In the context of COVID-19, what are the perils involved by the perpetuated subordination of social welfare access to biometric identification?

Gradually over the last years, India has introduced biometric identification of users in most of its social welfare schemes. One of the main such schemes is the Public Distribution System (PDS), the nation’s largest food security programme, which provides rationed subsidised commodities to the nation’s poor through a network of ration shops. Biometric access to the PDS is largely operated through Aadhaar, the world’s largest digital identification scheme which provides enrolees with a 12-digit number and capture of biometric credentials (ten fingerprint and iris scans) for recognition. While modalities of identity identification and authentication differ through the country, states that adopted an Aadhaar-enabled PDS require recipients to authenticate through a biometric point-of-sale machine to receive rations.

As a consequence of the COVID-19 crisis, biometric authentication in ration shops has been suspended in several Indian states. A commonly given reason for this is the risk of disease transmission associated to users’ fingerprint contact with the machine, which falls under the broader remit of social distancing measures taken within the ongoing pandemic. The Indian case epitomises, however, a global trend of transition to biometric identification in anti-poverty programmes, programmes that – in the light of very serious effects of the COVID-19 crisis on vulnerable groups – are now more crucial to their recipients than ever. In the context of COVID-19, what are the perils involved by the perpetuated subordination of social welfare access to biometric identification?

The Trade-Offs of Digital Identity

With reference to the use of biometrics in India’s social welfare system, many researchers have highlighted the dichotomy between an anti-leakage rationale and the exclusionary effects yielded by such technologies. Latest in chronological order, Muralidharan et al. (2020) report on a large-scale experiment conducted in Jharkhand, a state where deaths by starvationdue to failed Aadhaar-enabled authentication of PDS beneficiaries were previously reported. The results of the study reveal a 10 percent reduction in benefits for recipients (23 percent of the total) who had not linked Aadhaar credentials to benefit rolls, with 2.8 percent receiving no benefits at all. Such exclusionary effects mirror previous studies of the Aadhaar-based PDS in the same state, with Drèze et al. (2017) reporting, among others, the anxiety brought in poor people’s lives by the uncertainties of biometrically-enabled foodgrain distribution.

The policy vision behind biometric anti-poverty schemes can be summarised in terms of two different types of error being tackled. In targeted welfare schemes, an exclusion error means the exclusion of genuinely entitled subjects, while an inclusion error indicates the erroneous inclusion of non-entitled subjects into provision. By matching biometric records (collected through databases such as Aadhaar) with records of recipients’ entitlements, biometric anti-poverty schemes promise to maximise the affordance of proper targeting, offering credentials to the excluded and preventing access to the erroneously included. This rationale lies at the basis not only of the global proliferation of digital identity schemes, but of their ever-increasing incorporation in anti-poverty programmes, of which the Aadhaar-enabled Indian system constitutes a notable example.

But the reality revealed by extant research, including our previous work on the Karnataka PDS, differs from the orthodoxy of good targeting. First, as illustrated most recently by Hundal et al. (2020), requiring biometric identification at the ration shop does not prevent diversion, because the system affords recording successful disbursement even if rations are not provided as per eligibility. Second, there is a trade-off between anti-leakage affordances–in the form of accurate recognition at the point of sale–and the repeated exclusions of entitled beneficiaries, for reasons that range from machines’ malfunctioning to issues of fingerprint readability reported to affect, in particular, the elderly and those in manual labour. In the Aadhaar-enabled PDS, the need for multiple fragile technologies to work at the same time, as highlighted by Jean Drèze, poses a problem of practical feasibility of the system, which is crucial to those parts of the country that are most subjected to infrastructural issues. While inclusion errors are at least in principle targeted by the rationale of biometrics, exclusions keep happening, and put into serious predicament a social welfare system that should cover exactly the most vulnerable groups.

