By Guillén Torres

(Image copyright: Bob Mankoff)

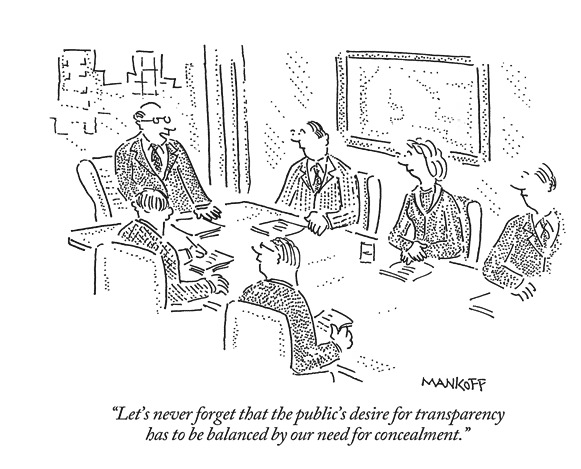

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) in July, 2016, ProPublica, a U.S. nonprofit newsroom, published a long essay titled Delayed, Denied, Dismissed: Failures on the FOIA Front, in which several journalists detailed their frustrating experiences when requesting government data from U.S. institutions. In the comments section of ProPublica’s website, a reader captured the general feeling of the article as follows:

“To summarize: byzantine internal processes governed by antiquated laws operate with insufficient resources and no sense of urgency or accountability, and are shepherded by sometimes incompetent or dishonest public servants to produce documents that often have self-serving redactions or outright denials (sic)”.

This grim picture of the U.S. Government’s openness -with recent concerns related not only to Trump, but also Obama– is not an isolated case, unfortunately. Around the world, other governments have been accused by journalists and activists of discursively pushing openness forward, despite effectively making the use of government data difficult. For example, the Mexican government takes pride in having one of the most advanced transparency legislations, yet is currently discussing a new General Archives Law that will leave in the discretional and unaccountable hands of the Ministry of Interior the decision of what information should be preserved, and hence what data exists to be accessed. Moreover, the federal government is still struggling to make a buggy National Transparency Platform work, almost a year after it was presented as the main tool to guarantee Mexican citizens’ right to information. In the opposite side of the world, India’s recent public consultation to draft its License for Open Data use ended with a blatant disregard of the advice given by citizens, producing a regulation that does not offer any warranty against errors or omissions in the data held by the government, and transfers the liability for misuse to the citizens (instead of the data controller).

These examples point to the existence of a reactive process to citizen empowerment, in which some governments have found institutional ways to resist civil society’s access to data, hindering its ability to influence political processes. The research I will be conducting within the DATACTIVE project aims to locate empirically and frame theoretically this institutional reaction to citizen empowerment, to describe how it influences the configuration of the power relation between the State and citizens, and more broadly, how it affects the practice of data activism. To do so, I will start with a question originating in my own experience as an activist in Mexico: what if institutional resistance to public use of data is a political strategy, instead of the result of non-political flaws in the regulation related to Government Data?

By not taking for granted the State’s compromise to openness, I will explore whether the sociomaterial practices related to the production, dissemination and use of Government Data might make possible not only the empowerment of citizens, but also the State’s monopoly over some political issues which, according to the ideals of modern democracy, should be subject of collective discussion. The point of departure will be the work of proactive data activists who, while looking to mobilise Government Data to strengthen their attempts to influence public policy or oversee governmental action, have struggled to get the information they seek. In a second stage, I will look at how institutional actors deploy their resistance strategies, tracing the regulatory and material components involved in the process. Finally, I will develop a similar analysis over the strategies used by activists to counter institutional resistance. In the process, I hope to contribute to the study of the role played by data in configuring the power relation between citizens and the State in the age of Open Government, as well as helping to identify (and ideally produce) formal and informal mechanisms that activists can implement to keep rogue institutions under citizen control.

I am always interested in hearing about instances where public institutions do not follow through on their claims of making data effectively open and accessible to interested activists. If you have any examples or experiences, please drop me a line: guillen@data-activism.net