By Niels ten Oever

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, people wondered whether the internet infrastructure would be capable of handling the increase in data traffic. When many people started working, streaming, and following the rapidly unfolding news on social media from home, many expected this would strain on the internet infrastructure. Some European politicians were so concerned that they called on Netflix to lower the resolution of their video streams. Why did it turn out the internet infrastructure was able to cope with the increasing demand? The answer is, because the internet no longer works as most people think it does. An extra layer of control was added to the internet by Content Delivery Networks. This chapter will discuss how pressure on the infrastructural margins of the internet is strengthening the center of the network, and examine how COVID-19 has exacerbated this trend.

In 2011, the Tunisian government started heavily censoring the internet in response to popular uprisings in the country. In response, many internet users engaged in what is commonly called a Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attack on the Tunisian government’s website. In a DDoS attack, hundreds or even thousands of computers try to reach a website at the same time. This can lead to the website’s server, or the connection to the server, being overloaded and thus render the website unavailable to internet users. When a website suddenly becomes very popular, this can also lead to similar behavior. When many users try to connect at the same time, the traffic effectively renders the site or service unavailable. Eight of Tunisia’s websites were forced offline.

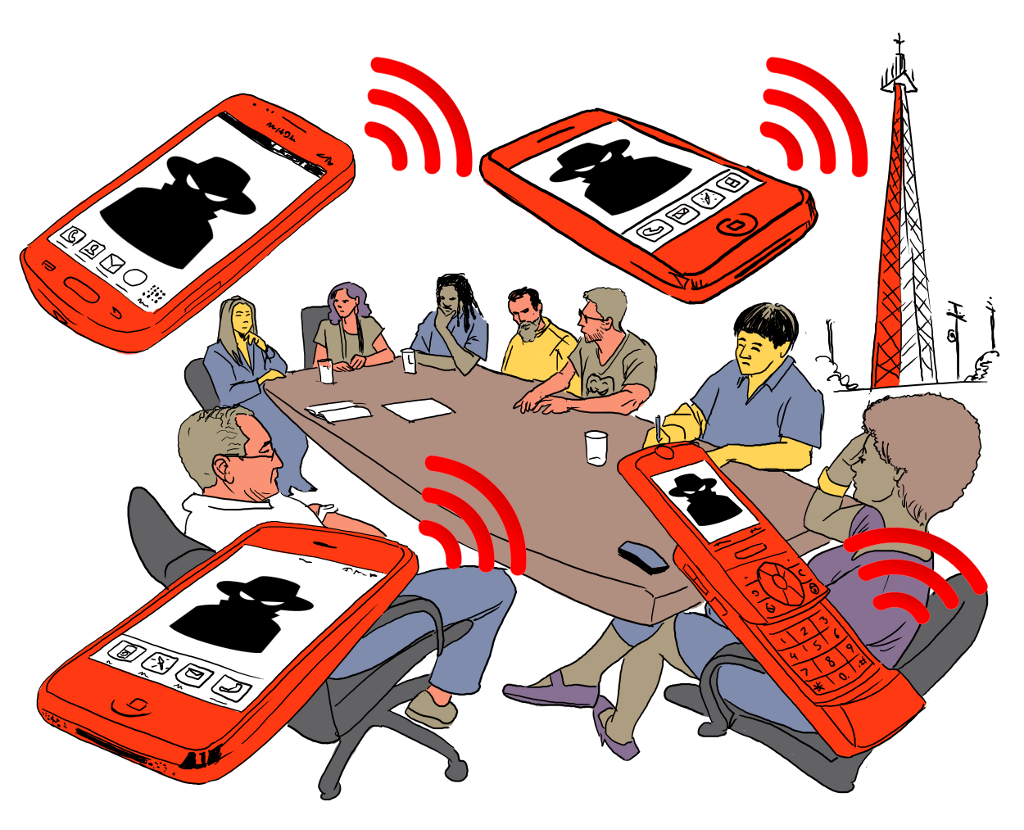

In response to the DDoS attacks, and to prevent down-time of servers due to their popularity, Content Distribution Networks (CDNs) were increasingly used. CDNs are globally-distributed proxy servers, often placed in data centers close to internet eXchange Points (IXPs). While a user thinks they are connecting to a popular website far away, they are connecting to a CDN server that is located near them. While you are thinking you are streaming a video from a jurisdiction that you think is safe, the video is more likely to be stored close to the network controlled by your Internet Service Provider (ISP) or your telecommunications operator.

When the internet was designed, an engineer adopted the end-to-end principles as their central motto. This was included in the mission statement of the Internet Engineering Taskforce, the institution responsible for co-developing and standardizing the internet infrastructure:

The Internet isn’t value-neutral, and neither is the IETF. We want the Internet to be useful for communities that share our commitment to openness and fairness. We embrace technical concepts such as decentralized control, edge-user empowerment and sharing of resources, because those concepts resonate with the core values of the IETF community. These concepts have little to do with the technology that’s possible, and much to do with the technology that we choose to create (RFC3935).

When users connected to the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic, it may seem they were edge-users connecting to another endpoint over “dumb pipes”—leveraging the powers of decentralized control. The truth it quite the opposite. The internet infrastructure held up during the COVID-19 pandemic not because people were getting their content from the global internet, but from a data center near them. You may think is actually a good thing, since it caused the internet to not collapse? Maybe. CDNs are the mere latest cause and consequence of centralization on the internet. The difference between CDNs and other large players such as Google and Facebook (who have their own CDNs) is that these other CDNs remain largely invisible. Some of you might have heard about Cloudflare, but what about Akamai, Fastly, and Limelight?

In 2017, Cloudflare unilaterally removed the neo-nazi forum and website Daily Stormer from its services. In 2019, it similarly removed the imageboard 8chan after two shootings in the United States. The company cited the following reason for removal: “In the case of the El Paso shooting, the suspected terrorist gunman appears to have been inspired by the forum website known as 8chan. Based on evidence we’ve seen, it appears that he posted a screed to the site immediately before beginning his terrifying attack on the El Paso Walmart killing 20 people”. The interesting point was that no one asked Cloudflare to do this; they removed the content on their own volition, without a clear process in place. Many critical internet scholars such as Suzanne van Geuns, Corinne Cath, and Kate Klonick have reported on this. While such decisions show the concrete impact these companies can have, it is perhaps even more telling that one hears very little about these companies.

CDNs are perhaps the internet infrastructure that companies benefitted most from during the COVID-19 epidemic, because there was increased traffic to the websites that they provide services to. But what about the people who requested information from these websites? Technically, they got served by another server than the one they thought they were connected to. They might have received something else than what they asked for, because CDNs allow for particularly fine-mazed geography-based adaptation of content. The CDN that served a user in Senegal might have different data than a CDN that served a user in Brisbane. And there is almost no way of knowing by which particular CDN server you got served, or to bypass the CDN. In this way, the opacity of internet infrastructure was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic led to further black-boxing of the internet infrastructure, making it harder for users to understand how it works. While this might make the internet faster and more available, it does not make the internet more reliable. Arguably, it makes the internet a better tool for control, because it increases power asymmetries between users and transnational corporations.

In 2011, Tunisian internet users were able to use the internet infrastructure against their own government. In 2020, it is nearly impossible for users around the world to even know where the websites they are accessing are located, let alone take them down. The internet is no longer a bazaar. The COVID-19 pandemic helped fortify an industrial zone that now is the internet, which only allows users to connect on the outside, without having a view or control on the inside. The internet has become a smart network, with not so smart edges.

Niels ten Oever is a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) and Texas A&M University (USA), associated also with the Centro de Tecnologia e Sociedade at the Fundação Getúlio Vargas, Brazil. His research focuses on how norms such as human rights get inscribed, resisted, and subverted in the Internet infrastructure through transnational governance. Previously, Niels has worked as Head of Digital for ARTICLE19 and served as programme coordinator for Free Press Unlimited. He holds a cum laude MA in Philosophy and a PhD in Media Studies from the University of Amsterdam. He sometimes