This invited blog post originally appeared in the forum ‘Cloud Communities: The Dawn of Global Citizenship?’ of the GLOBALCIT project (European University Institute). It is part of an interesting multidisciplinary conversation accessible from the GLOBALCIT website. I wish to thank Rainer Baubock and Liav Orgad for the invitation to contribute to the debate.

Cloud communities and the materiality of the digital

By Stefania Milan (University of Amsterdam)

As a digital sociologist, I have always found ‘classical’ political scientists and lawyers a tad too reluctant to embrace the idea that digital technology is a game changer in so many respects. In the debate spurred by Liav Orgad’s provocative thoughts on blockchain-enabled cloud communities, I am particularly fascinated by the tension between techno-utopianism on the one hand (above all, Orgad and Primavera De Filippi), and socio-legal realism on the other (e.g., Rainer Bauböck, Michael Blake, Lea Ypi, Jelena Dzankic, Dimitry Kochenov). I find myself somewhere in the middle. In what follows, I take a sociological perspective to explain why there is something profoundly interesting in the notion of cloud communities, why however little of it is really new, and why the obstacles ahead are bigger than we might like to think. The point of departure for my considerations is a number of experiences in the realm of transnational social movements and governance: what we can learn from existing experiments that might help us contextualize and rethink cloud communities?

Three problems with Orgad’s argument

To start with, while I sympathise with Orgad’s provocative claims, I cannot but notice that what he deems new in cloud communities—namely the global dimension of political membership and its networked nature—is indeed rather old. Since the 1990s, transnational social movements for global justice have offered non-territorial forms of political membership—not unlike those described as cloud communities. Similar to cloud communities, these movements were the manifestation of political communities based on consent, gathered around shared interests and only minimally rooted in physical territories corresponding to nation states (see, e.g., Tarrow, 2005). In the fall of 2011 I observed with earnest interest the emergence of yet another global wave of contention: the so-called Occupy mobilisation. As a sociologist of the web, I set off in search for a good metaphor to capture the evolution of organised collective action in the age of social media, and the obvious candidate was… the cloud. In a series of articles (see, for example, here and here) and book chapters (e.g., here and here), I developed my theory of ‘cloud protesting’, intended to capture how the algorithmic environment of social media alters the dynamics of organized collective action. In light of my empirical work, I agree with Bauböck, who acknowledges that cloud communities might have something to do with the “expansion of civil society, of international organizations, or of traditional territorial polities into cyberspace”. He also points out how, sadly, people can express their political views – and, I would add, engage in disruptive actions, as happens at some fringes of the movement for global justice – only because “a secure territorial citizenship” protects their exercise of fundamental rights, such as freedom of expression and association. Hence the questions a sociologist might ask: do we really need the blockchain to enable the emergence of cloud communities? If, as I argue, the existence of “international legal personas” is not a pre-requisite for the establishment of cloud communities, what would the creation of “international legal personas” add to the picture?[1]

Secondly, while I understand why a blockchain-enabled citizenship system would make life easier for the many who do not have access to a regular passport, I am wary of its “institutionalisation”, on account of the probable discrepancies between the ideas (and the mechanisms) associated with a Westphalian state and those of politically active activists and radical technologists alike. On the one hand, citizens interested in “advanced” forms of political participation (e.g., governance and the making of law) might not necessarily be inclined to form a state-like entity. For example, many accounts of the so-called “movement for global justice” (McDonald, 2006; della Porta & Tarrow, 2005) show how “official” membership and affiliation is often not required, not expected and especially not considered desirable. Activism today is characterised by a dislike and distrust of the state, and a tendency to privilege flexible, multiple identities (e.g., Bennett & Segerberg, 2013; Juris, 2012; Milan, 2013). On the other hand, the “radical technologists” behind the blockchain project are animated by values—an imaginaire (Flichy, 2007)—deeply distinct from that of the state (see, e.g., Reijers & Coeckelbergh, 2018). While the blockchain technology is enabled by a complex constellation of diverse actors, it is legitimate to ask whether it is possible to bend a technology built with an “underlying philosophy of distributed consensus, open source, transparency and community” with the goal to “be highly disruptive”(Walport, 2015)… to serve similar purposes as those of states?

