This article reflects on the role of “WhatsAppers”, defined as social activists appropriating WhatsApp as a primary platform to organize and communicate, in relation with the rise of Bolsonarism in Brazil. Affordances of WhatsApp usage by social actors are explored in the light of responses to Bolsonarism, along with their implications in the current time of crisis.

By Sérgio Barbosa

The research illustrated explores the affordances of WhatsApp and its appropriation by the WhatsAppers in Brazil, here defined as social activists appropriating WhatsApp as a primary platform to organize and communicate. I explore the importance of the Global South context in shaping such affordances, focusing on local epistemologies which bypass the structure of mainstream Brazilian media. As illustrated elsewhere, the empirical analysis combined different qualitative methods, yielding insights into the communication and action repertoire of the group studied, not without considering reflections on research ethics and their implications in the context studied.

WhatsAppers: Towards a new research agenda

This research stems from an analysis of the social interactions of UnidosContraOGolpe (UCG), a leftist group in Brazil, which was a WhatsApp “private group” emerged in 2016 to oppose the controversial impeachment of the then-president Dilma Rousseff. The case study resulted into the first empirical MA dissertation in Latin America to explore digital activism on WhatsApp private chats as an emerging field of political action. To do so, a ‘meso-micro’ analysis was used – on the meso level, to identify the modus operandi of group interactions and, on the micro level, to capture individual motivations, tensions, and expectations. At the core of the investigation, the researcher’s identity was disclosed, following social actors through their chat environment and adopting an ‘engaged’ approach, whereby the research is designed with the goal of empowering social actors. In practical terms, this inspired a triangulation of qualitative methods, including digital ethnography (to identify and analyze the practice of social actors inside the chat domain, through a long “zoom” perspective on social interactions in the private chat group), content analysis of selected posts (to understand how the group emerged organically and self-organized in a contingent manner) and fifteen in-depth semi-structured interviews (to elicit values and motivations from the perspective of individual active participants).

This dissertation argues that WhatsAppers are characterized by their ability to appropriate the chat group as a means to participate in political life. Engagement with political activism becomes an intimate and familiar affair, mediated by a personal and omnipresent device, that enables a unique approach to mobilization. In general lines, everyone could be a WhatsApper, including those not previously politically active. A WhatsApper could be someone who already is entwined in other social media networks of politics and mobilization or not; they can be someone from a poor, middle or rich class background. In other words, WhatsAppers interact digitally with others, combining online and offline political actions. Through the lens of digital sociology, the case studied reveals that WhatsApp stands out as a platform for civic engagement, promoting new spaces of digital activism for three main reasons: the chat app (1) affords structurally new forms of political participation and collective engagement, (2) forges communities of mutual interest, and (3) promotes collective decision-making and individual autonomous actions on a small scale. However, drawbacks are found in howbots can influence conversations on WhatsApp, fake users can hijack chats, and group members may be threatened by surveillance attacks.

Bolsonarism: into the Brazilian political crisis

In 2019, the first year of Jair Bolsonaro’s government, Brazil has seen a record deforestation and a drop to zero applications of environmental fines. Bolsonaro nominated a human rights minister who was well-known for preaching sexual abstinence as a state policy. Sons of the president are under investigation of crime and corruption. Also, Bolsonaro has nominated a secretary of culture extolling Nazi propaganda. Moreover, every week the Brazilian “anti-president” openly attacks the press, and recently was considered the worst leader to struggle against the Coronavirus pandemic.

The political scenario in which Bolsonarism surges is widely recognized as reflecting a crisis of political representation and the widespread disbelief in politics and traditional parties. Bolsonarism can be understood as “a political phenomenon that transcends the figure of Bolsonaro and is characterized by an ultra-conservative worldview, returning to traditional values and nationalist and patriotic rhetoric”. Facing this scenario, an urgent question should be addressed: what is really happening to Brazilian democracy?

