by Miren Gutierrez

Is the so-called South more creative when it comes to devising bottom-up, data-based solutions for social needs? Looking at Luis Hernando Aguilar’s experience in disaster response, it might seem as if the answer is affirmative. Indeed, the South—understood as a space for resistance, ingenuity and alternative—has been the geographic and intellectual birthplace of digital humanitarianism, which I consider a form of proactive data activism, that is to say the series of sociotechnical practices of engagement with data infrastructure that use, produce or appropriate data for social change (Milan and Gutierrez 2015).

Aguilar, a Colombian currently based in Amman, is a pioneer ‘digital humanitarian,’ a new figure in the international response to disasters, crises and armed conflicts. He is the Information Management Officer for the Whole of Syria Health Cluster at the World Health Organisation (WHO) based in Amman, and has held similar positions at the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER) and at the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), based in Ghana (covering Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leona as well) and Colombia. In these positions, Aguilar has specialized in creating information systems to support those assisting people affected by complex emergencies, and to liaise volunteers, victims and humanitarians, so they meet, cooperate and coordinate action. I have had the opportunity to interview him several times over the past couple of years to discuss how digital humanitarianism looks like from nearby. In this blog post, I share some insights from these precious conversations.

Digital humanitarianism uses spatial, communication and data infrastructures to aid humanitarian efforts in quasi-real time, a significant paradigm change. Utilizing crowdsourced data gathered via different channels, verifying the data and visualizing the resulting analysis through interactive mapping software, digital humanitarianism has disrupted traditional emergency operations, happening in a more hierarchical, fixed and deliberate manner. Aguilar considers 2010 as the year when everything changed.

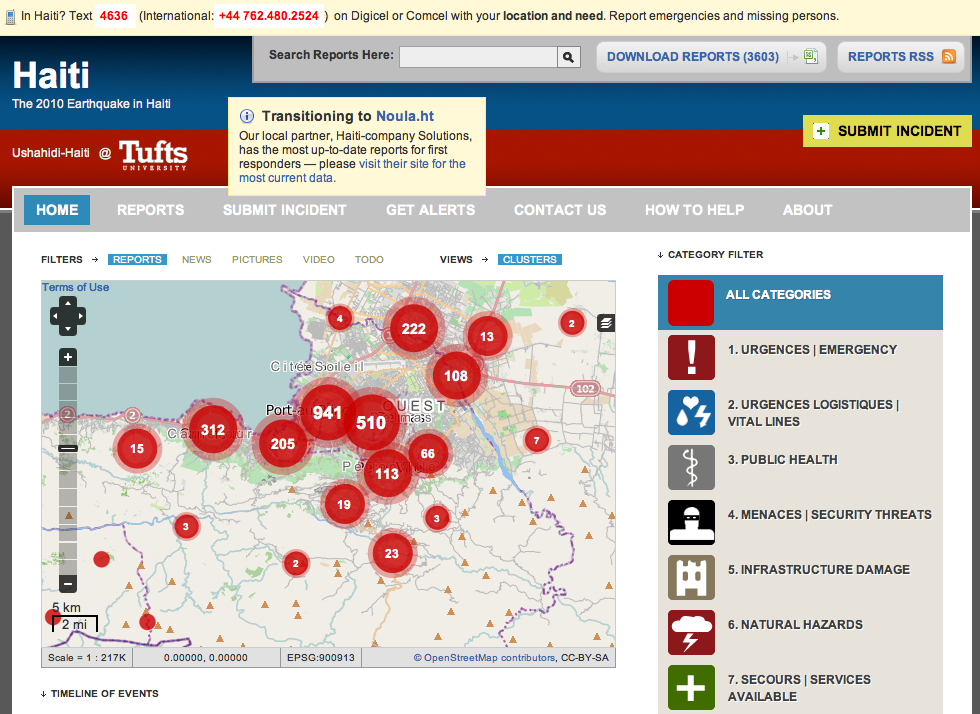

On January 12, at 16:53:09 local time, an earthquake hit Haiti. Within minutes, a group of digital humanitarians—supported by the Haitian diaspora in the US—deployed the Ushahidi platform to gather reports coming from victims and witnesses. “It was chaotic: No transportation, the lines of communication were broken. [Against the odds], thousands of eyewitness accounts submitted through email, text or Twitter, mostly sent via phones, were analyzed and made visible, and the [Ushahidi] platform started being used to coordinate disaster relief operations,” he says.

Hundreds of volunteers from everywhere handled reports of entrapped people, medical emergencies and requests for help, feeding the map so rescue workers could use the information on the ground. A total of 1,500 reports were gathered and visualized in the first two weeks alone.

“The Ushahidi Haiti Project, although far from perfect, marked a paradigm shift that meant the incorporation of citizen data into the running of humanitarian operations,” Aguilar says.