Thirdly, Orgad’s argument falls short of a clear description of what the ‘cloud’ stands for in his notion of cloud communities. When thinking about ‘clouds’, as a metaphor and a technical term, we cannot but think of cloud computing, a “key force in the changing international political economy” (Mosco, 2014, p. 1) of our times, which entails a process of centralisation of software and hardware allowing users to reduce costs by sharing resources. The cloud metaphor, I argued elsewhere (Milan, 2015), is an apt one as it exposes a fundamental ambivalence of contemporary processes of “socio-legal decentralisation”. While claiming distance from the values and dynamics of the neoliberal state, a project of building blockchain-enabled communities still relies on commercially-owned infrastructure to function.

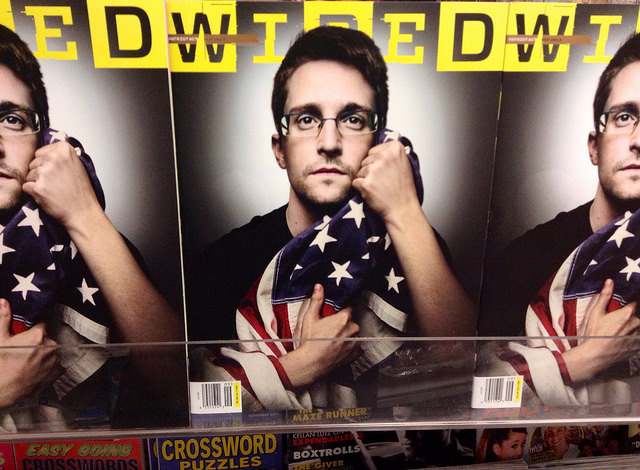

Precisely to reflect on this ambiguity, my most recent text on cloud protesting interrogates the materiality of the cloud. We have long lived in the illusion that the internet was a space free of geography. Yet, as IR scholar Ron Deibert argued, “physical geography is an essential component of cyberspace: Where technology is located is as important as what it is” (original italics). The Snowden revelations, to name just one, have brought to the forefront the role of the national state in—openly or covertly—setting the rules of user interactions online. What’s more, we no longer can blame the state alone, but the “surveillant assemblage” of state and corporations (Murakami Wood, 2013). To me, the big absent in this debate is the private sector and corporate capital. De Filippi briefly mentioned how the “new communities of kinship” are anchored in “a variety of online platforms”. However, what Orgav’s and partially also Bauböck’s contributions underscore is the extent to which intermediation by private actors stands in the way of creating a real alternative to the state—or at least the fulfilment of certain dreams of autonomy, best represented today by the fascination for blockchain technology. Bauböck rightly notes that “state and corporations… will find ways to instrumentalise or hijack cloud communities for their own purposes”. But there is more to that: the infrastructure we use to enable our interpersonal exchanges and, why not, the blockchain, are owned and controlled by private interests subjected to national laws. They are not merely neutral pipes, as Dumbrava reminds us.

Self-governance in practice: A cautionary tale

To be sure, many experiments allow “individuals the option to raise their voice … in territorial communities to which they do not physically belong”, as beautifully put by Francesca Strumia. Internet governance is a case in point. Since the early days of the internet, cyberlibertarian ideals, enshrined for instance in the ‘Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace’ by late JP Barlow, have attributed little to no role to governments—both in deciding the rules for the ‘new’ space as well as the citizenship of its users (read: the right to participate in the space and in the decision-making about the rules governing it). In those early flamboyant narratives, cyberspace was to be a space where users—but really engineers above all—would translate into practice their wildest dreams in matter of self-governance, self-determination and, to some extent, fairness. While cyberlibertarian views have been appropriated by both conservative (anti-state) and progressive forces alike, some of their founding principles have spilled over to real governance mechanisms—above all the governance of standards and protocols by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and the management of the the Domain Name System (DNS) by the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN).[2] Here I focus on the latter, where I have been active for about four years (2014-2017).

