Por Marta Espuny Contreras*

Las respuestas colectivas como redes de apoyo mutuo y solidaridad y, en concreto, las cajas de resistencia (despensas solidarias, fondos de emergencia, etc.) se han multiplicado a raíz de la pandemia del COVID-19. Se trata de un tipo de activismo digital, unas prácticas de resistencia centradas en el apoyo colectivo y la solidaridad comunal que se han venido desarrollando especialmente en redes sociales.

En este texto se plantea una reflexión crítica sobre los conflictos y contradicciones que derivan del uso de redes centralizadas -como Instagram o Facebook- para la creación y coordinación de redes autónomas, basándonos en las siguientes preguntas: ¿qué posibilidades autónomas de resistencia se activan dentro de estas plataformas?, ¿qué consiguen estos movimientos al hacer uso de las redes sociales? Hablaremos de la fragmentación que sufre el activismo en redes sociales, y cómo las redes estudiadas superan esa centralización e individualización mediante la localidad, es decir, anteponiendo el sentimiento de pertenencia y responsabilidad mutua que diseña un acuerpamiento y una lucha desde la identidad. Esta localidad, adelantamos, necesita ser reconfigurada pues ya no se lee con relación a un espacio compartido sino a una identidad común.

Vulnerabilidad social, exclusión y redes comunitarias: Instagram como objeto político

La actual pandemia ha puesto en evidencia las numerosas deficiencias de nuestras no tan bien consolidadas democracias europeas. Las redes de apoyo mutuo surgían como única alternativa válida de supervivencia para los sectores de la sociedad denominados por Sousa Santos como no-existentes; personas y poblaciones que, por su procedencia, falta de regulación laboral, identidad de género, profesión -o todo lo anterior-, permanecen invisibles en los márgenes y no cuentan con el reconocimiento necesario para beneficiarse de las medidas gubernamentales. Una precariedad que aumenta con la imposibilidad de trabajar durante el periodo de confinamiento (o, en algunos casos como los temporeros de Lleida, incluso trabajando).

Es en este contexto el que surge la necesidad para estos colectivos de repensar sus mecanismos de supervivencia, de crear redes de solidaridad, cuidados colectivos y apoyo mutuo, frente a los paradigmas individualistas occidentales. Estas acciones se presentan como la única alternativa simbólica y material de los colectivos de no-existentes. La construcción autónoma de estos espacios-red es una forma disidente de establecer relaciones de apoyo en las que sus integrantes pasan de ser víctimas -de un sistema, unas jerarquías, una pandemia, de la imposibilidad de adquirir lo mínimo para vivir- a agentes activos, apropiándose del centro de acción y decisión. Cuando estas redes de colaboración se expanden hacia las plataformas digitales, encontramos muchos perfiles que se caracterizan por su gran conciencia identitaria en relación con las exclusiones y procesos de discriminación nombrados con anterioridad.

Desde la Teoría de Medios (STS) las plataformas se entienden como espacios de mediación, que responden a intereses empresariales y económicos -capitalización de datos, captación de la atención-, por lo que no son elementos neutros, sino que están al servicio del sistema. Es en esta mediación y la estandarización -influencia del diseño de la plataforma- donde reside la clave a la hora de entender las posibilidades de inter(acción) que ofrecen estas plataformas a los diferentes actores que la transitan.

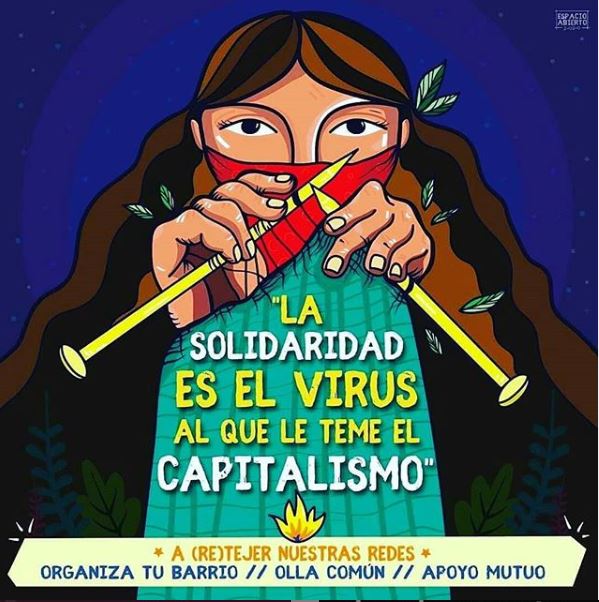

Los discursos políticos y activistas se expanden hacia lo digital, donde se fragmentan y estandarizan por la mediación de estas plataformas, quedando reducidos a imágenes, slogans o pequeños textos a pie de foto. En un contexto dominado por la economía de la atención, se publican consignas agresivas y provocadoras, con una aparentemente alta carga política, buscando generar un mayor impacto y destacar entre la sobresaturación de información.

