O que acontece quando a cidade digital encontra desastres e pandemias em grande escala como o COVID-19? Este artigo analisa o caso de São Paulo, Brasil, para ilustrar como a pandemia contribui para enfatizar um amplo espectro de desigualdades. Na maior metrópole da América Latina, a população experimenta com uma forte disparidade de condições socioeconômicas e culturais, ao mesmo tempo em que grupos marginalizados sobrevivem entre os maiores riscos da pandemia, com condições precárias de acesso e uso da Internet. Como resultado, um “vírus da desigualdade” ecoa com a pandemia.

Por Larissa G. de Magalhães

Nas últimas duas décadas, a proliferação de tecnologias digitais apoiou um processo ambicioso de digitalização de ecossistemas urbanos complexos, incluindo as de megacidades como São Paulo (Brasil). Mas o que acontece quando essa tendência se choca com desastres e emergênccias em massa como o COVID-19? Esses momentos de intensa crise representam um ponto de virada na governança dos habitats urbanos, expondo a urgência da capacidade de resposta baseada em dados, apoiada pelos avanços da tecnologia.

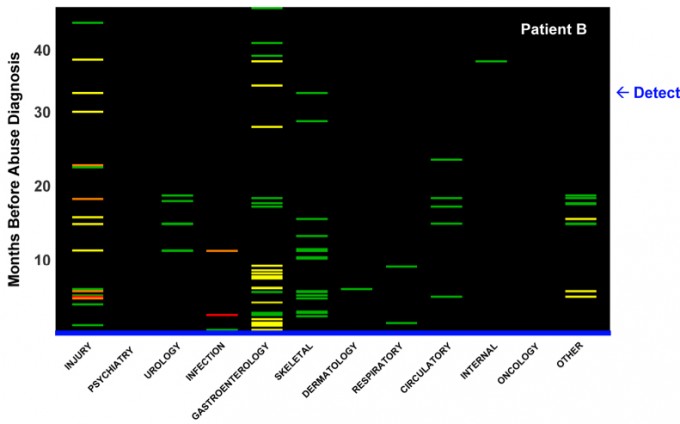

Durante situações de crise, ferramentas analíticas e técnicas de aprendizado de dados podem apoiar os tomadores de decisão com grandes quantidades de dados, por exemplo, acionando alertas e ajudando os governos a identificar as principais linhas de frente. No entanto, no mundo em desenvolvimento, grandes setores da população permanecem excluídos da esfera digital, e mesmo projetos de dados abertos liderados pelo governo podem levar à sub-representação de certos grupos . À medida que muitos desses países se tornam cada vez mais ativos on-line, é provável que as desigualdades, incluindo o fosso digital, comprometam as tentativas de usar dados para melhorar a qualidade de vida dos cidadãos. Os padrões de desigualdade das megacidades, em particular, revelam que as desigualdades sociais, econômicas, culturais e digitais ainda são um desafio grave na definição das melhores estratégias para combater crises que afetam toda a população.

Este artigo analisa o caso de São Paulo, Brasil – a cidade mais populosa das Américas, com seus 12 milhões de habitantes – para explorar como as oportunidades de acesso e uso da Internet no centro do projeto da cidade digital seguem o padrão desigualdades estruturais, contribuindo, em última análise, para reforçá-las. Essas desigualdades afetam mais severamente os lares e famílias nas áreas mais periféricas e mais pobres da cidade.

Segregação digital e a cidade

Durante emergências, os tomadores de decisão podem ser inundados com dados. De acordo com a OCDE (2019), no entanto, as lacunas de dados causadas pelas desigualdades existentes podem criar problemas para aqueles afetados por políticas criadas por bancos de dados incompletos ou sub-representativos. Outro problema é o uso de sistemas automatizados para coletar dados , especialmente de grupos que podem ter um rótulo menos confiável do que as maiorias, devido à presença “incorporada” na rede.

Como a tomada de decisões com base na falta de dados pode negligenciar as linhas de pobreza traçadas na paisagem urbana, isso pode desencadear custos de sobrevivência mais altos em áreas já marcadas pela segregação social . É durante emergências de larga escala como o COVID-19 que essas lacunas de dados se tornam particularmente problemáticas porque as desigualdades levam os menos privilegiados ao mais alto nível de risco para o vírus, e levam às piores conseqüências socioeconômicas da pandemia.

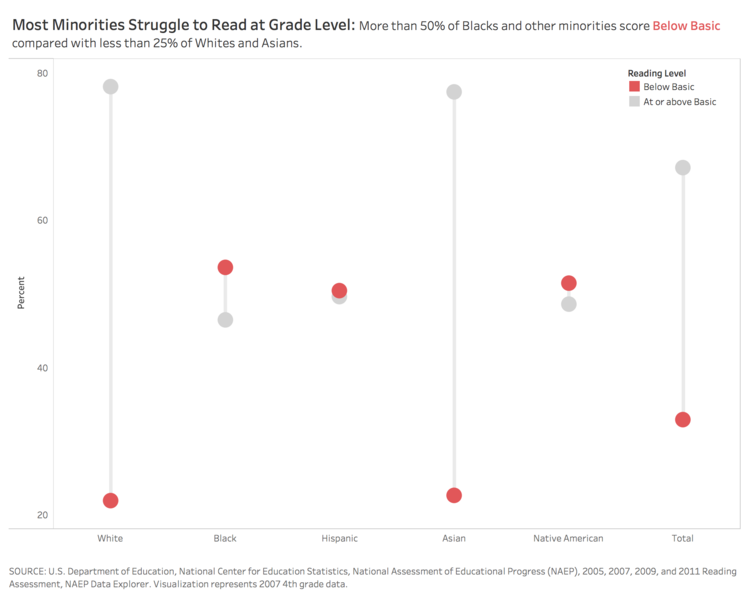

A geografia digital do país indica um panorama de desigualdades em relação ao uso da Internet , embora nos últimos 15 anos o acesso à Internet tenha atingido 70% dos domicílios . Por um lado, o Brasil avançou na criação de leis, normas, políticas e práticas projetadas para abrir dados , como a criação da Infraestrutura Nacional de Dados Abertos , a Lei de Acesso à Informação , a Estrutura Civil da Internet , a Política de Dados Abertos , Política de Governança de Dados , Estratégia Digital do Governo e a implementação do 4º Plano Nacional de Parceria com a Parceria Aberta do Governo . Por outro lado, no entanto, continua a haver uma estratificação digital no país que coincide com as desigualdades na distribuição de renda e que se reflete na escassa capacidade de ser parte ativa na economia digital e na produção formal de dados. O custo da banda larga é outro fator que afeta as desigualdades de acesso, com as áreas rurais ou perifericas sendo penalizadas; Além disso, os níveis de literacia digital e acessibilidade da Internet são baixos.

Na região metropolitana de São Paulo, que conta com 12 milhões de habitantes, a conectividade é superior à média nacional, atingindo 79% dos domicílios . Porém, somente a conectividade, no entanto, não é suficiente para garantir que as pessoas possam se beneficiar da Internet. Além disso , a Internet é relevante quando as pessoas têm as habilidades e a confiança necessárias para usá-la . Em São Paulo, as oportunidades de acesso e uso da Internet aparecem segregadas no território urbano, seguindo o padrão das desigualdades estruturais existentes. Isso sugere que, no caso de São Paulo, as desigualdades relacionadas ao mundo digital são condicionadas pela matriz de vulnerabilidades que afetam famílias e domicílios no território urbano, onde os padrões observados reproduzem desigualdades intra-urbanas.

O “vírus da desigualdade”

Nesse cenário, a pandemia exacerba as desigualdades existentes. Um exame mais detalhado da desigualdade e do acesso à Internet mostra como os arredores de São Paulo são o epicentro da propagação de outro vírus ao lado do COVID-19, que podemos chamar de “vírus da desigualdade”. Dados do grupo de pesquisa independente COVID-19 Observatory indicam que na cidade, as pessoas de cor têm 62% mais chances de morrer do que os brancos. Se olharmos para o mapa de mortes confirmadas ou suspeitas de coronavírus nos distritos de São Paulo, há uma clara sobreposição de desigualdades, ou seja, quanto mais ampla a matriz de vulnerabilidade social, maior a letalidade do vírus. O risco de morte por COVID-19 é maior nas regiões Leste, Norte e parte das regiões Sudeste, onde também são os distritos com maior número de mortes por COVID-19: Brasilândia e Sapopemba, entre os distritos menos desenvolvidos da região. cidade.

Caso contrário, grande parte das regiões Sul (centro expandido), Centro-Oeste e Sudeste, com maior renda per capita, atualmente apresenta taxas de mortalidade padronizadas abaixo da média municipal . No entanto, as condições de moradia são um fator extremamente relevante, uma vez que os bairros centrais que concentram cortiços, aposentadorias e pessoas em situação de rua têm um número significativo de mortes. Em suma, o endereço residencial contribui para definir o impacto do coronavírus, sua gravidade e letalidade, pois é indicativo de outras desigualdades persistentes e destrutivas.

