Why study Big Data from the South? This was the question we – the founder of the Big Data from the South Initiative and the author of this blog post – asked by pulling together a three-session workshop and panel series on “Big Data from the South” at the 2018 Latin American Studies Association Conference (LASA), that took place in May of this year in Barcelona, Spain. The timing of the series was auspicious. That very month, the European Union’s new General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) – a law introducing new reforms that intended to strengthen EU citizens’ control over personal data, privacy rights, and ensure organizations that collect data do so only with a user’s consent, and while ensuring its protection from misuse and exploitation – had come into enforcement. And only months earlier, the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal had come to public light – in a case that put the world’s biggest social network at the center of an international scandal involving the manipulation of user data and voter profiles for global misinformation campaigns. The case was all the more significant for demonstrating not only the possibility of hacking electoral processes in the 2016 US presidential election or the UK Brexit referendum campaign – but for making evident the pre-existing and potentially continuing precarity of global electoral processes well beyond. That very month, while Silicon Valley corporate heads in the US pronounced to publics around the world that they should continue to be trusted – as data’s and Western liberal economies’ foremost technical experts – with the design and management of data ecologies, across the Atlantic, EU political representatives made parallel arguments for renewed public trust (voting scandals aside) around data policy, leveraging their authority as key spokespersons of the Western world’s legal and political expertise.

The varied crises currently facing Western data institutions – private and public alike – gave an immediate urgency to deepen our understanding and analyses of other forms of data practice and processing beyond the given centers of “data” expertise – technical, legal, or otherwise. But the work of this volume demonstrates the breadth of scholarship long underway from across varied disciplines and research communities (bridging from Latin American and global area studies, to communications and new media studies, anthropology, sociology, science and technology studies, and emerging fields like critical data studies) to address such glaring imbalances – to ask what limited forms of citizen and user are indeed “spoken for” under the interests of Western innovation and political centers –and to ask how it is that such particular centers of knowledge production and research are still enabled to speak for (and in place of) the “global rest”– particularly when issues of technology, the digital, and now indeed, data are involved.

In bringing the LASA session series together, we thus noted how critical scholarship had already begun to undertake analyses of the politics surrounding big data – drawing attention to how datafication regimes bring about new and opaque techniques of population management, control, and discrimination – but how such accounts still largely stemmed from scholars based in institutions in the global north. Our aim was thus to build and expand upon such scholarship by engaging dialogues with new and existing work critical of the dominance of Western approaches to datafication, and that aimed towards recognition of the diversity of voices emerging from the Global South. Stressing opportunities for co-learning across dialogues, we tabled a range of questions that included:

- How does the availability of data bring novel opportunities for research and collaboration across the Global South?

- How do activists take advantage of big data for social justice advocacy?

- What initiatives and actors ask for the release of data?

- What negative consequences of datafication are activists and organizations facing in the Global South?

- What practices of resistance emerge?

- What frames of reference, imaginaries, and culture do people mobilize in relation to big data and massive data collection?

- Which conceptual and methodological frameworks are best suited to capture the complexity and the peculiarities of data activism in the Global South?

- And which alternative understandings and epistemologies could help us to better address the contested terrain of data power and activism in the Global South, and Latin America in particular?

The shift involved not only a broadening of geographical and political lenses, but also entailed a broadening of frameworks to encompass – alongside the critical work of analyzing datafication regimes under development by state and corporate actors – new frameworks that could take new and existing practices around data activism seriously. Parallel with growing calls for broadening debates in information, technology and new media studies with “decolonial computing” frameworks (Amrute and Murillo 2018, Chan, 2018, Philip and Sengupta, 2018), such a broadened lens draws from work in Latin American and post-colonial studies around the “decolonization of knowledge” as a means to underscore the significance of the diverse ways through which citizens and researchers in the Global South engage in bottom-up data practices for social change as well as speak for the resistances to uses of big data that increase oppression, inequality, or social harm. Indeed, the prominent collective of global scholars who wrote of decolonial thinking and the “decolonial option” in 2007 did so urging a broader recognition of the diverse contexts and agents of knowledge production who long represented “a colonial subaltern epistemology.” They wrote to draw attention to the long and diverse histories of decolonial interventions that emerged to confront the “variegated faces of the colonial wound inflicted [over] five hundred years of… modernity as a weapon of imperial/colonial global expansion.” (Mignolo, 2007, Mignolo and Escobar, 2010)