A parenthetical comment is in order here: Links in this commentary take you to Ushahidi blogs, which sometimes include static maps. Unfortunately, digital humanitarianism is ephemeral, and so are its maps. I say “unfortunately” because, as a researcher, you are forced to seize the moment and observe these maps as they develop. Then, they often vanish. They are living things, perennial works in progress, never to be whole. The transient nature of many of these activities has to do with two components: a) their humanitarian nature, and b) their dependence on user crowds and digital humanitarians. Humanitarianism refers to the short-term efforts involved in providing material and logistic assistance, and responding to crises, mediating in conflicts and undertaking peacekeeping operations. In general, humanitarian organizations get in and out quickly with the objective of saving lives and increasingly also livelihoods. They deal with the emergency, not its underlying causes. On the other hand, crisis-mapping, crowd-sourced data platforms depend totally on the action of crowds and digital humanitarians. Without their enthusiastic engagement, there is only an empty map. “Volunteers have to be managed too. During the first three days, everybody wants to help, but many times the emergency situation lasts for months,” explains Aguilar.

With the rise of the data infrastructure and other information and communication technologies, Aguilar has been progressively implicated in major crises, such as the earthquakes in Haiti and Chile (2010), and Ecuador (2016), the crisis mapping in Colombia and Libya, the Typhoon Haiyan mapping in the Philippines (2013), the Ebola emergency in West Africa (2014-2016) and the crisis in Syria.

Since then, the Haiti crisis mapping, Ushahidi—“testimony” in Swahili—and other crowd-sourced data-based crisis mapping platforms have been launched to tackle emergencies across the world. And in 2012, the Digital Humanitarian Network –a network-of-networks— was launched by Patrick Meier and Andrej Verity to link volunteer and technical communities with humanitarian organizations.

The Ushahidi Haiti Project was later the basis for the creation of the Standby Task Force (SBTF) in 2010, an independent mapping community of trained volunteers who are permanently prepared to get involved in a crisis before a more significant team of relief workers could assemble. The SBTF was first tested a month later in a drill exercise of an earthquake affecting Bogota, in which Aguilar was involved. He was also instrumental in making OCHA the first UN agency to use Ushahidi in the crisis mapping of Libya in 2011 because traditional humanitarian organizations did not have access to the country.

Ushahidi is an excellent example of “infrastructuring” in the Global South. Most names and cases mentioned by Aguilar in our conversations come from the South. Ushahidi was created in Kenya in 2008, during the post-electoral violence, the SBTF was first tested in Colombia, and Libya was the UN’s first experiment with crisis mapping based on crowd-sourced data.

“I believe that the lack of resources and need improve creativity. There are plenty of capacities in developing, so-called Southern countries; but there are plenty of people in rich countries who collaborate in humanitarian operations too,” says Aguilar. What is important is that digital humanitarians, conventional rescue teams, as well as victims and witnesses—he adds—can now work together and react more quickly in the face of disaster thanks to data, information and communication infrastructures.

Many deployments of the Ushahidi platform have failed too for lack of crowds to sustain them or for glitches in the verification systems, for example. However, the impact of these platforms has signified a point of no return for international humanitarianism for their ability to quicken and enhance rescue operations.

The Ushahidi platform and crisis mapping at large have become the means of more disruptions. Data infrastructure—including the datasets, software and storage needed to clean, analyze, store and visualize data—mostly comes from the so-called North, which often determines how data are obtained, interpreted and even used, because neither data nor their infrastructure are neutral. Meanwhile, Ushahidi, although based on existing technologies, is a product of the African ingenuity. And it has been so successful that it has been embraced outside the boundaries of crises and the geographic South (i.e. Snowmageddon, mapping snowball fights in New York and Boston in 2010), influencing people’s relationship with maps beyond humanitarianism.

The Ushahidi Haiti Project marked the beginning of a great, Southern adventure. In 2010, something magic happened: the birth of digital humanitarianism, “a marriage of technology and data with people’s solidarity,” concludes Aguilar.

*This is a summary of several interviews which have been combined and will appear as one soon—stay tuned! The interview draws on my PhD dissertation “Bits and Atoms: Proactive data activism and social change from a critical theory perspective”, defended in June 2017 and soon forthcoming in a shareable format, which relies on thirty semi-structured interviews with experts, data activists and data journalists, as well as several in-depth interviews and a case study, focused on the Ushahidi platform.

About the author. Dr Miren Gutierrez is the Director of the postgraduate programme “Data analysis, research and communication” and a lecturer of Communication Sciences and Media at the University of Deusto, Spain. She is a Research Associate with DATACTIVE as well as the Overseas Development Institute, London. Miren’s main interest is data activism, or how data infrastructure can be utilized for social change in development, climate change and environmental issues. She holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.

About the author. Dr Miren Gutierrez is the Director of the postgraduate programme “Data analysis, research and communication” and a lecturer of Communication Sciences and Media at the University of Deusto, Spain. She is a Research Associate with DATACTIVE as well as the Overseas Development Institute, London. Miren’s main interest is data activism, or how data infrastructure can be utilized for social change in development, climate change and environmental issues. She holds a PhD in Communication Sciences.