ICANN is organized in constituencies of stakeholders, including contracted parties (the ‘middlemen’, that is to say registries and registrars that on a regional base allocate and manage on behalf of ICANN the names and numbers, and whose relationship with ICANN is regulated by contract), non-contracted parties (corporations doing business on the DNS, e.g. content or infrastructure providers) and non-commercial internet users (read: us). ICANN’s proceedings are fully recorded and accessible from its website; its public meetings, thrice a year and rotating around the globe, are open to everyone who wants to walk in. Governments are represented in a sort of United Nations-style entity called the Government Advisory Committee. While corporate interests are well-represented by an array of professional lobbyists, the Non-Commercial Stakeholder Group (NCSG), which stands in for civil society,[3] is a mix and match of advocates of various extraction, expertise and nationality: internet governance academics, nongovernmental organisations promoting freedom of expression, and independent individuals who take an interest in the functioning of the logical layer of the internet.

The 2016 transition of the stewardship over the DNS from the US Congress to the “global multistakeholder community” has achieved a dream unique in its kind, straight out of the cyberlibertarian vision of the early days: the technical oversight of the internet[4] is in the hands of the people who make and use it, and the (advisory) role of the state is marginal. Accountability now rests solely within the community behind ICANN, which envisioned (and is still implementing) a complex system of checks and balances to allow the various stakeholder voices to be fairly represented. No other critical infrastructure is regulated by its own users. To build on Orgad’s reasoning, the community around ICANN is a cloud community, which operates by voluntary association and consensus [5],[5] and is entitled to produce “governance and the creation of law”.[6]

But the system is far from perfect. Let’s look at how the so-called civil society is represented, focusing on one such entity, the NCSG. Firstly, given that everyone can participate, the variety of views represented is enormous, and often hinders the ability of the constituency to be effective in policy negotiations. Yet, the size of the group is relatively small: at the time of writing, the Non-Commercial User Constituency (the bigger one among the two that form the NCSG) comprises “538 members from 161 countries, including 118 noncommercial organizations and 420 individuals”, making it the largest constituency within ICANN: this is nothing when compared to the global internet population it serves, confirming, as Dzankic argues, that “direct democracy is not necessarily conducive to broad participation in decision-making”. Secondly, ICANN policy-making is highly technical and specialised; the learning curve is dramatically steep. Thirdly, to be effective, the amount of time a civil society representative should spend on ICANN is largely incompatible with regular daily jobs; civil society cannot compete with corporate lobbyists. Fourthly, with ICANN meetings rotating across the globe, one needs to be on the road for at least a month per year, with considerable personal and financial costs.[7] In sum, while participation is in principle open to everyone, informed participation has much higher access barriers, which have to do with expertise, time, and financial resources (see, e.g., Milan & Hintz, 2013).

As a result, we observe a number of dangerous distortions of political representation. For example, when only the highly motivated participate, the views and “imaginaries” represented are often at the opposite ends of the spectrum (cf., Milan, 2014). Only the most involved really partake in decision-making, in a mechanism which is well known in sociology: the “tyranny of structurelessness” (Freeman, 1972), which is typical of participatory, consensus-based organising. The extreme personalisation of politics that we observe within civil society at ICANN—a small group of long-term advocates with high personal stakes—yields also another similar mechanism, known as “the tyranny of emotions” (Polletta, 2002), by which the most invested, independently of the suitability of their curricula vitae, end up assuming informal leadership roles—and, as the case of ICANN shows, even in presence of formal and carefully weighted governance structures. Decision-making is thus based on a sort of “microconsensus” within small decision-making cliques (Gastil, 1993).[8] To make things worse, ICANN is increasingly making exceptions to its own, community-established rules, largely under the pressure of corporations as well as law enforcement: for example, the corporation has recently been accused of bypassing consensus policy-making through voluntary agreements ad private contracting.

