Author Monika Halkort

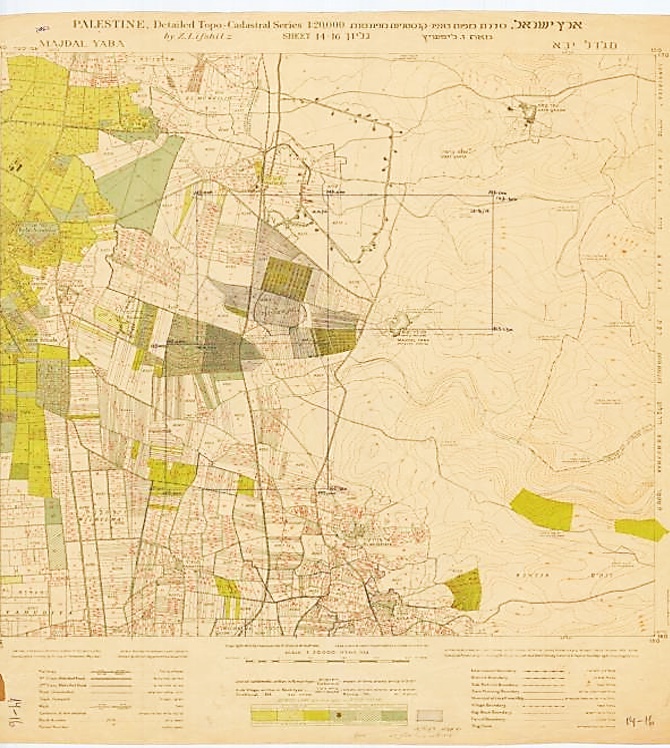

In this twofold blogpost (1/2), guest author Monika Halkort complicates the notion of ‘data colonialism’ as employed in The Cost of Connection by Nick Couldry & Ulises Mejias (2019a), drawing on a case study of early datafication practices in historical Palestine. This blogpost is one out of two: the first contextualizes ‘the colonial’ in data colonialism, the second draws on the casestudy to argue for the need to reimagine data agency in times of data colonialism.

One of the underlying themes running through the workshop Big Data from the South: Towards a Research Agenda was the question how to characterize our relations with data, focusing specifically on the geo- and bio-politically context of the Souths. Our working group took up the critical task of reviewing the concept of ‘data colonialism’ to discuss whether it provides a productive framework for understanding forms of dispossession, enclosure and violence inhered in contemporary data regimes. Nick Couldry and Ulises Mejias (2019a), both participants in the workshop, make precisely this point in their new book “The Cost of Connection” where they argue that the unfettered capture of data from social activities and relations confronts us with a new social order – a new universal regime of appropriation – akin to the extractive logic of historical colonization. (Find Ulises Mejias’ recent blogpost on decolonizing data here.)

Data colonialism, in their view, combines the predatory extractive practices of the past with the abstract quantification methods of contemporary computing. This would ensure a seemingly natural conversion of daily life converges into streams of data that can be appropriated for value, based on the premise of generating new insights from data that would otherwise be considered to be noise. Thus, while data colonialism may not forcefully annex or dispossess land, people or territories in the way historical colonialism did, it nonetheless relies on the same self-legitimizing, utilitarian logic that objectified nature and the environment as raw materials, that are ‘just out there’, only waiting to be extracted, monetized or mined (2019b, p. 4). It’s this shift from the appropriation of natural to social resources that, for Couldry and Mejias, characterizes the colonial moment of contemporary data capitalism (2019b, p. 10). It ushers in a new regime of dispossession and enclosure that leaves no part of human life, no layer of experience, that is not extractable for economic value (2019b, p. 3; 2019c). This produces the social for capital under the pretext of advancing scientific knowledge, rationalizing management or personalizing marketing and services (2019c).

Couldry and Mejias emphasis on the expansion of dispossession from natural to social resources begs for a closer examination, for it implies an inherent split between the social and the natural as ontologically distinct categories of social existence, that may end up reifying the very structures of coloniality they seek to confront. Or, to put it differently, there is a need to better situate data within ontologies of the social if we are to fully understand who or what is dispossessed in data and in the name of whom or what. Such a self-reflexive task only becomes meaningful if conducted in historically and geographically specific contexts, to avoid losing sight of the differential effects that distinguish the beneficiaries of historical forms of colonialism from those who continue to struggle against its impact and consequence. Such a situated analysis also helps to emphasize the intersectionality of violence of dispossession and displacement in data relations and to draw a clear distinction between settler colonialism and other modes of colonisation, both of which are the main focus of my own research (2019 forthcoming, 2019, 2016).

Colonialism, after all, is not a fixed, universal structure, much less a coherent vector of power or rule. Colonialism operates through multiple forms of domination – military, economic, religious, cultural and onto-epistemic – each with its own legitimation narratives and tactics, rhetorical maneuvers and trajectories. What unites them into a shared set of characteristics, in my view, are the ways they contributed to the projection of modern, European knowledge onto the rest of the planet, such that other ways of knowing and being in the world were delegitimated and disavowed.

Modern European knowledge, as decolonial theory remind us, was firmly grounded in Cartesian dualisms that divided the world into two separate independent realms – body and mind, thinking and non-thinking substance – from which a whole range of other binaries i.e.: nature and society, subjects and objects of knowledge, human and non-human could be inferred (Braidotti, 2016; Maldonado-Torres, 2007; Mbebe, 2017; Quijano, 2007). Taken together they provided the normative horizon for managing social and spatial relations throughout the modern colonial period and that laid out the central parameters around which ethico-political subjectivities could be forged.

In part two: early Palestinian datafication practices demonstrate the violence of Cartesian thinking as a case of reimagining data agency. Read it here.

About Monika Halkort

Monika Halkort is Assistant Professor of Digital Media and Social Communication at the Lebanese American University in Beirut. Her work traverses the fields of feminist STS, political ecology and post-humanist thinking to unpack the intersectional dynamics of racialization, de-humanisation and enclosure in contemporary data regimes. Her most recent project looks at the new patterns of bio-legitimacy that emerge from the ever denser convergence of social, biological and machine intelligence in environmental sensing and Earth Observation. Taking the Mediterranean sea as her prime example she unpacks how conflicting models of risk and premature death in data recalibrate ‘zones of being’ and ‘non-being’ (Fanon), opening up new platforms of oppression, alienation and ontological displacement that have been characteristic of modern coloniality.

References

Braidotti, Rosi. (2016). Posthuman Critical Theory. In D. Banerji, M. R. Paranjape (eds.), Critical Posthumanism and Planetary Futures (pp. 13–32). e-book: Springer India. doi: 10.1007/978-81-322-3637-5

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019a). The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019b). Data Colonialism: Rethinking Big Data’s Relation to the Contemporary Subject. Television and New Media, 1 -14.

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. (2019c). The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Retrieved March 25, 2019, from Colonised by Data: https://colonizedbydata.com/

Halkort, M. (forthcoming) ‘Dying in the Technosphere. An intersectional analysis of Migration Crisis Maps’, in Specht, D. Mapping Crisis, London Consortium for Human Rights, University of London, London, UK

Halkort, M. (2019). Decolonizing Data Relations: On the moral economy of Data Sharing in a Palestinian Refugee Camp. Canadian Journal of Communication , 317-329.

Halkort, M. (2016) ‘Liquefying Social Capital. The Bio-politics of Digital Circulation in a Palestinian Refugee Camp’, in Tecnoscienza, Nr. 13, 7(2)

Maldonado-Torres, N. (2007). On the coloniality of being: contributions to the development of a concept. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 240-270.

Mbebe, A. (2017). Critique of Black Reason. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

McRae, Andrew. (1993). To know one’s own: Estate surveying and the representation of the land in early modern England. The Huntington Library Quarterly, 56(4), 333–57. doi: 10.2307/3817581

Mignolo, W. (2009). Coloniality: The darker side of modernity. In S. Breitwieser (Hrsg.), Modernologies. Contemporary artists researching modernity and modernism (S. 39 – 49). Barcelona: MACBA.

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2-3), 168-178.