Sin embargo, estos mensajes no pueden presentarse de manera articulada, puesto que las redes sociales no ofrecen la posibilidad de extender los discursos, no dan lugar a que se dibuje un hilo conductor de las reivindicaciones.

Transformando sus narrativas al formato Instagram, las luchas políticas quedan condicionadas por la búsqueda del impacto y la atención. De esta lógica surge la mediada visibilidad, que produce que ciertos perfiles cuenten con mayor visibilidad, mientras que otros perfiles queden aislados en sus comunidades de afines. Esta invisibilización de determinados perfiles hace de Instagram una herramienta de censura y no de amplificación. Las redes y plataformas de comunicación tecnológicas suponen, en este sentido, una amenaza para la emancipación de movimientos autónomos. Entonces, retomando nuestra pregunta inicial, cabe cuestionarse ¿qué posibilidades autónomas de resistencia se activan dentro de estas plataformas?

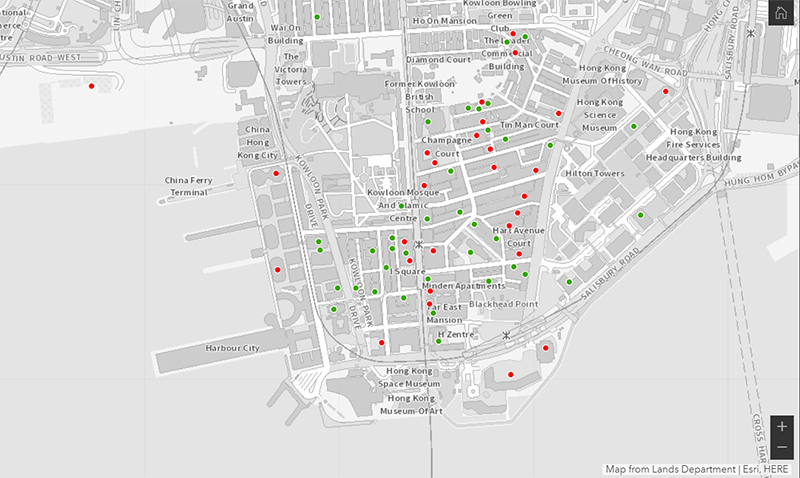

Para indagar en las posibilidades autónomas que se movilizan dentro de estas plataformas, hemos analizado tres hashtags: #CajaResistencia, #TejidoComunitario y #SolidaridadComunitaria, desde los cuales se ha realizado un muestreo en cadena hasta identificar un total de 40 perfiles (principio de saturación discursiva). Perfiles gestionados por personas o colectivos migrantes o que practiquen un trabajo no regulado (venta ambulante, trabajo sexual, recogida de fruta, etc.), establecidos en el Estado Español, y que publicaron llamados a participar en cajas de resistencia durante el confinamiento por COVID-19 en España.

Activismo y localidad

Los efectos de la estructura, los límites e intereses de las plataformas recaen sobre sus interacciones. Es desde este punto que estos colectivos tienen la necesidad de utilizar las affordances de estos medios para realizar apropiaciones concretas que les permitan la acción. Con relación a las cajas de resistencia hemos percibido cómo estos colectivos, consciente o inconscientemente, ponen el foco en la localidad y en los cuidados. Es decir, superan la fragmentación, centralización e individualización de las redes gracias a que anteponen la localidad, a que se priorizan los lazos comunitarios que hacen de nexo entre diferentes colectividades.

Desde esta perspectiva, resulta necesaria una reconfiguración del término localidad, que pasa de lo físico a lo simbólico, de lo material a lo identitario. Ya no implica necesariamente que se comparta un mismo espacio, sino más bien que se lea a la otra persona como parte de tu grupo. Entendiendo el grupo como las personas tienen un mismo origen, que combaten dentro de las mismas luchas (como antirracismo, disidencia de género, anticolonialismo, transfeminismo, etc.), o que comparten objetivos o prioridades comunes, líneas o espacios de debate, proyectos, etc.