COVID-19: A Reshuffling of Priorities

In the midst of the ongoing crisis, many studies are being conducted on the effects of COVID-19 on health infrastructures and, crucially here, economic vulnerabilities in the Global South. Studies of factory workers, gig-workers and low-income households all point in the same direction: the economic impact brought by national lockdowns is disproportionally affecting the poor and vulnerable, large proportions of whom are recipients of social welfare systems. Where such systems have limited reach or are not available, measures of immediate assistance are invoked, such as the provision of universal basic income or emergency social safety nets. In the Indian PDS, the promise of doubling foodgrain rationsalong with providing extra commodities increases the scheme’s cruciality, in a situation in which new vulnerabilities–such as that of migrant workers exposed to distress and food insecurity–have emerged in the wake of lockdown.

In these times of heightened crisis, severely affecting the users of anti-poverty schemes, the exclusion errors induced by mandatory biometric access are a risk that social protection schemes cannot afford to take. While the incorporation of biometrics is purposefully designed to improve targeting, the crisis poses us in front of the priority of reaching out to the most affected, adapting systems in such a way that biometric recognition–or its digital equivalents–are suspended at the very least. While the problem of touchscreen-induced disease transmission is in itself a valid reason for doing so, the inclusion-exclusion trade-off illustrated here equally poses a problem that needs consideration. As systems are adapted to coping with the COVID-19 crisis, the need for assisting the affected needs to prevail on the stringent adoption of biometric credentials.

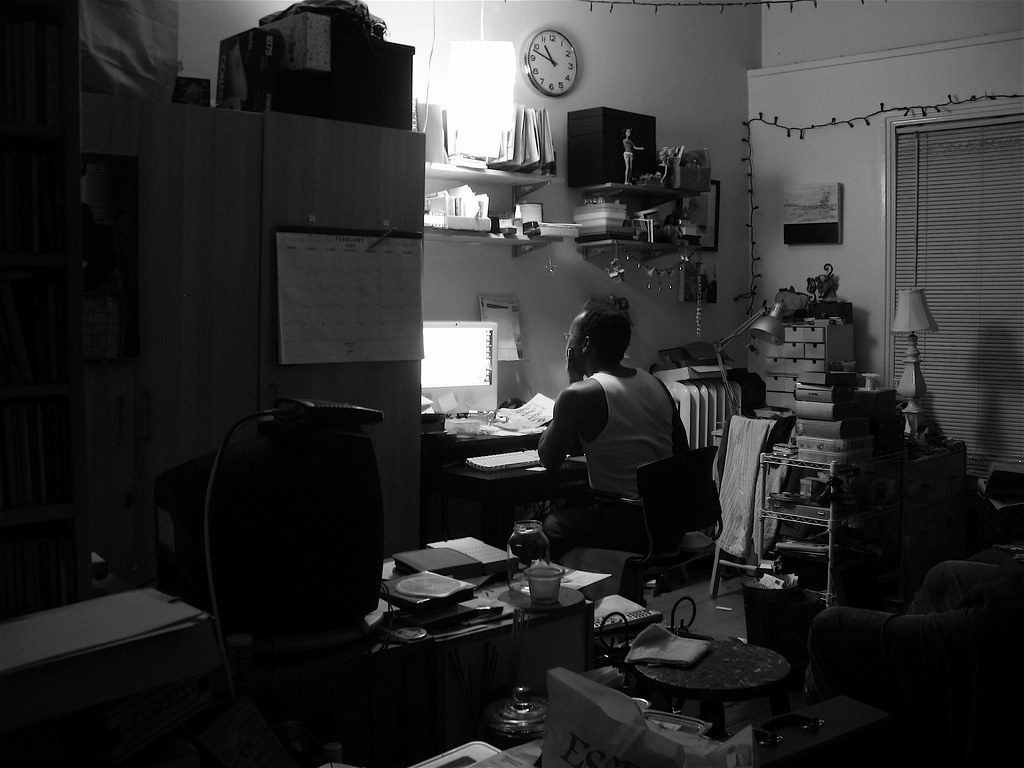

Photo: A ration shop in Tumkur, Karnataka, April 2018