This article addresses the importance of WhatsApp during COVID-19 times in Argentina. It analyzes the use of WhatsApp amidst informal and institutional actors and the bridges it has built for interacting, communicating and creating communitarianism.

by Raquel Tarullo*

Circles of friends, members of sports clubs, parents associations and work colleagues are new actors that have come along with the pandemic in Argentina to provide, in the emergency, food and clothing for thousands of families who live in poverty. These groups, that are neither social movements nor civic associations, use their WhatsApp contacts and the groups they have on this social network to promote, by using distribution lists, their food drives to prepare meals they deliver once a week.

Parallel to this trend, teachers of schools with vulnerable student bodies find in WhatsApp the channel for communicating with families and, in some way, accompanying students in what the government has called ‘Pedagogical Continuity Plan’, as most of them do not have access to the internet or technological devices. Moreover, teachers use this platform for sharing useful information with these families, such as state assistance payment calendars and the WhatsApp direct line for reporting gender or familiar violence.

A universal platform

In Argentina, WhatsApp has become the best ally for an activism that has introduced new actors and new practices since national government established a severe lockdown on 20 March. This platform is used by groups of people that have organized themselves to prepare meals for those poor families that COVID-19 has enormously hurt. Besides, WhatsApp is the only channel that teachers of schools with vulnerable student bodies have not only for interacting with their students’ families, but also for being a communication bridge between the government and their students’ families. Why do they both use WhatsApp? Because the use of this platform in Argentina is almost universal: more than 90 percent of the population use this channel to stay connected and communicate, sharing statuses, selling goods and spreading news. Currently, it is also used for performing micro repertoires of activism.

More than a half of kids and teenagers live below the poverty line in Argentina. According to the last UNICEF report of COVID-19 effects in the country, that percentage will reach 58 percent by the end of this year. Even though the national government has taken socioeconomic measures to maintain the situation under control, such as the Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia (Emergency Household Income), a state assistance for poor families, and zero interest rate loans for the self-employed with minimum or low income, the great majority of Argentines has been suffering a series of crisis that in recent years have widened gaps greatly.

One half of the country’s workforce get about in an informal economy, working under the table and surviving on changas(occasional one-day job that allows for minimal daily sustenance). Besides, cartoneros/as, who live from the sales of disposed garbage items, are part of this vulnerable group. This segment is the most affected because of the direct and indirect effects of the pandemic. Moreover, social movements and civil associations with a strong identity and established history that work in slums and the most helpless zones of the country have warned that people from the most vulnerable urban areas are the most affected by the COVID-19 contagion. In relation to this, La Garganta Poderosa, an NGO that has representation in many countries of Latin America, launched last week a social media campaign #contagiásolidaridad (#infectsolidarity) to promote a collective awareness of the situation.

A diffusional space for the urgency

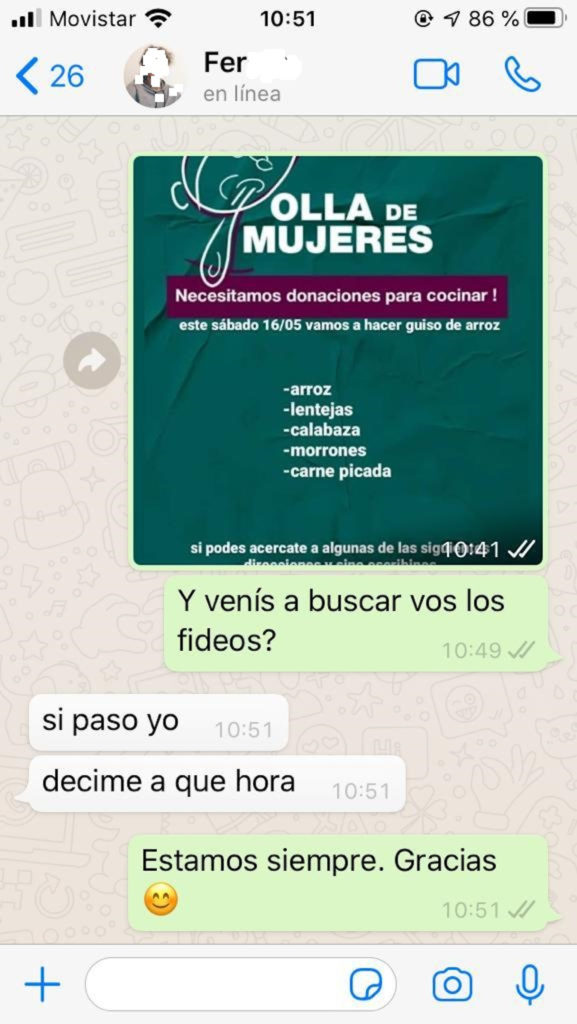

Olla de Mujeres (Saucepan of women) is a group formed by five girls. Only two of them knew each other before. They decided to come together after exchanging some messages through WhatsApp, and they used this channel for organizing themselves. Since April, they have been using this channel to post in their statuses a flyer with the information about the goods they need for preparing meals, along with their WhatsApp numbers. As they are very active and social, they have many WhatsApp groups, in which they share this information. The members of these groups replicate this message, building an informal network of solidarity. They receive messages from unknown people, offering supplies and help. As they have a special permit issued by the authorities and required to drive around during lockdown, they collect donations all around the city. An NGO lends them its kitchen facilities for cooking. Every Saturday, they distribute the meals to a hundred families.

Fernando is 22 years old, has many friends and many groups of friends in WhatsApp. He uses these contacts for food drives. He creates WhatsApp broadcast lists and his parents do the same, helping him to promote his campaign of food donations. Fernando and his lifelong friends cook every Saturday in the kitchen of the club where he plays volleyball. Last Saturday, they distributed more than 200 meals to people who went to a merendero, or food bank for low-income population.

School teachers have a fundamental place in this network, diffusions and emergencies. Schools are one of the institutions that have deeply transformed themselves to adapt to the current situation.

Some extra data to understand the situation: the majority of the schools that are settled in popular and deprived areas of the country offer breakfast, lunch and/or afternoon snacks to their students living in vulnerable conditions. However, since on-site classes were suspended, teachers are in charge of delivering every other week a bag of food products, a measure that the national government has introduced to replace school meals and increase social assistance to these families. Along with the food provisions, teachers distribute school booklets for students to continue with their education, in order to guarantee the Pedagogical Continuity Plan. Then, communication continues via WhatsApp. “Far from other schools that can work via Google Classroom, Zoom or other platforms, our unique way of communication with families and students is via WhatsApp. In our community, families do not have neither internet access nor computers. We give them these booklets, and then we try to continue communication using WhatsApp,” says Jéssica, head of a school in the province of Buenos Aires.

However, the content of these booklets has received much criticism: the Mapuche’s Confederation (the NGO that congregates native people settled in the south of the country) reported that they were described as a vanished community, using discriminatory vocabulary, said the report. The National Ministry of Education publicly apologized to the community.

Even though browsing the governmental site educ.ar – where students and/or their parents can download these booklets – is free of charge and contents can be downloaded without consuming mobile data, access is almost impossible for families with many kids and only one mobile phone per household. “Besides, most of these parents haven´t finished their primary studies. Even if they had mobiles or computers, they wouldn’t have the digital skills for accessing to these sites and downloading the pedagogical material”, says Valeria, a social worker who uses WhatsApp to help women of impoverished communities sending them information about State health assistance for them and their kids.

Nevertheless, communication via WhatsApp largely exceeds pedagogical goals. “At the beginning, it was for school purposes, but currently we use it to share useful information that runs in other social media, such as Facebook and Instagram, which families of our school may not have access to”, explains Jéssica. So in this group formed by teachers and families, schools share information about those places where they can go for free food during the weekends (where Fernando and his friends, Olla de Mujeres and many other groups deliver meals every weekend), state assistance payment calendars and dates of food bags delivery. “We are the link between families and government”. For instance, new of a WhatsApp direct line for reporting gender and domestic violence that was launched recently by the government were shared by teachers using these WhatsApp groups.

However, it is not easy. Jéssica explains that the onsite meetings every 15 days – during which they deliver food bags – are also used for collecting data about connectivity and communication devices available to their students, in order to improve their ways of interacting with students and families and adapt practices in which the dynamics of the context is adverse for the community of the school she heads. “Seventy percent of families have prepaid mobile cards. They top-up their phones when they receive State assistance. That lasts around 10 days. Then communication is cut off.”

The pandemic in Argentina has revealed repertoires, dynamics and resistances of a ‘backstage activism’ that has WhatsApp as a main ally: for creating networks, for organizing solidarities, for coming along with kids in their educational continuity, for spreading information that is originated in other online spaces to which families of these vulnerable communities don’t have access, for reporting and asking for help. All of these are micro practices of an activism that has become different, but seemingly not less effective, during COVID-19 times. However, it is important to say that these creative uses are responses that different actors perform for collaborating with humble communities during this emergency, an emergency that has made visible more than ever before different edges of a context where resources are unequally distributed.

About the author

Raquel Tarullo. PhD in Social Sciences and Humanities. Lecturer and Researcher at National University of the Northwest of Buenos Aires Province (UNNOBA) and National University of San Antonio de Areco (UNSAdA). Visiting Research Fellow, Sociology Department, Goldsmiths, University of London (2019-2020). Contact: raqueltarullo@gmail.com/@unflordeviaje