What does datafication mean for social movement formation and work under the current crisis situation in Brazil? This article examines the Vidas Negras Importam (Black Lives Matter) emerging movement in Brazil, and the conditionings imposed on it by datafied surveillance systems.

By Simone da Silva Ribeiro Gomes

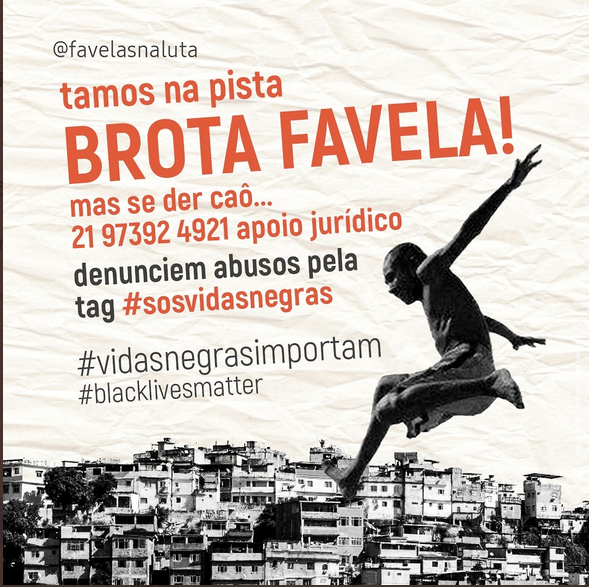

This article conveys reflections on one aspect of the datafied society: how police violence in plural Global Souths – not limited to the geographical connotation of the concept – shape protest dynamics, with the example of recent manifestations in Brazil. Context is provided by the black, favela, and periphery residents marching through Rio de Janeiro on June 7, in the #VidasNegrasImportam (#BlackLivesMatter) protest against racism. For the second Sunday in a row, the streets throughout Brazil were filled by protest for Black Lives, motivated by protests in the US for George Floyd springing up in late May. The protesters marched in opposition to the State’s policies, in relation to the intensification of social vulnerability amid the country’s COVID-19 triggered economic and public health crisis as well as the unceasing police violence in the favelas during the coronavirus pandemic.

Rio de Janeiro´s Military Police also conveyed orientations in their Twitter account, asking protestors on their way to the march not to bring hand sanitizer in quantities larger than 50ml.

In a city where 80% of people killed by police in the first half of 2019 were black, and state violence only keeps increasing in the favelas, in the midst of the pandemic, protests were called in response to the murder of Matheus Oliveira, a young black favela resident shot by the police while he was returning home. Between January and June 2020, police in the state of Rio de Janeiro killed 881 people, about five per day, a significant increase on the last few years, for instance in 2018 1,534 people were killed by police officers.

That way, black, poor, favela, and periphery youth filled downtown Rio de Janeiro´s main avenue, marching despite rumors of police repression on social media and criticism questioning the merits of risking COVID-19 infection for an in-person protest in the streets. The police frisked protestors on their way to the march in pick-up trucks and on motorcycles, on horseback and on foot, police wielded batons, rubber-bullet rifles, and gas cannons, intimidating protestors. But the dynamics that unfolded include the information on hand sanitizer by police themselves, with emblematic consequences since there is no municipal or state-level decree restricting the quantity of hand sanitizer one can carry for personal use. What police forces do is also to use this as justification to detain protesters on their way out of the protest. Police forces then, in Brazil, but also in Mexico and other Latin-American countries have securitized protests in order to criminalize dissent and the dynamics of social movements in those contexts differ from the North, where resistance does not frequently face “hard” techniques of repression: preemptive arrests, surveillance, riot police, arrests, prosecution, and incarceration.

Even if studies reveal that digital monitoring may have a dampening effect on police use of force, videos of excessive force show the persistence of violations (Harcourt, 2015). Still, surveillance concerns pose different threats for southern black poor favela protestors in the Global South, even if the growing state security apparatus to control and repress protests is worrisome all around the world, frequently made possible by drones, crescently used to monitor, repress and eliminate targets.

Nonetheless, protesters in Brazil echo police warnings to avoid further trouble. People who could not be on the streets – due to pandemics – were asked to share activist´s posts and give visibility to their actions. Those highly aired information in recent protests are enlightening of some of the consequences of datafication in collective action. The paradigm change able to transform “social movement society” here urges scholars to reflect on how it intersects with known protest dynamics, my intention is to share reflections on how movements will be organized while the pandemics last. This reflection is shared to unveil some nuances of protesting in pandemic times in police violence related contexts and cop watching is a trademark of violence related contexts. It increasingly takes place in Brazil and other contexts of the Global South.

That way, Brazil has seen the proliferation of digital technologies originally attributed to state and company surveillance to protest countersue, as a way to protect themselves and protest innovations are more evident with populations where State abuse is more frequent. The impact of COVID-19 on the Souths here has to do with both surveillance and grassroots efforts to counter narratives of long time negotiations between protestors and police forces, specially young, poor, black favela residents, that are daily surveilled and disrespected in their houses, but also develop counter-surveillance strategies to tackle police abuse, as large scale Cop watching.

What strikes as unprecedented in Global North outside racial protests, but seem ubiquitous in Brazil is police violence. An overall view of orientations for protesters in pandemic times, made in the US, for example, do not consider what was mentioned above. However, if global activists have a history in the 20th century of self entitled “police accountability”, they somehow turned from more communal, organized, intentional documentation of police to more individualized, incidental documentation by independent protesters. There is an extensive literature on cop watch and surveillance in the last few years. In Brazil, massive protests in June 2013 are among the visible origins of more intensive and rationalized Cop Watching.

Some challenges for future protests in the Global South are highlighted in how they originally rely on the logic of numbers, how can the relevance of these movements is affected by the prohibition of big gatherings, since they cannot proceed with their usual repertoires of protest. Also, as mass media have played an important part in disseminating on/about social movements and technologies have reinforced some monopolies in this pandemic period, we must turn visible alternative uses of counter-stream technologies, such as one-a-one police accountability Cop Watching.

Nonetheless, activism is also working on those terms, aside from protesting to end violent policing, there are civil initiatives fighting the government’s use of harmful face surveillance technology, for instance. Later this month two major vendors of face surveillance technology – Amazon and IBM – announced that in light of recent protests against police brutality and racial injustice, they would pause or end their sale of this technology to police. The movement to ban face recognition is increasing as recent protests have shown their strength in fighting tech companies enable and profit off of a system of a racist surveillance and policing.

It is no wonder in Brazil that Optical Character Recognition – OC have been widely supported by the federal government and recently implemented in some states, showing flaws that increased the mass incarceration of young, black favela habitants. The same ones that know how data insensibility policies are dire for them, as 90,5% of incarcerated by facial monitoring in Brazil are Black. It is no wonder then how not only surveillance seems to work differently in global North and South, with more police violence in the second case and Cop Watching has come to stay. Counter-surveillance then, must be taken into account how social control of movements works, not just repressing activists, but the terrain upon which they operate and the most immediate struggles they must transform in order to succeed.

This article briefly analyzed the rise of securitization of protests by Latin-American to criminalize dissent. I have stated how the dynamics of southern movements – with similar causes, such as racism – differ substantively from the Global North. In this context, Brazilian Military Police is highlighted as its “hard” techniques of repression have gained attention in the shift of its deployiment of force on black, poor, favela youth outside their houses, but on the streets, protesting against racism. In the last few months, strategies of counter-surveillance collective such as Cop Watching have gained relevance in social movements that fight human rights abuse. Some challenges for the future include how activists will cope with the consequences of datafication and violence in collective action. We will see.

About the author

Simone da Silva Ribeiro Gomes is an Assistant Professor of Social Sciences at Universidade Federal de Pelotas (UFPel), in Pelotas-RS, Brazil. Simone can be found on Twitter @sims_zg.