Author: Miren Gutierrez

This is a response the call for a critical community studies ‘Tech, data and social change: A plea for cross-disciplinary engagement, historical memory, and … Critical Community Studies‘ by Kersti Wissenbach and the first contribution to the debate ‘Can We Plan Slow – But Steady – Growth for Critical Studies?’ by Charlotte Ryan.

Commenting on the thought-provoking blogs by Charlotte Ryan and Kersti Wissenbach, I feel in good company. Both of them speak of the need in research to address inequalities embedded in technology and to focus on the critical role that communities play in remedying dominant techno-centric discourses and practices, and of the idea of new critical community studies. That is, the need to place people and communities at the centre of our activity as researchers and practitioners, asking questions about the communities instead of about the technologies, demanding a stronger collaboration between the two, and the challenges that this approach generates.

Their blogs incite different but related ideas.

First, different power imbalances can be found in scholarship. Wissenbach suggests that dominant discourses in academia, as well as in practice and donor agendas, are driving the technology hype. But as Ryan proposes, academia is not a homogeneous terrain.

Always speaking from the point of view of critical data studies, the current predominant techno-centrism seems to be diverting research funding towards applied sciences, engineering and tools (what Wissenbach calls “the state of technology” and Ryan refers to as a “profit-making industry”). Talking about Canada, Srigley describes how, for a while, even the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada “fell into line by focusing its funding on business-related degrees. All the while monies for teaching and research in the humanities, social sciences, and sciences with no obvious connection to industry, which is to say, most of it, began to dry up”(Srigley 2018). Srigley seems to summarise what is happening everywhere. “Sponsored research” and institutions requiring that research can be linked to business and industry partners appear as the current mantra.

Other social scholars around me are coming up with similar stories: social sciences focusing critically on data are getting a fraction of the research funding opportunities vis-à-vis computational data-enabled science and engineering within the fields of business and industry, environment and climate, materials design, robotics, mechanical and aerospace engineering, and biology and biomedicine. Meanwhile, critical studies on data justice, governance and how ordinary people, communities and non-governmental organisations experience and use data are left for another day.

Thus, the current infatuation with technology appears not to be evenly distributed across donors and academia.

Second, I could not agree more with Wissenbach and Ryan when they say that we should take communities as entry points in the study of technology for social change. Wissenbach further argues against the objectification of “communities”, calling for actual needs-driven engaged research and more aligned with practice.

Then again, here lies another imbalance. Even if scholars work alongside with practitioners to bolster new critical community studies, these actors are not in the same positions. We, social scholars, are gatekeepers of what is known in academia, we are often more skilful in accessing funds, we dominate the lingo. Inclusion therefore lies at the heart of this argument and remains challenging.

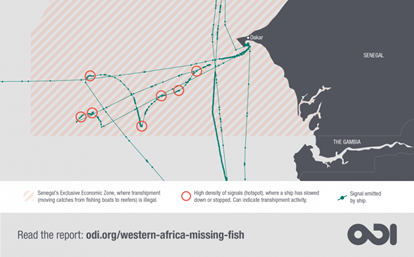

If funds for critical data studies are not abundant, resources to put in place data projects with social goals and more practice engaged research are even scarcer. That is, communities facing inequalities may find themselves competing for resources not only within their circles (as Ryan suggests). Speaking too as a data activist involved in projects that look at illegal fishing’s social impacts on coastal communities of developing countries (and trying hard to fund-raise for them), I think that we must make sure that more possible for data activism research does not mean less funding for data activist endeavours. I know they are not the same funds, but there are ways in which research could foster practice, and one of them is precisely putting communities at the centre.

Third, another divide lies underneath the academy’s resistance to engaged scholarship. While so-called “hard sciences” have no problems with “engaging”, some scholars in “soft-sciences” seem to recoil from it. Even if few people still support Chris Anderson’s “end of theory” musings (Anderson 2008), some techno-utopians pretend a state of asepsis exists, or at least it is possible now, in the age of big data. But they could not be more misleading. What can be more “engaged scholarship” than “sponsored research”? I mean, research driven and financed by companies is necessarily “engaged” with the private sector and its interests, but rarely acknowledges its own biases. Meanwhile, five decades after Robert Lynd asked “Knowledge for what?” (Lynd 1967), this question still looms over social sciences. Some social scientists shy away from causes and communities just in case they start marching into the realm of advocacy and any pretentions of “objectivity” disappear. While we know computational data-enabled science and engineering cannot be “objective”, why not accept and embrace engaged scholarship in social sciences, as long as we are transparent about our prejudices and systematically critical about our assumptions?