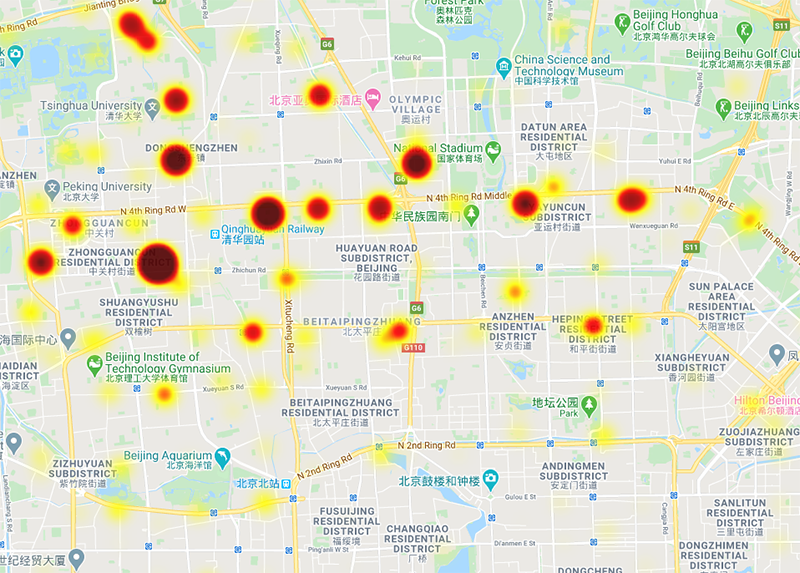

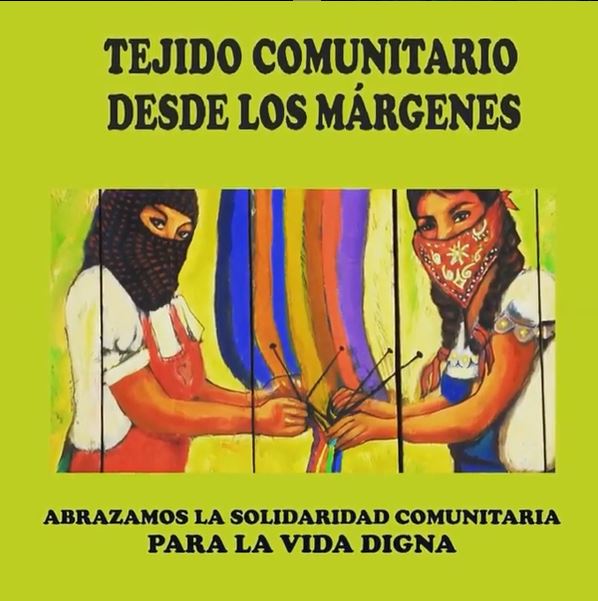

Al publicar (e interesarse por) mensajes y proclamas sobre la misma lucha, perfiles que podrían no llegarse a conectar nunca, debido a las limitaciones espaciotemporales, empiezan a interrelacionarse dentro de los espacios digitales. En la siguiente imagen vemos un ejemplo de cómo la conciencia identitaria resulta una base, un nexo de localidad que, en el caso de la ayuda mutua, tienen claras referencias a las comunidades indígenas que tanta experiencia tienen en este tipo de redes. Reclamos como “tejido comunitario desde los márgenes” o “abrazamos la solidaridad comunitaria para la vida digna” representan esa búsqueda de solidaridad, de acuerpamiento entre iguales. Se subraya la solidaridad como respuesta de contingencia para hacer frente al capitalismo.

Por otro lado, es fundamental la capacidad de las redes sociales para escalar esa localidad, para trascender las barreras locales y nacionales y construir redes de solidaridad globales. Esto se da gracias a la atemporalidad presente en las redes sociales, entendida como el fenómeno que facilita la comunicación simultánea desde diferentes zonas geográficas (lo que Castells denominó timeless time), que hace de las redes un espacio compartido más allá de las limitaciones y barreras de la comunicación presencial. Partiendo de lo local (punto de partida necesario para la construcción de redes disidentes), estos espacios permiten la creación de redes translocales y transnacionales que son, en definitiva, tecnologías preservación colectiva de la vida.

Subrayar el carácter revolucionario de la generación de redes de apoyo mutuo. La mera construcción y subsistencia de estas cajas de resistencia en redes sociales supone una revolución en sí misma, puesto que demuestra que es posible la existencia desde, por y para los márgenes. En esta época lo vemos como una medida urgente, de contingencia frente a la falta de recursos. Sin embargo, la autogestión de tejidos comunitarios podría extrapolarse como solución frente a la centralización capitalista. Con respecto a proyectos de emancipación y autonomía, tenemos mucho que aprender de los paradigmas y estructuras creadas desde las diásporas, de sus tecnologías ancestrales de supervivencia. Se trata de un trabajo de descolonización para sustituir los paradigmas individualistas por proyectos locales y autónomos que busquen una emancipación colectiva, que rompan con la relación de codependencia generada a través de los años con los estados y el capital.

* Marta Espuny es una persona en deconstrucción, cuyos intereses se centran en el análisis social y político de/en espacios digitales -digital humanist/researcher-. Trabaja desde una mirada crítica en la intersección entre ciencia y tecnología, platform politics y cambio social. Twitter: @martaespuny Linkedin: MARTA ESPUNY