Looking back, looking forward

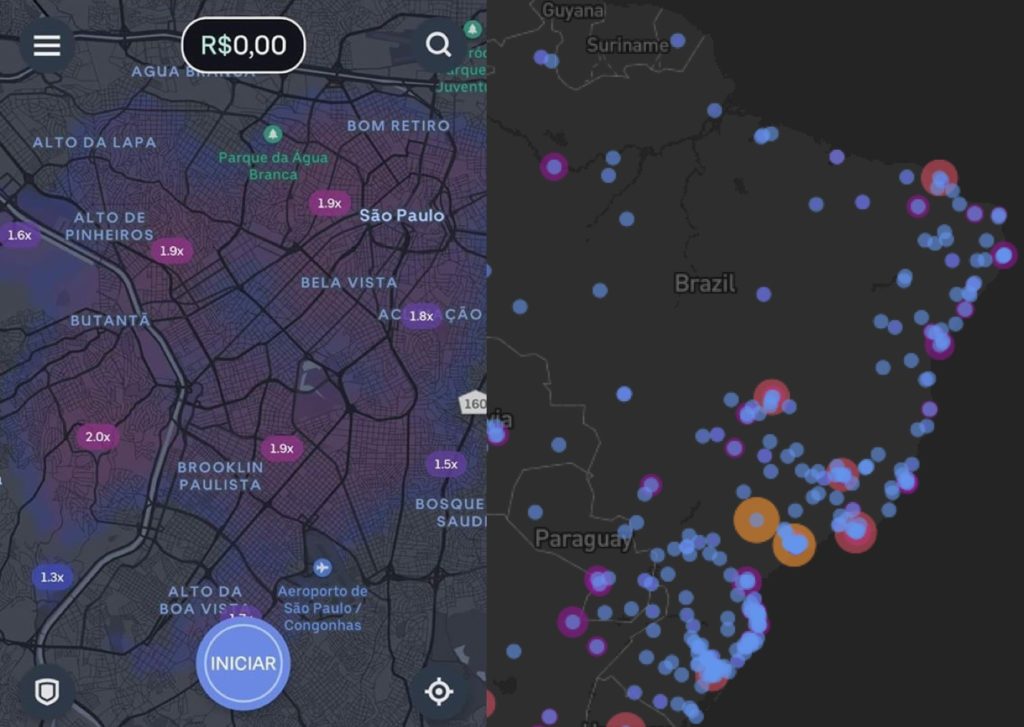

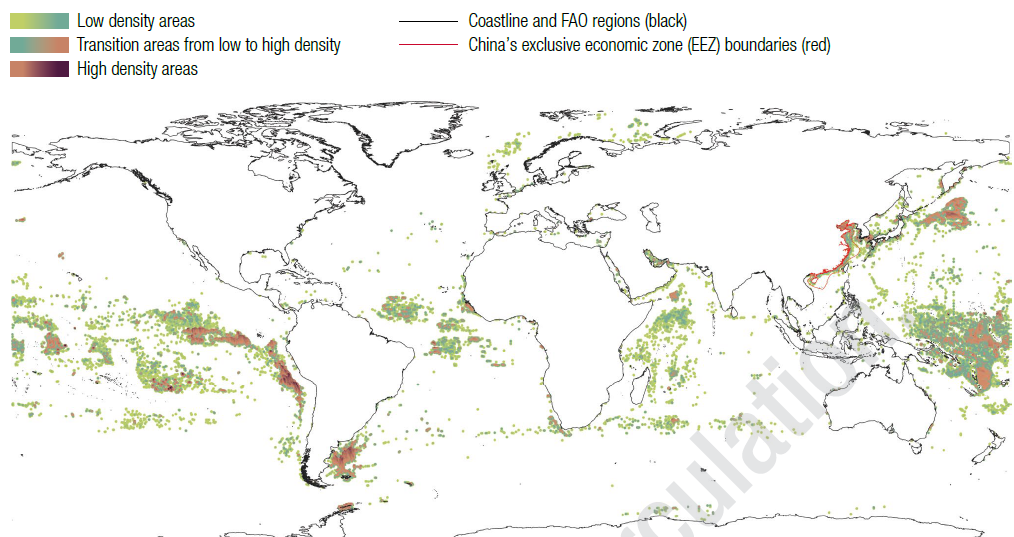

Brazil is an extremely unequal country along multiple dimensions that include internet access. Part of the semi-illiterate population gathers their information almost solely through visual messages, audios and videos from thousands of WhatsApp groups, thanks to the “zero rating” fees provided by telecom companies that replaced more expensive short-text messages. The larger context of Latin America makes an excellent test bed for the study of WhatsApp social interactions because “96 percent of Brazilians with access to a smartphone use WhatsApp as primary method of interpersonal communication”. According to the Reuters Institute, 53 percent of Brazilians use “ZapZap” (as the app is commonly known in the country) to find and consume news. Everyday citizens also use “ZapZap” to order pizza, stay in touch with family, transfer money, make doctor appointments, learn, spread gossip and date.