Writing as researchers bridging conversations and debates across four continents, they renewed critiques of how the colonial underpinnings of global knowledge production continued to reassert Western frames of thought as universal scientific truths. And they underscored how this “historically worked to subordinate and negate ‘other’ frames [and] ‘other’ knowledge,… reproduc[ing] the meta-narratives of the West while discounting or overlooking the critical thinking produced by indigenous, Afro, and mestizos whose thinking… depart not from modernity alone but also from the long horizon of coloniality” (Walsh, 2007: 224). They thus stressed the vitality of “other” forms of knowledge production occurring “beyond the academy” (Mignolo and Escobar 2010:18), and highlighted the de-colonial options enacted by indigenous and other social movement actors as vital to future decolonial projects. Pressing on “the importance of thinking within” and alongside the perspective of these movements (Mignolo and Escobar 2010:19), they urged scholars not only to reimagine their roles as academic documentarians of movements (actors, that is, still dedicated to a reproduction of dominant forms of modern epistemologies) , but to decenter their own forms of knowledge practice by beginning to “think with [movements] theoretically and politically.” As such, decolonialists posed the significance of how cultivating a politics of decentralization – and a de-centering of the self as expert and knowledge practitioner – might offer an affront to modernity’s domination of other epistemologies – and might open up possibilities for a more radical politics of inclusion and intentionality of dialogues across lines of difference.

And indeed, the encounter in Barcelona last May drew forth vital and vibrant responses from a diverse range of scholars who together represented more than 20 different research institutions (public and private) across over more than a dozen national contexts, and four different continents. Building upon the prompt the editors of this volume following the first conference on Big Data from the South in Cartegena, Colombia to imagine what varied southern theories – in vital, vibrant, plurality — around big data would entail (Milan and Trere, 2017), the participants of our second workshop mapped collaboratively a terrain marked by a complex of readily identifiable contemporary challenges and possibilities alike. These included varied forms of new datafication practices undertaken by the state – but conducted in fundamental partnership with corporate data industries – that were read as explicitly deleterious to civic forms of critical intervention. These encompassed projects that participants marked as material and techno-cultural articulations of “Nation branding,” “Surveillance” in urban and online spaces alike, growing “Smart City Initiatives” that saw to the “Automation of State Functions within Urban Infrastructures,” growing CCTV-like “Centers of Control with Cameras,” and indeed, “Bureaucracy.”

Other participants marked emerging data-driven projects launched under state and private sector partnerships that – less than outright excluding or marginalizing civic participation – instead included narrowly-defined forms of citizen inclusion, that were typically based on recognizable forms of “innovation” practice. This included noticeably growing trends in “Open Government” and “Open Data” initiatives “and “Open Innovation Centers” as a means to transform citizens’ perceptions of and relations to the state.

