Author: Miren Gutiérrez

As we grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, another crisis looms over our future: overfishing. Fishing fleets and unsustainable practices have been emptying the oceans of fish and filling them with plastic. Although other countries are also responsible for overfishing, China has a greater responsibility. Why is looking at the Chinese fleet important? China has almost 17.00 vessels capable of distant water fishing, as reveals for the first time an investigative report published by Overseas Development Insitute, Londres.

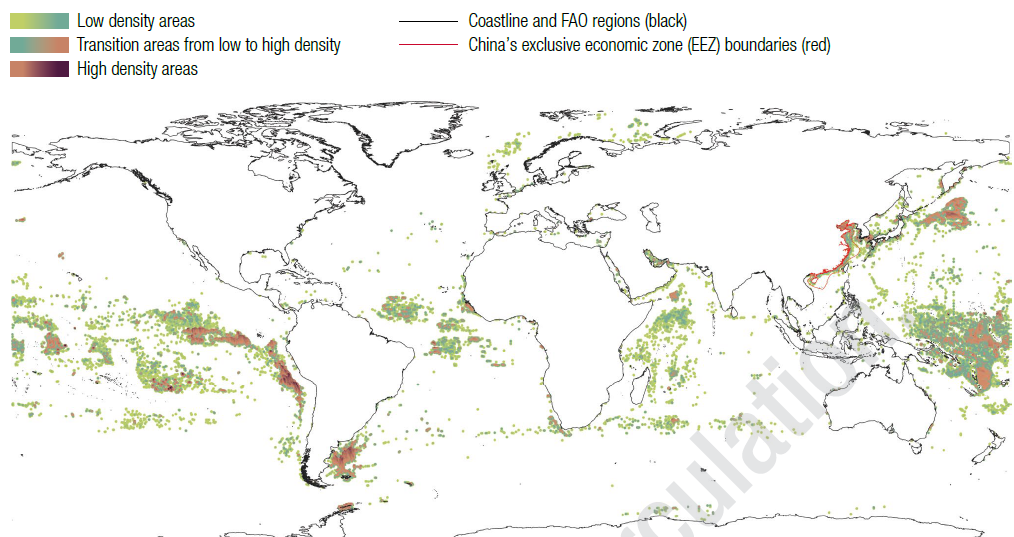

As part of a team of researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, London, I had access to the world’s largest database of fishing vessels. Combining these data with satellite data from the automatic identification system –which indicates their movements—, we were able to observe their behaviour for two years (2017 and 2018). To do this, we employed big data analytical techniques, machine learning algorithms, and geographic information systems to describe the fleet and analyze how it behaved.

And the first thing we noticed is that China’s fishing fleet is five to eight times larger than any previous estimation. We identified a total of 16,966 Chinese fishing vessels able to fish in “distant waters”, that is, outside its exclusive economic zone, including some 12,500 vessels observed outside Chinese waters during the same period.

Why is this important? If China’s DWF fleet is 5-8 times larger than previous estimates, its impacts are inevitably more significant than previously estimated. This is important for two reasons. First, because millions of people in coastal areas of developing countries depend on fishery resources for their subsistence and food security. Second, due to this extraordinary increase, it is difficult to monitor and control fishing activities in distant waters of China.

The other thing that we observe is the most frequent type of fishing vessel is the trawler. Most of these Chinese trawlers can practice bottom trawling, which is the most damaging fishing technique available. We identified some 1,800 Chinese trawlers, which are more than double what was previously thought.

Furthermore, only 148 Chinese ships were registered in countries commonly regarded as flags of convenience. This shows that the incentives to adopt flags of convenience are few given the relatively lax regulation of the Chinese authorities.

Finally, of the nearly 1,000 registered vessels outside of China, more than half have African flags, especially in west Africa, where law enforcement is limited and fishing rights are often limited to registered vessels in the country, which explains why these Chinese ships have adopted local flags.

What can be said about the ownership of these fishing vessels? It is very complex. We analyzed a subsample of approximately 6,100 vessels to discover that only eight companies owned or operated more than 50 vessels each. That is, there are very few large Chinese fishing companies since small or medium-sized companies own most of them. However, this is only a facade, as many of these companies appear to be subsidiaries of larger corporations, suggesting some form of more centralized control. The lack of transparency hampers monitoring efforts and attempts to hold those responsible for malpractice accountable.

But another exciting facet of the ownership structure is that half of the 183 vessels suspected of involvement in illegal, unreported or unregulated fishing are owned by a handful of companies, and also that several of them are parastatal. This means that focusing on them could solve many problems because these companies own other ships.

There has been an extraordinary boom in Chinese fishing activities that is difficult to control. Chinese companies are free to operate and negotiate their access to fisheries in coastal states of developing countries without being monitored, especially in West Africa. This laxity contrasts with the policy of the European Union to reduce its fishing fleet and exercise greater control over its global operations.

This report is a data activist project that aims at redressing the unfair situation for nations, especially in west Africa, that cannot monitor and police their waters.

This is a version of an op-ed published in Spanish by eldiario.es.

About the author: Miren Gutiérrez is passionate about human rights, journalism and the environment (with a weakness for fish), and optimistic about what can be done with data-based research, knowledge and communication. Prof. at the University of Deusto and Research Associate at the Overseas Development Institute. Miren is Research Associate @DATACTIVE.