day jobs, but this limited our availability. Over and over, we found—at least in the U.S. context—talk of addressing power inequalities far exceeded public will and deeds. Few mainstream institutions would commit the labor, skill, and time to reduce institutionalized power inequalities. Nor did they appreciate that developing shared lessons from practical experiences is labor intensive. (Wissenbach notes a number of these obstacles).

Despite all of the above, MRAP and our partners had victories. One neighborhood collaboration took over local political offices; another defeated an attempt to shut down an important community school; others passed legislation; and made common cause with the Occupy Movement to challenge the demonization of poor people in America. We won…sometimes. More often, we lost but lived to fight another day. And we helped document the ups and downs of our social movements. It was enormous fun even when it was really hard. As the designated holders and tellers of these histories, MRAP participants deepened our understanding of the macro-mezzo-micro interplay of political, social, economic, and cultural power.

From hundreds of conversations, dozens of collaborations, and gigabytes of notes, case studies, and foundation proposals, came a handful of collaborations that advanced our understanding of how U.S. movement organizations synchronize communication, political strategizing, coalition building, and leader and organizational development, and how groups integrate learning into ongoing campaigns.

We have begun to upload MRAP’s work at www.mrap.info. But those pursuing a transformed critical research tradition, should acknowledge that the academy has resisted grounded practice, and that the best critical reflections were often led by activists outside the academy rooted in communities directly facing power inequalities. In light of this, Wissenbach’s insistence that communities directly affected “be at the table” becomes an absolute.

Let me turn to Critical Communication Studies more specifically. To maximize publishing, U.S. scholars tend to communicate within, not across, disciplines. Anxious regarding slowing their productivity, they tend to avoid the unpredictability of practical work. For their part, the civic tech networks and communities facing inequalities find themselves competing for resources, a competition that can undermine the very collaborations they want to build. Even if resources are located, efforts may fade if a grant ends or a government changes hands.

So while I welcome the call for researchers to join practitioners in designing mutually beneficial projects, I want to do it right and that may mean do it slow. First off, who is the “we/us” mentioned twenty times by Wissenbach (or an equal number of times by me)? We need a real “we”: transforming institutional practices and priorities whether in academic or communication systems is a collective process. An aggregate of individuals even if they share common values does not constitute “us,” social movements as dialogic communities that consider, test, and unite around strategies. (As Wissenbach underscores, “we” need to shift power, and this requires shared strategies, efficient use of sustainable resources, and a capacity to learn from experience).

In short, transforming scholarly research from individual to collective models will take movement building. A first step may be recognizing that “we” needs to be built. Calling “we” a social construction does not mean it’s unreal; it means it’s our job to make it real.

Conclusion

I share Wissenbach’s respect for past and present efforts to lessen social inequalities via communication empowerment. I agree that “only inclusive communities can really translate inclusive technology approaches and, consequently, inclusive governance.” And I know that this will be hard to achieve. Progress may lie ahead but precarity and heavy work lie ahead as well. A beloved friend says to me these days, “Getting old is not for the faint of heart.” Neither is movement building.

Bibliography:

Howley, K. (2005). Community media: people, places, and communication technologies. Cambridge, UK ; New York : Cambridge University Press.

Kavada, A. (2010). Email lists and participatory democracy in the European social forum. Media, Culture & Society, 32(3), 355. doi: 10.1080/13691180802304854

Kavada, A. (2013). Internet cultures and protest movements: The cultural links between strategy, organizing and online communication. In B. Cammaerts, A. Mattoni & P.

McCurdy (Eds.), Mediation and protest movements (pp. 75–94). Bristol, England: Intellect.

Kidd, D., Barker-Plummer, B., & Rodriguez, C. (2005). Media democracy from the ground up: mapping communication practices in the counter public sphere. Report to the Social Science Research Council. New York

Kidd, D., Rodriguez, C., & Stein, L. (2009). Making our media: Global initiatives toward a democratic public sphere. Cresskill: Hampton Press.

Lentz, R. G., & Oden, M. D. (2001). Digital divide or digital opportunity in the Mississippi Delta region of the US. Telecommunications policy, 25(5), 291-313.

Lentz, R. G. Regulation as Linguistic Engineering. (2011). The Handbook of Global Media and Communication Policy, 432-448. IN Mansell, R., & Raboy, M. (Eds.) (Vol. 6). John Wiley & Sons.

Magallanes-Blanco, C., & Pérez-Bermúdez, J. A. (2009). Citizens’ publications that empower: social change for the homeless. Development in practice, 19(4-5), 654-664.

Mattoni, A. (2016). Media practices and protest politics: How precarious workers mobilise. Routledge.

Mattoni, A., & Treré, E. (2014). Media practices, mediation processes, and mediatization in the study of social movements. Communication theory, 24(3), 252-271.

Milan, S. (2009). Four steps to community media as a development tool. Development in Practice, 19(4-5), 598-609.

Rubin, N. (2002). Highlander media justice gathering final report. New Market, TN: Highlander Research and Education Center.

Treré, E. and Magallanes-Blanco, C. (2015) Battlefields, Experiences, Debates: Latin American Struggles and Digital Media Resistance, International Journal of Communication 9: 3652–366.