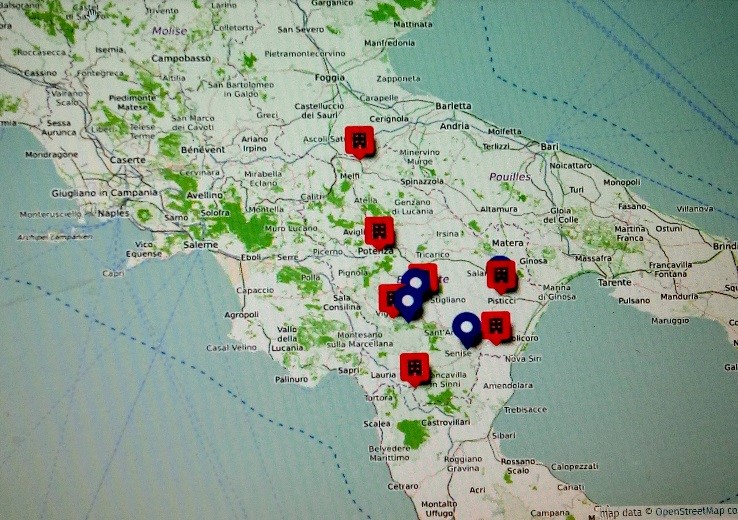

Mapping more promising vectors, participants noted new growth in the use of “media archives” in film, video, literature, or music and civic data collections as resources newly utilized for new citizen-driven projects around “Data Literacy,” “Memory Mappings and Weavings from Neighborhoods” (including those especially marked by conflict and violence, such as those in urban Colombia), “Communal and Neighborhood Open Street Maps”, and “Feminist Mappings of Femicides” and sex-based hate crimes. Participants also marked the development of new practices or use of existing data sets (acquired from either government, public, or corporate data sources) – as practices that drew from existing data resources or infrastructures, and reoriented or hacked them to create fundamentally new technocultural and material resources. This included the “Reappropriation of Stolen Archives” and cultural artifacts taken (whether under colonial powers or in the name of national patrimony) from traditional and indigenous communities, the “Use of Drones to Map Marches” and document potential state abuses, the “Use of Analog Phone Communication between Taxi Drivers” as a means to circumvent smart city programs in Mexico City, and even the outright “Rejection and Refusal” of dominant technology products and solutions, until alternative civic uses might be defined.

Working together over the course of the afternoon-long session, the participants brought to life a number of principles underscored in the earliest iteration of Big Data from the South that alternatives theories and approaches to big data would entail. This included a considerations of the heterogeneity of data practices – coming from state, corporate and also civic actors – who could facilitate or resist “datafication” processes, to center decolonial thinking that would attend to alternative practices, imaginaries, and epistemologies in relation to data; to consider the work of infrastructure within diverse contexts in the Global South; and to be open to the dialogue the varied vectorizations it might have between actors representing diverse and complex realities between “northern” and “southern” worlds.

In conversation, and in consideration of the recent globally-scaled data scandals of 2018 that had brought the legitimacy of national elections and the authority of dominant Western data institutions – private and public alike – into question – the roomful of participants began to collectively map a series of other concerns and problematics that built upon earlier mappings. This included how data archives and practices had been influenced by community-defined communication infrastructures. It included too how other objects that defined people’s day to day contact with data resources might especially be mindful of how everything from seeds to digitally tagged farm animals (and objects beyond cell phones and urban smart city infrastructures) might be recognized as implicating datafication in more-than-human worlds. How might such considerations and practices developing within community contexts – and that draw attention to the rights, responsibilities and obligations around “community data” or “comuni-datos” – how might these emerge as a collective argument and resource to defend as an alternative to Western framework’s privileging of individual privacy rights (or data as personal property). How might recognizing the innovation within such work deepen a decolonial data project by decentering recognition of conventional data experts – as industry employed or IT-trained data scientist and engineer – to more everyday forms of data expert and practice centered around citizen and civic actors? And finally, could taking seriously the work of such processes as Data Dialogues help to forge new convergences, interfaces, or forms of technosocialities that could further deepen the ethical debates and intersectional, inter-allied work needed to energize the development of alternative data practices in the face of the evident global crises of dominant data institutions today confront?

It is worth noting that such a project and core of concerns within a Data from the South initiative finds ready resonances within existing debates in critical data studies, and the growing scholarship around algorithm studies, software and platform studies, and post-colonial computing. And while most of this scholarship has indeed emerged from institutions in the Global North, varied concerns scholars within such circles have signaled as key areas for future development, indeed point towards potentials for convergences. This includes a reinforced rejection of data fundamentalism (Crawford and boyd) and technological determinism infused within many analysis of algorithms in application, and a fundamental recentering of the human within data-fied worlds and data industries – that resists the urge to read “algorithms as fetishized objects… and firmly resist[s] putting the technology in the explanatory driver’s seat… A sociological analysis must not conceive of algorithms as abstract, technical achievements, but must unpack the warm human and institutional choices lie behind these cold mechanisms. (Gillespie 2013, Crawford 2016) It also involves treating data infrastructures and the underlying algorithms that give political life them intentionally as both ambiguous but approachable – to develop methodologies that “not only explore new empirical [and everyday] settings,” for data politics, including airport security, credit scoring, academic writing, and social media – “ but also find creative ways to make the figure of the algorithm productive for analysis… [and] show that mythologies like the algorithmic drama do not have to be reductive but can be rich and complex ‘stories that help people deal with contradictions in social life that can never fully be resolved’’ (Mosco 2005, 28; see also Lévi-Strauss 1955). Finally, in parallel with approaches for a post-colonial computing that STS and critical informatic scholars have called for have called for (Irani, Phillips and Dourish 2010) in developing decolonial computing frameworks that aim for growing “tactics… that expand the transdisciplinary scope of what one needs to know,” developing approaches around and with Data from the South might further aim to develop new interfaces with allied scholars – from across varied disciplines and regions – required to “think within” between and among in the diverse perspective of wide-ranging and widely-situated movements both inside and outside traditional research spaces. Writing now in the Fall of 2018, as renewed calls for alternative and urgently needed forms of global political imaginaries that no longer take for granted a presumed stability and centrality of Western liberalism and modernity are being called upon, such forms of open-ended relating and experimentation indeed yield valuable lessons.