Fourth, data activism scholars have to be smarter in communicating findings and influencing discourses. Our lack of influence is not all attributable to market trends and donors’ obsessions; it is also our making. Currently, the stories of data success and progress come mostly from the private sector. And even when prevailing techno-enthusiastic views are contested, prominent criticism comes from the same quarters. An example is Bernard Marr’s article “Here’s why Data Is Not the New Oil”. Marr does not mention the obvious, that data are not natural resources, spontaneous and inevitable, but cultural ones, “made” in processes that are also “made” (Boellstorff 2013). In his article, Marr refers only to certain characteristics that make data different from oil. For example, while fossil fuels are finite, data are “infinitely durable and reusable”, etc. Is that all that donors, and publics, need to know about data? Although this debate has grown over the last years, is it reaching donors’ ears? Not long ago, during the Datamovida conference in Madrid in 2016 organised by Vizzuality, a fellow speaker –Aditya Agrawal from the Open Data Institute and Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data— opened his presentation saying precisely that data were “the new oil”. If key data people in the UN system have not caught up with the main ideas emerging from critical data studies, we are in trouble and it is partly our making.

This last argument is closely related to the other ideas in this blog. The more we can influence policy, public opinion, decision-makers and processes, the more resources data activism scholars can gather to work alongside with practitioners in exploring how people and organisations appropriate data and their processes, create new data relations and reverse dominant discourses. We cannot be content with publishing a few blogs, getting our articles in indexed journals and meeting once in a while in congresses that seldom resonate beyond our privilege bubbles. Both Wissenbach and Ryan argue for stronger collaborations and direct community engagement; but this is not the rule in social sciences.

Making an effort to reach broader publics could be a way to break the domination that, as Ryan says, brands, market niches and revenue streams seem to exert on academic institutions. Academia is a bubble but not entirely hermetic. And even if critical community studies will not ever be a “cash cow”, they could be influential. There are other critical voices in the field of journalism, for example, which have denounced a sort of obsession with technology (Kaplan 2013; Rosen 2014). Maybe critical community studies should embrace not only involved communities and scholars but also other critical voices from journalism, donors and other fields. The collective “we” that Ryan talks about could be even more inclusive. And to do that, we have to expand beyond the usual academic circles, which is exactly what Wissenbach and Ryan contend.

I do not know how critical community studies could look like; I hope this is the start of a conversation. In Madrid, in April, donors, platform developers, data activists and journalists met at the “Big Data for the Social Good” conference, organised by my programme at the University of Deusto focussing on what works and what does not in critical data projects. The more we expand this type of debates the more influence we could gain.

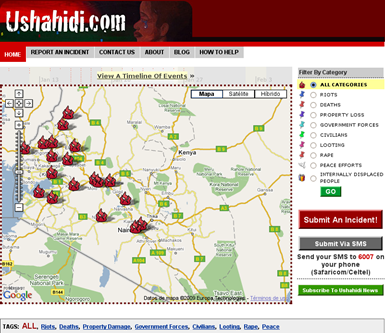

Finally, the message emerging from critical data studies cannot be only about dataveillance (van Dijck 2014) and ways of data resistance. However imperfect and biased, the data infrastructure is enabling ordinary people and organised society to produce diagnoses and solutions to their problems (Gutiérrez 2018). Engaged research means we need to look at what communities do with data and how the experience the data infrastructure, not only at how communities contest dataveillance, which I have the feeling has dominated critical data studies so far. Yes, we have to acknowledge that often these technologies are shaped by external actors with vested interests before communities use them and that they embed power imbalances. But if we want to capture people’s and donor’s imagination, the stories of data success and progress within organised and non-organised society should be told by social scholarship as well. Paraphrasing Ryan, we may lose but live to fight another day.

Cited work

Anderson, Chris. 2008. ‘The End of Theory: The Data Deluge Makes the Scientific Method Obsolete’. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2008/06/pb-theory/.

Boellstorff, Tom. 2013. ‘Making Big Data, in Theory’. First Monday 18 (10). http://firstmonday.org/article/view/4869/3750.

Dijck, Jose van. 2014. ‘Datafication, Dataism and Dataveillance: Big Data between Scientific Paradigm and Ideology’. Surveillance & Society 12 (2): 197–208.

Gutierrez, Miren. 2018. Data Activism and Social Change. Pivot. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kaplan, David E. 2013. ‘Why Open Data Isn´t Enough’. Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN). 4 February 2013. http://gijn.org/2013/04/02/why-open-data-isnt-enough/.

Lynd, Robert Staughton. 1967. Knowledge for What: The Place of Social Science in American Culture. Princeton: Princeton University Press. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/aa.1940.42.1.02a00250/pdf.

Rosen, Larry. 2014. ‘Our Obsessive Relationship With Technology’. Huffington Post, 2014. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-larry-rosen/our-obsession-relationshi_b_6005726.html?guccounter=1.

Srigley, Ron. 2018. ‘Whose University Is It Anyway?’, 2018. https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/whose-university-is-it-anyway/#_ednref37.