Out of Reach: Distance Learning in Peruvian Rural Areas During the Pandemic This blog post aims to analyze the actions carried out by the Peruvian government regarding distance education and contrast them with the uses and practices of technology in Andean rural communities. Likewise, it problematizes digital inclusion and exclusion that is reflected through the digital divide: who is included and who is excluded from the Peruvian public school in the new normal setting.

Por Karla Zavala Barreda

La cuarentena y las medidas de distanciamiento social han afectado el desenvolvimiento de las actividades escolares a nivel nacional. En marzo, luego de aplazar el inicio del año escolar por dos semanas, el Ministerio de Educación desplegó el plan de enseñanza a distancia ‘Aprendo en Casa’. La estrategia, a través de señal televisa y radial abierta, busca reemplazar la educación presencial a través de sesiones de aprendizajes adaptadas a dichos medios. La difusión del contenido también se apoya de las radios comunitarias. No obstante, esta estrategia no incluye a los centros poblados, donde hay un nivel muy bajo de conectividad, y donde se encuentran comunidades que están fuera del alcance de la señal de los medios masivos y de la cobertura de internet.

En el Perú, la educación rural tiene un modelo de alternancia donde los estudiantes asisten intermitentemente a clases. Luego del anuncio del inicio de la cuarentena obligatoria, dichos estudiantes regresaron a sus hogares, los cuales en muchos casos no cuentan con medios o conectividad para acceder a los contenidos de Aprendo en Casa. Cabe preguntar entonces, ¿cuál es el estado de los estudiantes en comunidades rurales en el país que ha implementado una de las cuarentenas más estrictas a nivel mundial?

Educación a Distancia en Zonas Rurales

Frente a esta problemática de acceso al contenido escolar, se anunció la adquisición de un millón de tabletas a ser repartidas a los estudiantes y maestros de áreas rurales clasificadas en los quintiles 1 y 2 de pobreza. En este contexto, cabe recordar que el gobierno peruano ha implementado desde hace treinta años programas de compra equipos informáticos en el sector educación, tales como Una Laptop por Niño, proyecto Huascarán, Jornada Escolar Completa, entre otros. Sin embargo, estas adquisiciones no ayudaron a amortiguar la necesidad de educación a distancia que emergió durante esta crisis sanitaria, convirtiéndose así en el gran elefante blanco del que poco se ha discutido.

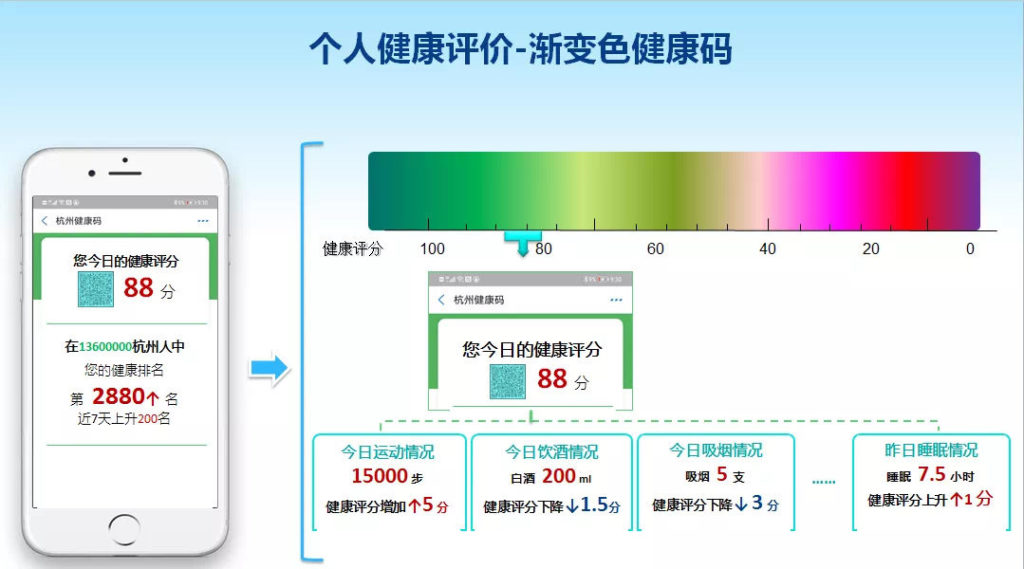

Asimismo, la solución ofrecida para acortar la brecha de conectividad de las zonas rurales es la inclusión de tabletas con chip y cargadores solares. Pero sin señal satelital de internet en el área donde usarán la tableta, el chip no podrá conectarse a ningún lado. Esta coyuntura es un recordatorio de la materialidad de la infraestructura digital. Depende de cables, de satélites, de proveedores y operadores para que la señal llegue a quienes están fuera de alcance. La brecha digital entre zonas urbanas y rurales es abismal. La conectividad en áreas rurales no alcanza más del 20%, a esto se suma que el servicio ofrecido es de baja calidad, y la velocidad de conexión es lenta.