References

Amrute S. and L. R. Murillo. (2018). “Computing in/from the South.” Catalyst, 4(2).

Andrejevic, M. (2012). Exploitation in the data-mine. In C. Fuchs, K. Boersma, A. Albrechtslund, & M. Sandoval (Eds.), Internet and Surveillance: The Challenges of Web 2.0 and Social Media (pp. 71–88). New York: Routledge.

Arora, P. (2016). Bottom of the Data Pyramid: Big Data and the Global South. International Journal of Communication, 10, 19.

Boyd, d., & Crawford, K. (2012). Critical questions for big data: Provocations for a cultural, technological, and scholarly phenomenon. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 662–679.

Chan, A. (2014). Networking Peripheries: Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chan, A. 2018. “Decolonial Computing and Networking Beyond Digital Universalism.” Catalyst, 4(2).

Crawford, K. 2016. Can an Algorithm be Agonistic? Ten Scenes from Life in Calculated Publics, Science, Technology & Human Values, 41(1), 77-92.

Crawford, K., Miltner, K., and M. Gray. (2014). “Critiquing Big Data: Politics, Ethics, Epistemology,” International Journal of Communication 8, 1663–1672.

Dourish, P. (2016). “Algorithms and their others: Algorithmic culture in context.” Big Data & Society, July–December 2016: 1–11.

Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police and Punish the Poor. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In T. Gillespie, P. Boczkowski, & K. Foot (Eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality, and society (pp. 167–194). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Introduction: Coloniality of power and de-colonial thinking. Cultural Studies, 21, (2 -3 March/May), 155 -167.

Mignolo, W. D. & E. A. Escobar (Eds.). (2010). Globalization and the decolonial. London, GB: Routledge Press.

Milan, S., & Trere, E. (2017). Big Data from the South: The Beginning of a Conversation We Must Have.

Mosco, V. 2005. The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power, and Cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Noble, S. (2018). Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press.

O’Neil, Cathy. (2016). Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy. London: Allen Lane.

Philip, K., Irani, L. & Dourish, P. (2010). Postcolonial computing: A tactical survey. Science, Technology, & Human Values. 37(1), 3–29.

Philip, K. and A. Sengupta. 2018. “Afterword: Computing in/from the South.” Catalyst, 4(2).

Schäfer, M. & K. van Es, eds. (2017). The Datafied Society: Studying Culture through Data. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Walsh, C. (2007). Shifting the geopolitics of critical knowledge: Decolonial thought and cultural studies “others” in the Andes. Cultural Studies 21, (2-3 March/May), 224 -239.

Ziewitz, M. (2015). “Governing algorithms: Myth, mess, and methods.” Science, Technology & Human Values 41(4): 3– 16.

About the author

Anita Say Chan is an Associate Research Professor of Communications in the Department of Media and Cinema Studies at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Her research and teaching interests include globalization and digital cultures, innovation networks and the “periphery”, science and technology studies in Latin America, and hybrid pedagogies in building digital literacies. She received her PhD in 2008 from the MIT Doctoral Program in History; Anthropology; and Science, Technology, and Society. Her first book the competing imaginaries of global connection and information technologies in network-age Peru, Networking Peripheries: Technological Futures and the Myth of Digital Universalism was released by MIT Press in 2014. Her research has been awarded support from the Center for the Study of Law & Culture at Columbia University’s School of Law and the National Science Foundation, and she has held postdoctoral fellowships at The CUNY Graduate Center’s Committee on Globalization & Social Change, and at Stanford University’s Introduction to Humanities Program. She is faculty affiliate at the Institute for Computing in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (I-CHASS), the Illinois Informatics Institute, the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory, and the Collaborative for Cultural Heritage Management and Policy (CHAMP). She was a 2015-16 Faculty Fellow with the Illinois Program for Research in the Humanities. She will be 2017-18 Faculty Fellow with the National Center for Supercomputing Applications, and a 2017-19 Faculty Fellow with the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory.