By Anna Berti Suman – Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society (TILT)

During the Workshop ‘Big Data from the South: Towards a Research Agenda’, we discussed how the ‘South’ is much more than a geographical connotation. The South exists every time a person is discriminated, basic services are denied, surveillance is secretly performed at the expenses of those at the margins, land, but also data, are grabbed for the sake of profit, people are forced to daily live with environmental contamination, and so on. In this sense, maybe the South is not geographical at all, if we think that all these situations can well occur in the North as in the South of the world. This contribution tells a story ‘from the South’: the South of Italy (yet a country generally considered as part of ‘the North’), and a situation embedding the South through denial of rights and resource appropriation. But it also tells a story of hope, of civic resistance that can make a change, speaking to individuals, collectives, and even to institutions, with a tireless critique of the status-quo.

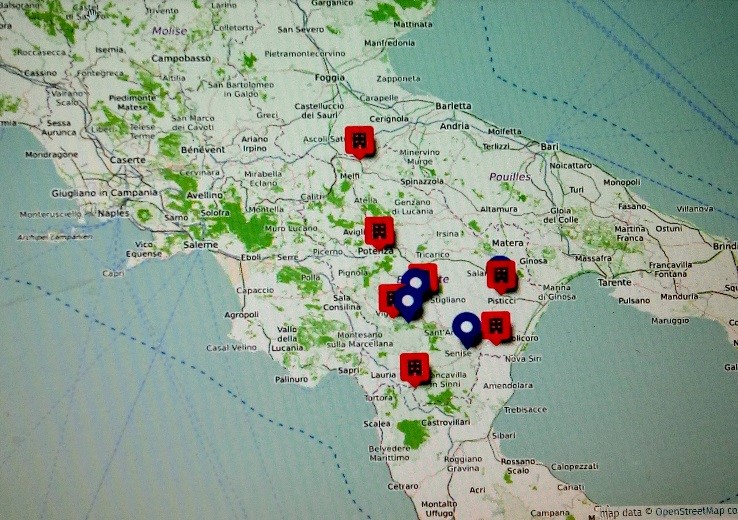

The case is that of ‘AnalyzeBasilicata’ (in Italian ‘Analizziamo la Basilicata’), founded in 2015 by the Italian association ‘COVA Contro’ and aimed at tackling the environmental mismanagements in a Southern Italian region, Basilicata, known for having a 40% of the population at risk of poverty. The region is also sadly known as “the Italian Texas” for the intense oil exploitation and its incidence on local residents. The ‘AnalyzeBasilicata’ initiative started as a campaign and quickly obtained a vast social uptake, manifested in the generous financial support from concerned citizens. Through crowdfunding, AnalyzeBasilicata managed to buy the necessary instruments to collect sample in numerous areas of the region and run chemical tests at the premises of Accredia, the Italian single body for scientific accreditation. The results of the test fuelled investigations that were subsequently published on the online magazine Basilicata24. The initiative currently strives to make publicly accessible the data from the measurements on its website as well as the sources of funding to support such measurements. In addition, the organization has barely any organizational structure, devoting all the resources obtained from crowd-funding to the measurements.

The collective’s workflow is structured as follow: when the AnalyzeBasilicata team identify an environmental problem, they run a cross-check or alterative measuring on the interested area; if they find a discrepancy between the official data and their measurements, they either first publish the news on their blog and then file a formal notification to the competent environmental agency or to the public prosecutor office, or, in alternative, they first notify the problem to the relevant institutions and then reach the public. The choice of one or the other strategy depends on the matter at issue, its sensitivity and public concern. In general, the response from the concerned citizens is higher than the interest and follow-up from the responsible institutions [1]. The collective works either spontaneously or in response to a request from a group of concerned citizens. Rarely, they are approached by institutions requesting measurements [2]. The individuals running the tests are, for the majority, not experts in environmental monitoring. However, they trained themselves, and benefit from the help of experts on how to collect sampling and analyse data [3].