Al implementar el aislamiento social obligatorio, las zonas rurales fueron expuestas a un grado mayor de vulnerabilidad al no contar con infraestructura y conectividad en sus hogares. Esta situación se agrava en un país donde el gobierno apenas conoce a la realidad de la población. Mientras el Ministerio de Educación señala que el 94% de los estudiantes escolares está accediendo a los contenidos de Aprendo en Casa, la Defensoría del Pueblo –institución nacional que defiende y promueve los derechos de las personas y la comunidad– indica que en provincias el poco acceso a educación durante la pandemia ha incrementado el número de deserción escolar. Por ejemplo, en Cerro de Pasco, más de 7000 estudiantes no acceden a la educación a distancia. Situación similar ocurre en una de las regiones más pobres del país, Huánuco, donde más del 30% de escolares tampoco cuenta con acceso.

Prácticas desde la Periferia

A casi dos meses de la clausura del año escolar, las tabletas aún no llegan a los destinatarios. Y aunque llegaran, la distribución de dichos dispositivos no resolverá las dificultades de conectividad y acceso a información. Es en este escenario donde acciones como las del alcalde de Corani, localidad de Puno, al sur de país, llaman la atención, no solo porque contrató la instalación antenas satelitales para brindar conexión a cinco comunidades rurales en extrema pobreza, sino por el razonamiento detrás de esta acción: proveer acceso libre a internet. Mientras los sistemas digitales continúen absorbiendo y embebiendo actividades sociales, la infraestructura de conexión efectivamente determina y restringe cómo los usuarios se comunican y acceden a información. Es por estas razones que el acceso a internet se ha declarado como un derecho humano, ya que no solo ayuda a difundir contenidos educativos sino también a acceder a servicios del estado sin necesidad de desplazamiento geográfico, y conocer los derechos.

Al optar por la transmisión de sesiones de aprendizaje a través de medios de comunicación e internet, el gobierno peruano no garantiza el derecho de acceso a la educación a quienes no cuenten con los medios necesarios para acceder a dicho contenido. Al condicionar dicho acceso, se incrementa la vulnerabilidad de poblaciones rurales en extrema pobreza. En contraste, lo sucedido en Corani no solo beneficia a los estudiantes, sino también a los miembros de la comunidad, que pueden acceder a información respecto a los bonos repartidos durante la pandemia, y también a los estudiantes universitarios o de carreras técnicas, que gracias a este servicio pueden conectarse a sus clases virtuales.

A la vez, se hace frente a una problemática que pasa desapercibida: la compra de paquetes de datos móviles. Durante la cuarentena, miembros de comunidades rurales adquieren semanalmente paquetes de datos para que sus hijos puedan acceder a la educación a distancia. Imágenes de niños buscando señal en la cima de las montañas se han compartido en las redes sociales sin cuestionar quién cubre el costo de esa conexión. En otras palabras, la educación que antes era gratuita se constituye como un costo adicional al estar mediada.

Por otro lado, nuevamente la materialidad de los contenidos digitales necesita ser abordada. Internet no está compuesta de solo bits y señales que fluyen de manera invisible en el aire. El contenido audiovisual demanda el uso muchos datos móviles, y a su vez esta transmisión de datos depende de infraestructura que provea conexión. Si contrastamos la penetración de celulares se puede observar que más de un 85% de hogares rurales cuenta con un dispositivo móvil (INEI, 2020). Sin embargo, solo un 5.9% tiene acceso a internet. Poniendo este dato en el contexto actual y los retos que el distanciamiento social presenta, cabe cuestionar qué tanto se toman en consideración los celulares en la difusión, diseño, y desarrollo de la educación a distancia. Por ejemplo, si el ancho de banda no es óptimo, ¿hay versiones lite (bajo uso de datos, poco uso de imágenes, etc.) de las páginas y apps educativas? ¿Por qué no se toma política de mobile-first como en otros países?

Estos interrogantes abren el diálogo para dejar de privilegiar la adquisición de tecnología de punta y el uso de nuevos medios en estrategias nacionales sin tomar en cuenta el ensamblaje socio-técnico que permite la conexión a Internet. En el Perú hay muchas áreas que siguen fuera de alcance, y no es coincidencia que sean los mismos espacios geográficos donde se encuentran las comunidades rurales. Por otro lado, decisiones como la compra de tabletas sin una propuesta íntegra hace evidente la falta de planes sostenibles en el tiempo para la implementación de iniciativas tecnológicas, que si bien buscan cerrar las brechas digitales, no parecen tomar en cuenta la realidad de las diferentes regiones del país.

Karla Zavala Barreda holds an MA in Media Arts Cultures, and is a PhD student at University of Amsterdam in the Department of Media Studies. Her research focuses on software studies, interface criticism, game studies, algorithmic literacy, and critical design. She is interested in the intersection between software, design, and education. She tweets at @karlazavala.