Segundo a Secretaria Municipal de Saúde, em 30 de abril, houve um aumento de 45% nas mortes nos 20 distritos mais pobres da cidade . O número também pode refletir a distribuição discrepante de unidades de terapia intensiva na cidade, uma vez que 60% dos leitos do Sistema Público de Saúde estão concentrados nas regiões mais ricas e centrais da cidade.

Rumo a um regime sociogital pós COVID-19

O que mais o futuro próximo traz para megacidades como São Paulo ? Uma nova abordagem à governança baseada em dados, que podemos chamar de regime sociodigital , provavelmente será estendida aos países do sul. A pandemia mostrou como estamos vivendo uma nova ordem social, que combina recursos que facilitam o acesso físico às tecnologias da informação e comunicação – infraestrutura de acesso à Internet e habilidades e habilidades digitais no nível individual. Essas combinações geram capital digital . Como os governos não criam políticas ou incentivos para a infraestrutura de acesso ou a alfabetização digital, há um esvaziamento do capital digital. Esse déficit é impulsionado pelas desigualdades estruturais que caracterizam um regime sociodigital. Em particular, na corrida para criar plataformas de vigilância para epidemias e sistemas de previsão de emergência, os sistemas de inteligência artificial (IA) “produzem” evidências políticas projetadas a partir da agregação dos chamados big data e outras formas de informações produzidas pelo governo . No entanto, os grupos marginalizados e os excluídos digitalmente continuam a sobreviver dentro das margens impostas pelos regimes sócio-digitais. O risco de reproduzir e perpetuar desigualdades nos ambientes altamente tecnológicos do futuro é real e não deve ser subestimado. Grupos marginalizados sobrevivem em uma complexa matriz de vulnerabilidades, variando das dimensões econômica, social e jurídica às dimensões cultural, digital e política. O risco é que dados ausentes ou mesmo dados mal utilizados se tornem mais um subproduto da desigualdade.

Vários estudos indicam que grupos marginalizados produzem menos dados , pois não estão envolvidos em atividades de geração de dados, não estão representados na economia formal, têm acesso desigual e menor capacidade de se envolver on-line. Portanto, enquanto mais dados estão disponíveis para projetar políticas e soluções, e para que os formuladores de políticas incluam demandas e grupos sociais historicamente excluídos, os dados acabam reproduzindo os padrões de discriminação e exclusão presentes no mundo digital, resultando em políticas públicas potencialmente discriminatórias. Ou seja, ter muitos dados não significa necessariamente que os dados sejam representativos e confiáveis ou que os governos possam usá-los.

Então, o que o padrão de desigualdade observado em megacidades como São Paulo nos diz sobre o futuro dos regimes sociodigitais iminentes? Reduzir as desigualdades nos centros urbanos é um desafio global, especialmente no contexto atual em que dados e tecnologias são combinados com possíveis soluções de emergência resultantes de desenvolvimentos como mudanças climáticas, desastres tecnológicos e pandemias. Mas as desigualdades no acesso e uso da Internet revelam a importância contínua da luta por direitos e acesso a bens, serviços e oportunidades de qualidade.

Embora coexistam múltiplas desigualdades, as luzes lançadas pelas desigualdades digitais refletem a falta de políticas públicas efetivas e eficientes para todos. O mundo digital reproduz os modelos de negócios da economia física, reforçando as lacunas existentes no acesso aos benefícios. Espera-se que o fim do isolamento também seja o fim do isolamento dos pobres, negros e desajustados nas cidades. As cidades estão engajadas na construção de soluções para o rescaldo do COVID-19, que convida a intervenções em educação, saúde, infraestrutura, participação, colaboração e transparência pública. A construção de capacidades digitais e responsabilidade compartilhada deve ser uma característica duradoura dos governos nas cidades.

Sobre o autor

Larissa é PhD em Ciência Política pela Unicamp, jovem pesquisadora e consultora em políticas públicas, governança e dados abertos. Ela é pesquisadora de pós-doutorado associada ao programa CyberBRICS da Faculdade de Direito da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, e analisa a infraestrutura de acesso à Internet, políticas digitais, impactos de tecnologias e inovação nos países em desenvolvimento e no sul global.