Why not (yet?): On new divides and bad players

In conclusion, while I value the possibilities the blockchain technology opens for experimentation as much as Primavera De Filippi, I do not believe it will really solve our problems in the short to middle-term. Rather, as it is always with technology because of its inherent political nature (cf., Bijker, Hughes, & Pinch, 2012), new conflicts will emerge—and they will concern both its technical features and its governance.

Earlier contributors to this debate have raised important concerns which are worth listening to. Besides Bauböck’s concerns over the perils for democracy represented by a consensus-based, self-governed model, endorsed also by Blake, I want to echo Lea Ypi’s reminder of the enormous potential for exclusion embedded in technologies, as digital skills (but also income) are not equally distributed across the globe. For the time being, a citizenship model based on blockchain technology would be for the elites only, and would contribute to create new divides and to amplify existing ones. The first fundamental step towards the cloud communities envisioned by Orgad would thus see the state stepping in (once again) and being in charge of creating appropriate data and algorithmic literacy programmes whose scope is out of reach for corporations and the organised civil society alike.

There is more to that, however. The costs to our already fragile ecosystem of the blockchain technology are on the rise along with its popularity. These infrastructures are energy-intensive: talking about the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, tech magazine Motherboard estimated that each transaction consumes 215 Kilowatt-hour of electricity—the equivalent of the weekly consumption of an American household. A world built on blockchain would have a vast environmental footprint (see also Mosco, 2014). Once again, the state might play a role in imposing adequate regulation mindful of the environmental costs of such programs.

But I do not intend to glorify the role of the state. On the contrary, I believe we should also watch out for any attempts by the state to curb innovation. The relatively brief history of digital technology, and even more that of the internet, is awash with examples of late but extremely damaging state interventions. As soon as a given technology performs roles or produces information that are of interest to the state (e.g., interpersonal communications), the state wants to jump in, and often does so in pretty clumsy ways. The recent surveillance scandals have abundantly shown how state powers firmly inhabit the internet (cf., Deibert, 2009; Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski, & Zittrain, 2010; Lyon, 2015)—and, as the Cambridge Analytica case reminds us, so do corporate interests. Moreover, the two are, more often than not, dangerously aligned.

I do not intend, with my cautionary tales, to hinder any imaginative effort to explore the possibilities offered by blockchain to rethink how we understand and practice citizenship today. The case of Estonia shows that different models based on alternative infrastructure are possible, at least on the small scale and in presence of a committed state. As scholars we ought to explore those possibilities. Much work is needed, however, before we can proclaim the blockchain revolution.

References

Bennett, L. W., & Segerberg, A. (2013). The Logic of Connective Action Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Bijker, W. E., Hughes, T. P., & Pinch, T. (Eds.). (2012). The Social Construction of Technological Systems. New Direction in the Sociology and History of Technology. Cambridge, MA and London, England: MIT Press.

Deibert, R. J. (2009). The geopolitics of internet control: censorship, sovereignty, and cyberspace. In A. Chadwick & P. N. Howard (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics (pp. 323–336). London: Routledge.

Deibert, R. J., Palfrey, J. G., Rohozinski, R., & Zittrain, J. (Eds.). (2010). Access Controlled: The Shaping of Power, Rights, and Rule in Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

della Porta, D., & Tarrow, S. (Eds.). (2005). Transnational Protest and Global Activism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Flichy, P. (2007). The internet imaginaire. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Freeman, J. (1972). The Tyranny of Structurelessness.

Gastil, J. (1993). Democracy in Small Groups. Participation, Decision Making & Communication. Philadelphia, PA and Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Juris, J. S. (2012). Reflections on #Occupy Everywhere: Social Media, Public Space, and Emerging Logics of Aggregation. American Ethnologist, 39(2), 259–279.

Lyon, D. (2015). Surveillance After Snowden. Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity Press.

McDonald, K. (2006). Global Movements: Action and Culture. Malden, MA and Oxford: Blackwell.

Milan, S. (2013). WikiLeaks, Anonymous, and the exercise of individuality: Protesting in the cloud. In B. Brevini, A. Hintz, & P. McCurdy (Eds.), Beyond WikiLeaks: Implications for the Future of Communications, Journalism and Society (pp. 191–208). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Milan, S. (2015). When Algorithms Shape Collective Action: Social Media and the Dynamics of Cloud Protesting. Social Media + Society, 1(1).

Milan, S., & Hintz, A. (2013). Networked Collective Action and the Institutionalized Policy Debate: Bringing Cyberactivism to the Policy Arena? Internet & Policy, 5, 7–26.

Milan, S., & ten Oever, N. (2017). Coding and encoding rights in internet infrastructure. Internet Policy Review, 6(1).

Mosco, V. (2014). To the Cloud: Big Data in a Turbulent World. New York: Paradigm Publishers.

Murakami Wood, D. (2013). What Is Global Surveillance?: Towards a Relational Political Economy of the Global Surveillant Assemblage. Geoforum, 49, 317–326.

Polletta, F. (2002). Freedom Is an Endless Meeting: Democracy in American Social Movements. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reijers, W., & Coeckelbergh, M. (2018). The Blockchain as a Narrative Technology: Investigating the Social Ontology and Normative Configurations of Cryptocurrencies. Philosophy & Technology, 31(1), 103–130.

Tarrow, S. (2005). The New Transnational Activism. New York: Cambridge University.

Walport, M. (2015). Distributed Ledger Technology: Beyond blockchain. London: UK Government Office for Science. London: UK Government Office for Science.

Notes:

[1] I am aware that there is a fundamental drawback in social movements when compared to cloud communities: unlike the latter, the former are not rights providers. However, these are the questions one could ask taking a sociological perspective.

[2] The system of unique identifiers of the DNS comprises the so-called “names”, standing in for domain names (e.g., www.eui.eu), and “numbers”, or Internet Protocol (IP) addresses (e.g., the “machine version” of the domain name that a router for example can understand). The DNS can be seen as a sort of “phone book” of the internet.

[3] Technically, of the DNS, which is only a portion of what we call “the internet”, although the most widely used one.

[4] Civil society representation in ICANN is more complex than what is described here. The NCSG is composed of two (litigious) constituencies, namely the Non-Commercial User Constituency (NCUC) and the Non-Profit Operational Concerns (NPOC). In addition, “non-organised” internet users can elect their representatives in the At-Large Advisory Committee (ALAC), organised on a regional basis. The NCSG, however, is the only one who directly contributes to policy-making.

[5] ICANN is both a nonprofit corporation registered under Californian law, and a community of volunteers who set the rules for the management of the logical layer of the internet by consensus. See also the ICANN Bylaws (last updated in August 2017).

[6] This should at least in part address Post’s doubts about the ability of a political community to govern those outside of its jurisdiction. One might argue that internet users are, perhaps unwillingly or simply unconsciously, within the “jurisdiction” of ICANN. I do believe, however, that the case of ICANN is an interesting one for its being in between the two “definitions” of political communities.

[7] ICANN allocates consistent but not sufficient resources to support civil society participation in its policymaking. These include travel bursaries and accommodation costs and fellowship programs for induction of newcomers.

[8] Although a quantitative analysis of the stickiness of participation in relation to discursive change reveals a more nuanced picture (see, for example, Milan & ten Oever, 2017).