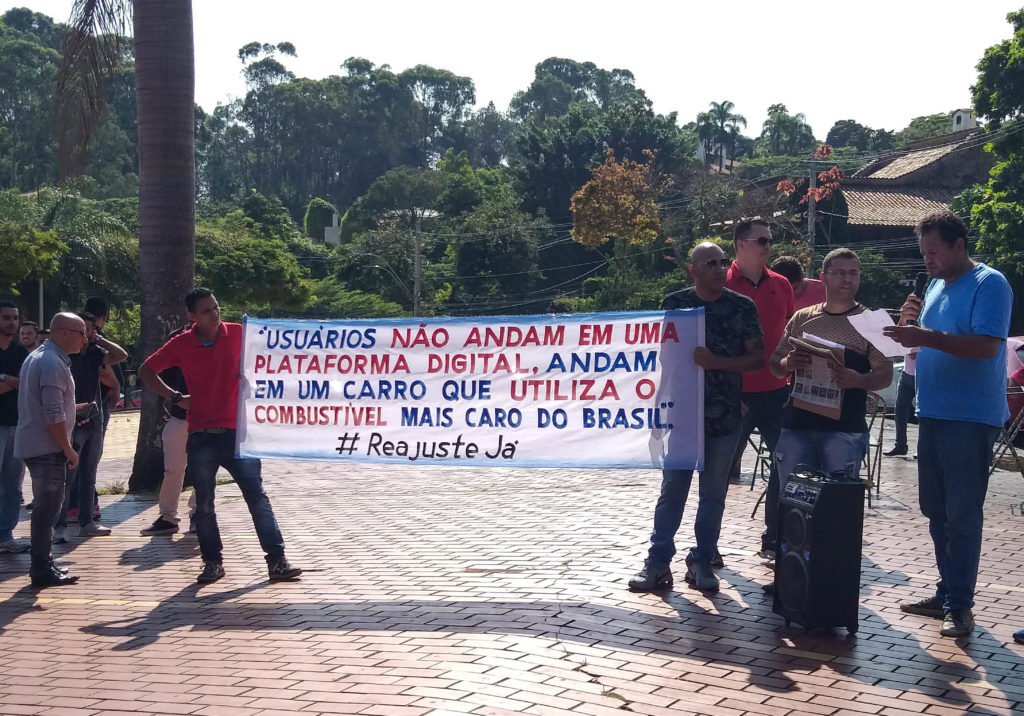

While the leftist “UCG” WhatsAppers were calling for political action, far right activists were articulating themselves in WhatsApp private groups and beyond, also combining online and offline activities. Progressive sectors were as well unable to build a national digital campaign, with very rare exceptions, such as small local initiatives like UCG. Consequently, the potential of digital activism on chat apps was later weaponized by far-right groups that not only appropriated public and private groups on and with WhatsApp, but also acted as pipeline to other social media. Digital information became a “weapon” that is still used in “out of control” mode nowadays by Bolsonaro’s supporters, taking advantage of the high penetration of WhatsApp in Brazil, and facilitated by the limited digital literacy of the population. In fact, Bolsonaro ran a successful campaign in 2018 based on a combination of bottom-up authoritarianism and digital populism. His supporters were helped by bots to spread misleading content “weaponizing” various WhatsApp groups.

COVID-19: creative WhatsAppers from the margins

This case presents important implications for the ongoing crisis. Brazilian citizens are currently bombarded with COVID-19 related disinformation and facing a chaotic portrait, while far right activists occupied larges spaces on digital networks before and after the 2018 elections. Moreover, there are lessons learned from the inability to stop Bolsonarism’s digital army, namely: send messages which everyday citizens can trust. Today, Brazilians behave more and more like consumers instead of citizens, trusting the market more than science – perhaps this is precisely the gap that paves our country for thousands of deaths during the coronavirus pandemic.

Brazilian mainstream media are currently discussing who might be a potential presidential candidate for the next elections in 2022. However, a deeper question is whether democratic values will still be upheld at that time. The composition of Bolsonaro’s government reminds us that Brazilian’s young democracy is now more capitalist, colonialist, patriarchaland is heading towards a dangerous and irresponsible political adventure, and the outcomes are unpredictable. During the pandemic, social distancing, hand washing, hand sanitizers, masks, respirator machines and lockdowns are privileges of the Global North, while in the South, many will not even have access to minimum services.

As the title suggests, using WhatsApp for chatting and hanging out alone will not solve the political Brazilian disarray, but perhaps creative WhatsAppers could provide a spark to create national-transnational solidarity. Namely: high speed participatory decision-making to deliver groceries, collect money, produce masks, share scientific information, mobilize against COVID-19 related disinformation, reach poor families and fight for emergent democratic imaginaries. The UCG case study still works as a well-informed internal communication strategy for connecting and activating social solidarity networks that grounds for hope, especially because it reveals the battlefield of political struggle that enables scientific shared information, civic engagement, collective mobilization, and solidarity. Lastly, the coordination of online activities combined with actions on the ground by WhatsAppers triggers digital activism in times of pandemic.

About the author

Sérgio Barbosa is a PhD candidate in the program “Democracy in the Twenty-First Century” in the Centre for Social Studies (CES), at the University of Coimbra and a Sylff fellow sponsored by Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research. He is a member of the Technopolitics – a “Latin” research network connecting Brazil and Ecuador with Spain, Portugal and Italy. His research explores the emerging forms of political participation vis-à-vis the possibilities afforded by chat apps, with emphasis on WhatsApp for digital activism and social mobilization

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Silvia Masiero for her careful review (and beyond) and wishes to thank Charlotth Back and Jeroen de Vos for their comments and suggestions. He extends his gratitude also to Stefania Milan and Emiliano Treré for launching Big Data from the South initiative. This blogpost has received funding from the Sylff (Ryoichi Sasakawa Young Leaders Fellowship Fund) Research Abroad – SRA fellowship sponsored by the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research.