Examples of the actions launched by the COVA Contro Association and AnalyzeBasilicata regard to the correlation between the ENI and INGV extractive operations in the region and the seismic status of Val d’Agri, Basilicata. The collective interestingly mentioned the Aarhus Convention when denouncing the lack of transparency and public participation on the matter to the Italian environmental protection agency, ISPRA, to the Italian anti-corruption agency, ANAC, to the Public Prosecutor’s Office and to the National Anti-Mafia Directorate. The reliance of the local collective’s discourse on entitlements deriving from an international legal body is particularly relevant as it demonstrates how the local needs to ‘rely on the global’ to strengthen its arguments, yet resting strongly grounded in the local dimension.

Another timely intervention of the collective is represented by the analysis performed in the area of Policoro, Basilicata, where the civic monitoring, originally looking for traces of trihalomethanes in drinking water (which were instead found under threshold), discovered traces of two halogenated compounds that are recognized to have carcinogenic effects. The tests were run as cross-check of those performed by the competent authorities. The organization lamented the unfulfilled duty of public authorities to ensure that drinking water are preserved free from pollutants, thus including not only the substances provided by the Italian legislative decree 31/2001 but all substances possibly noxious to human health. This way the collective showed to be aware of the legal framework and to ground its claim on institutionally recognized legal entitlements, partially covered by the right to live in a healthy environment. The organization demanded a legal intervention by asking for the definition of clear maximum thresholds for the presence of the toxic carcinogenic compounds in drinking water. This approach is also particularly noteworthy as it shows that civic resistance still need to ‘use’ the system, while resisting it, and the appeal to legal provisions seems a way to find a form of recognition in the establishment.

The founder of AnalyzeBasilicata, Giorgio Santoriello [4], affirmed that the trigger for the launch of the initiative was the distrust towards the data provided (often scarce or difficult to access) by the environmental agency responsible for the territory. Santoriello described how the agency was unequipped and lacking personnel. From a first stage of ‘shadowing’ what the agency was doing to monitor the environmental conditions of the area, they started performing the monitoring themselves, comparing the two and identifying discrepancies. The first accreditation, according to Santoriello, was the social support from the concerned citizens through financial support and follow-up on media. Despite being critical towards the established way of environmental monitoring in Basilicata, the collective has always been willing to cooperate with the prosecutor offices, environmental agencies and politicians to shed light on the malfunctions of the environmental governance system in the region. This ‘open’ approach is also worth of reflection: the collective challenges the system, but it is ready to engage in a dialogue with established institutions in view of the ultimate goal, i.e. the improvement of environmental protection in Basilicata.

Despite relying on legal norms, Santoriello seemed to suggest that the laws on transparency and public accountability, as well as those on civic access to environmental information and participation in environmental decision-making, are insufficient to concretely enforce citizens’ rights. First, they would be too soft, not providing for actual sanctions. Second, their enforcement in courts would require high financial resources that often citizens’ organizations lack. Thirdly, they are often applicable only in cases of plain violations, and not in the daily subtler instances of citizen’s misinformation or of inaccessible information. Santoriello identifies in citizen-run technologies a light of hope to tackle the problem of poor environmental monitoring or hidden environmental data. He considers nowadays more pressing than in the past the need to use technology to draw the link between environmental pollutants and human health. Santoriello stresses the centrality of having ‘doubting’ citizens that crosscheck the environmental information received as a way to improve environmental monitoring, to ensure the respect of fundamental rights and to promote accountability.

Overall, this accountability outcome seems resulting of a combination of the following elements: distrust towards environmental (mis)management generates a civic initiative based on citizen-run technologies; the collective gains credibility (activists obtain scientific accreditation for their measurements); by cross-checking institutional data, the group manages to demonstrate substantial deviation from a proper environmental management; the collective obtains attention of larger sections of society; they justify their actions based on norms but simultaneously discard them; ultimately, though just a ‘drop in the ocean’, a push towards more transparency and accountability is activated.

Anna Berti Suman – is a PhD researcher at the Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society (The Netherlands), investigating forms of environmental monitoring ‘from below’. Anna has work and research experience in environmental crimes (Ecuador) and water conflicts (Chile); Anna is pro-bono environmental lawyer for Greenpeace International.

You can reach her at: a.bertisuman@uvt.nl

[1] Call performed on September 24, 2018, with the founder of ‘AnalyzeBasilicata’, Giorgio Santoriello.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Ibidem.